The story behind Robert Capa’s iconic shot of a soldier in the surf at Normandy, one of the most celebrated pictures of the Second World War, is nearly as complex as it is incredible. In 1944, Capa, later a co-founder of the photography collective Magnum, was assigned to cover the Allied invasion of Normandy by LIFE picture editor John G. Morris. Capa, then 30 years old, was one of only 18 American photographers given credentials from the U.S. Armed Forces to cover the preparation for the invasion, and one of only four credentialed to land on the beaches of Normandy alongside American troops.

Dropped nearly 100 yards from the beach during the first wave of the invasion, Capa waded through waist-deep water dodging heavy fire and carrying three cameras. He managed through careful maneuvering to make it to land, where he alternated between taking cover and making pictures as troops made the same deadly journey to shore. In the 90 minutes that he spent on the beach, Capa witnessed men shot, blown up and set on fire all around him.

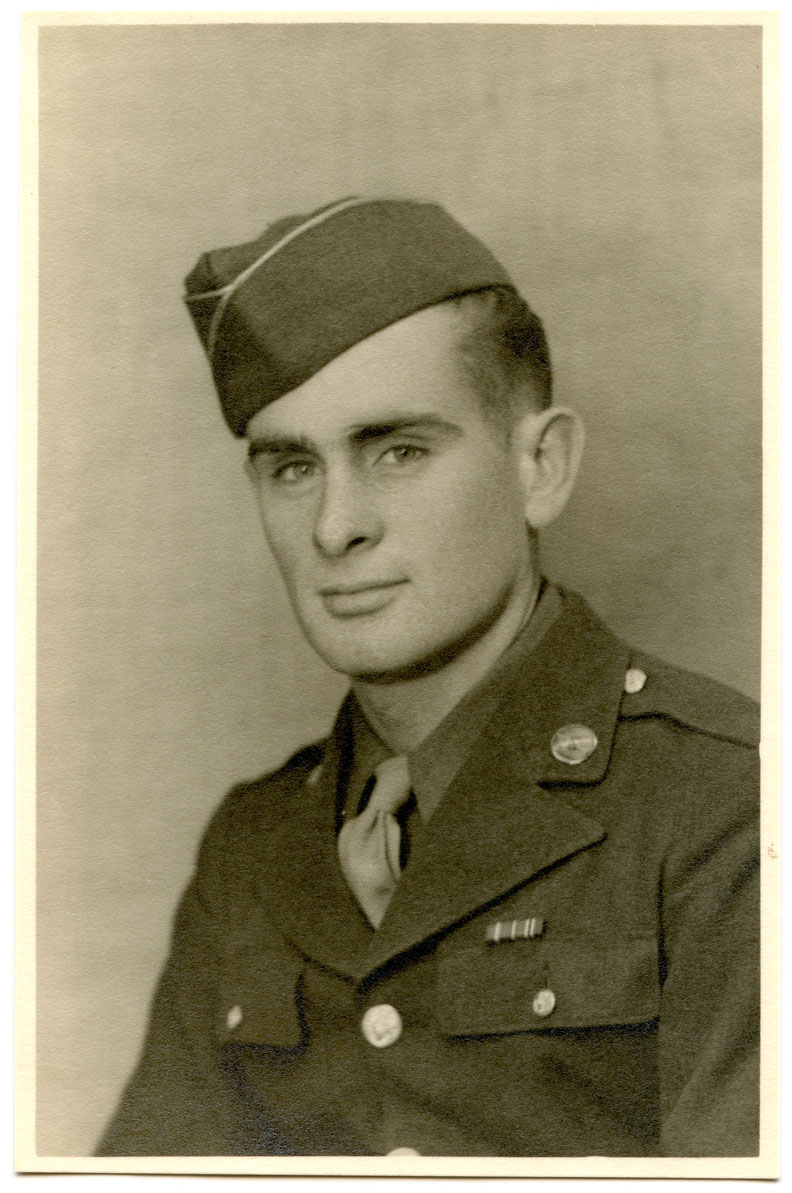

At nearly the same time, a young GI, now known to be Huston Riley, disembarked from his landing craft into water over his head — and sank straight to the bottom, weighed down by his gear. Riley activated his flotation device and quickly became a sitting duck for German machine gun fire as he bobbed on the surface. Over the course of 30 minutes, Riley made his way to shore while bullets ricocheted off his shoes and pack. Just as he hit land and began to run, Riley caught four bullets in his right shoulder, two of which stayed lodged in his body. Two men quickly came and helped him reach cover, one of whom, Riley later recalled, had a camera around his neck. The photographer was Capa, and somewhere between the moment when Riley reached the surf and when he was being lifted, wounded, out of the water, Capa made the photo that for generations has defined the chaos and the courage witnessed on D-Day.

The journey of Capa’s film that followed, explained in detail in the video above by Capa’s editor and longtime friend, John G. Morris, was almost equally as perilous. Capa’s film survived only because he carried it off the beach himself. His colleague Bob Landry’s film, along with the film of nine other photographers and cinematographers, was lost, having been handed off to a colonel who dropped the whole pack in the ocean while boarding a transport ship. And although Capa shot approximately 106 frames on the beach, only a handful have survived. Though the exact number of surviving frames is uncertain, the actual negative of the picture known as The Face in the Surf, along with another from the set, was lost sometime after the photo’s publication in the June 19, 1944 issue of LIFE. It is, in a sense, a testament to the incalculable hardship and violence of the Longest Day that the only surviving photographic record of the Omaha Beach landing from the beach itself are nine hard-won, fragile, immensely powerful negatives.

Editor’s note: This video has been updated to include a photo illustration credit.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com