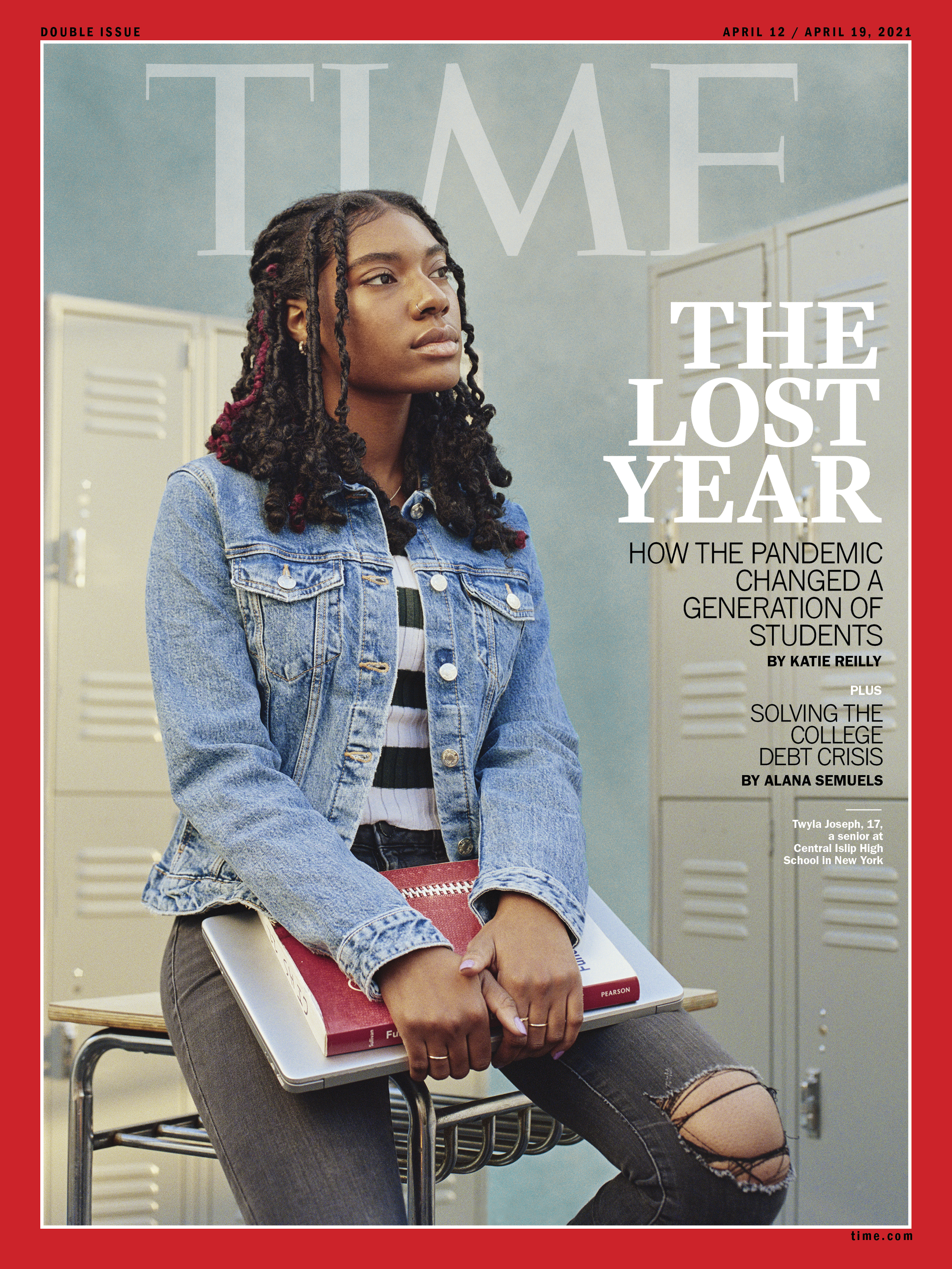

The first sign that Twyla Joseph’s college application process was not going to go as planned came on March 13, 2020, when, a day before her scheduled SAT, she learned the test had been canceled. The May and June tests were also canceled as coronavirus cases surged.

