There are many ways to photograph a black person, and it’s easy for things to go horribly wrong. America’s long history of racist imagery makes that quite clear. Wayne Miller, a white man, was notable for doing it right. In the mid-20th century, a time when American visual culture was suffused with photographs that reinforced demeaning notions about black people, Miller created deeply empathetic images with a understated, yet unmistakable anti-racist intent. He made his best known photographs of African Americans on Chicago’s South Side, between 1946 and 1948. But they were not his first.