Joseph never got to take the admissions test. She barely knows her high school teachers now that she takes all her classes online at home in Islip Terrace, N.Y. She missed out on seasons of varsity cross-country and track, and lost contact with the coach who “used to give us really good life advice.” During the five months she was furloughed from her job at Panera Bread, she spent the money she’d been saving for college. And while she’s back at work now for about 28 hours per week, often dealing with customers who refuse to wear face masks, she is worried not only about whether she will be able to afford college in the fall but also about whether it even makes sense to enroll if she’ll be sitting at home taking classes online.

“I can’t go to college with $900 in my savings account,” says Joseph, 17, a senior at Central Islip High School. “I literally just thought, What if I took a year off, maybe a year or two, and tried to wait till things were back to normal? I definitely thought, Maybe I just shouldn’t go. Maybe it’s not worth it.”

Millions of students across the country are wrestling with similar decisions. Estimates from U.S. Census Bureau surveys conducted biweekly since Aug. 19, 2020, indicate that anywhere from 7.7 million to 10 million adults canceled plans to take postsecondary classes last fall because of financial constraints related to the pandemic. The number of high school graduates who immediately went on to college in fall 2020 declined 6.8% compared with the previous year, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The drop was more stark at high-poverty high schools, where the number of graduates enrolling in college fell 11.4%, compared with a drop of 2.9% at low-poverty high schools.

It’s the latest example of how the pandemic is hindering educational opportunities for the most vulnerable students, likely limiting their career options and earning potential. And as more people lose access to higher education, the country will feel the consequences of a less educated workforce. “Our economic recovery is at stake,” says Sara Goldrick-Rab, founding director of the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The drop is being felt most by community colleges, which educate more than a third of U.S. college students and which serve as an entry point to higher education for many first-generation and low-income students. (Applications are actually at record levels at many of the country’s most selective universities this year after they suspended SAT and ACT requirements.) In the fall 2020 semester, freshman enrollment across all colleges plummeted a record 13% from a year earlier, and at community colleges, the drop was 21%, with declines concentrated among Native American, Black and Hispanic students, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

The same troubling pattern is discernible in who is now applying for college. According to data from Common App, which is used by more than 900 colleges, total applications grew this academic year, but the number of first–generation applicants dropped.

“It’s a lost senior class,” says Sara Urquidez, executive director of the Academic Success Program, which provides college counseling to 15 public and charter high schools with large low-income populations in Dallas and Houston. For the students thwarted by the pandemic, she says, “it’s a cycle of poverty that will continue for another generation, because the Class of 2021 didn’t get the same opportunity that their wealthier counterparts are going to get to be able to go to college.”

The number of students completing the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) also declined 9.1% by March 5 compared with this time last year, and fell more sharply at high schools serving large populations of low-income students and students of color, according to a tracker by the National College Attainment Network (NCAN). FAFSA completion is “the proverbial canary in the coal mine,” an indicator of whether students will enroll in college, says Kim Cook, executive director of NCAN. “We’re afraid they’re just taking themselves out of the game,” she says. “They have decided it’s just not possible.”

Across the U.S., campus tours have gone virtual. Counselors who once displayed seniors’ college acceptance letters in school hallways and who organized celebratory pep rallies have resorted to emails and slideshows to try to motivate students. Many high school seniors are isolated from friends, teachers and counselors and are taking on extra jobs or caregiving roles at home to help their families. In this lonesome environment, they’re expected to plan their post-graduation future.

At times, Joseph has felt as though she has to do everything on her own, with little help from the adults in her life. Her mother, who grew up in the Caribbean island nation of St. Lucia, didn’t attend school in the U.S. and can’t offer much guidance. It’s been tough to get one-on-one attention from school counselors who are outnumbered by hundreds of students, and she can’t stop by a teacher’s classroom to ask for a recommendation letter. “It’s like no one’s there to check in on us. We only have ourselves,” says Joseph. “And I get that older people are stressed out too, so it’s really hard to figure out what to do right now.”

For those from affluent families, the option may be a gap year to take an unpaid internship, explore a hobby or start a community-service project until things get back to normal. Outdoor-education programs like Outward Bound, which can cost thousands of dollars, saw a surge in demand over the past year.

But that’s a “romantic idea that really gets under my skin,” says Cook, who warns that low-income students who delay college might never enroll once they lose the resources they had access to in high school. “I don’t even want to call it a gap year because I don’t believe they’re coming back.” Studies show that students who delay college are less likely to earn a bachelor’s degree than students who enroll in college directly after high school.

On top of school-related challenges, many high school seniors are feeling the weight of the country’s simultaneous crises and juggling multiple roles to keep their financially strapped families afloat. In Boston, 17-year-old Kimberly Landaverde’s family has worried about making rent since her parents lost work at the beginning of the pandemic. Landaverde, a senior at Boston Latin School, is communicating with their landlord because her mother and father don’t speak English, all while attending virtual classes, staying up late to submit college applications and then poring over her parents’ tax forms to apply for financial aid.

“I go from filling out my college applications to then checking in and filling out our rental-assistance applications,” Landaverde says. She cried out of relief when she got her first college acceptances.

For much of this school year, Milan Powell looked after her little sister and her cousins’ children during the day at home in New York City, sometimes tuning in late to her own online classes because of the time spent helping the younger children. “This is probably the worst year to be a senior,” says Powell, who attends the Young Women’s Leadership School of East Harlem and who finds it difficult to focus on school when her world is in such turmoil.

“If your grades have been impacted because you’ve been panicking every day about the fact that you’re in a pandemic, and not worrying about your schoolwork, well, your scholarship opportunities are kind of down the drain,” says the 17-year-old. “For a lot of people, myself included, if they don’t get that grant or scholarship, they just can’t go.”

Countless high school seniors have lost contact with their schools or given up on college, at least for now. In Miami, Othniel Rhoden was on track to be the first in his family to attend college this fall, but the 18-year-old senior at Booker T. Washington Senior High School grew discouraged after a year of not seeing friends or being able to pursue his passions for dance and video-game design, which he’d planned to study in college. He’s decided not to apply for the fall semester after all.

“This pandemic has really killed my ambition for school and other stuff I had a passion for,” says Rhoden, a participant in First Star, a nonprofit that helps students in foster care apply to college. “It’s like a part of me is missing.”

Rhoden also feels a responsibility to help support his family. He spends weekdays tuning in to virtual classes in the same room as his six younger siblings, then works weekends as a beach attendant at a Miami Beach hotel, making $9 an hour. “It was bills on top of bills, and my mother needed help with that, so I stepped in,” he says.

His mom and his First Star counselor have been encouraging him to apply to college in the fall, and he has promised to think about it. “Maybe going to college could open another doorway for me to help my family out,” says Rhoden.

Lyndsey C. Wilson, the CEO of First Star, says there was a drop in the program’s Class of 2020 students who went on to two-year or four-year colleges and an increase in those who instead took jobs or joined the military. “It’s incredibly worrisome,” she says. “If the numbers continue to play out the way that they are, we’re going to have a lot more young people working for jobs that aren’t providing a living wage.”

Students in low-income households were much more likely to cancel plans to take college classes than those in high-income households, according to the Census Bureau surveys, which is why experts worry that the students who are forgoing college are the ones who need higher education most. A growing number of jobs now require a post-secondary degree, and nearly all jobs created during the recovery from the Great Recession went to workers with at least some college education, according to a Georgetown University report. Americans with just a high school diploma face higher rates of unemployment and earn $7,300 to $26,100 less each year than those with an associate’s or bachelor’s degree, based on median weekly earnings.

Urquidez, the college counselor in Texas, has struggled to reach students online and get them to tune in to virtual sessions on financial aid. In some cases, she doesn’t know where students are, and neither do their teachers. On average at her schools, 85% of students have applied to college so far—down from 95% to 98% in a typical year. Just over a third of seniors at one of her Dallas schools attended a recent in-person event to take yearbook photos, order their cap and gown, and discuss post-graduation plans with counselors. “Everybody’s talking about the enrollment drop for 2020,” Urquidez says. “I think that it’s going to slide further for 2021.”

Typically, during an economic downturn, college enrollment goes up as people who are unemployed return to school. Last spring, Goldrick-Rab expected community colleges wouldn’t be prepared to accommodate an influx, but it never came. That’s hurting colleges, which need students and the tuition they pay to keep classes going. Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, said colleges are facing “a crisis of almost unimaginable magnitude” because of declining revenues and the new costs of operating during a pandemic.

It falls to people like Erica Clark to try to reverse that enrollment trend. Clark, a guidance counselor at Booker T. Washington High School in Atlanta, is shepherding nearly 90 seniors through their college applications, largely at a distance, hosting virtual college visits and career talks every week, sending reminders about looming deadlines. She can’t pull students out of class or ask them to stop by her office anymore, so she tries to gauge how they’re feeling over Zoom, and she has lost countless nights of sleep worrying about them. She tracked down one student on the job at Foot Locker to get her to complete a missing form. “I know it sounds crazy,” Clark says, “but I just have to meet them where they are.”

“It becomes very overwhelming when you know that this student was destined for greatness, and now I can’t reach them,” she says. Perhaps because of the extra effort, more of Clark’s students have applied to college this year than last, but she’s now concerned about getting them to actually enroll. As graduation nears and they await scholarship decisions, more of them are having second thoughts about college and considering working full time instead or joining the military to cover tuition costs. “It’s like doors are being closed a little bit more to them,” she says. “I just don’t want them to give up the idea of going to college.”

Ellen Peyton, a college and career readiness teacher at Madison Shannon Palmer High School in Marks, Miss., shares Clark’s concerns. In October, she organized a drive-in event to help families submit applications for college financial aid. Students and their parents pulled up to a computer in the school parking lot and filled out the required forms from their cars, while counselors offered help from 6 ft. away. But by March, 34% of her students had completed the FAFSA, half as many as last year at this time, she says, and about 40% of seniors aren’t on track to graduate on time. She worries the pandemic will create a generation of students who don’t get the opportunities they deserve. “These are young adults, and they’re coming into their place in society,” Peyton says. “This is a big change in their life, and it has the ability to make or break their future.”

The State University of New York (SUNY), one of the country’s largest public higher-education systems, saw applications fall about 11% overall as of March 1 compared with last year, and even more among students of color. In response, SUNY eliminated application fees for low-income students, started offering free online job training and college prep to low-income New Yorkers, and launched an outreach program to get under-represented high school students to apply. “If you throw barriers in their way, they’re not going to come. And it’s going to hurt the university system, and it’s ultimately going to hurt society writ large. You’re just going to further the economic inequality all across the country,” says SUNY chancellor Jim Malatras. “And that’s a moral failure on our part.”

At Compton College, a community college in Compton, Calif., serving mostly Black and Latino students, enrollment fell 27.5% in fall 2020 compared with the previous year. “I expected a decline in enrollment,” says college president Keith Curry. “But I didn’t expect this.” The school is working on outreach to students who had been enrolled at Compton in spring 2020 but withdrew during the pandemic, offering them more financial aid, and improving partnerships with K-12 districts to connect with prospective students.

Congress directed nearly $40 billion to colleges and universities, which must spend half the money on emergency financial aid for students, as part of the $1.9 trillion relief package passed March 10. Higher-education advocates had asked for $97 billion, and many argue that improving college accessibility and affordability is critical if today’s high school seniors are to become the country’s future leaders. President Joe Biden has also proposed making community college tuition-free to boost college access for more students and rebuild the economy. “We’re supposed to be the future,” Rhoden says of his generation. “And I’m not sure how the future will be for us.”

These days, when she isn’t working or taking classes, Twyla Joseph is watching YouTube videos with her mother or binge-watching Criminal Minds while waiting to hear back from the colleges she applied to. She’s looking forward to the day she can once again go to concerts with friends and volunteer with the immigrant-rights group Make the Road New York.

The pandemic has forced her to rethink her plans and expectations for the future. Because she never was able to take the SAT, she applied only to schools that did not require it. She once considered applying to historically Black colleges and universities in other parts of the country, but to save money and stay closer to her family, she’s now set her sights on the City University of New York or SUNY colleges. It will depend on how much financial aid she receives. She’s also reconsidering her original career goal of becoming an occupational therapist; it would require grad school, and the additional expense and years of schooling are not something Joseph wants to commit to when the future is so uncertain. Instead, she’s planning to study social work or psychology.

One thing that hasn’t changed is her excitement about what college could bring: psychology classes, dorm life, more independence. “I actually want to go to college and learn and meet new people and have different experiences and just make memories,” Joseph says, “if I can do that in a pandemic.”

Cover: Styled by Marcus Elliott; Hair by Naeemah Lafond; Make-up by Cherry Le; Prop Styling by Jessica Oshita

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- See Photos of Devastating Palisades Fire in California

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com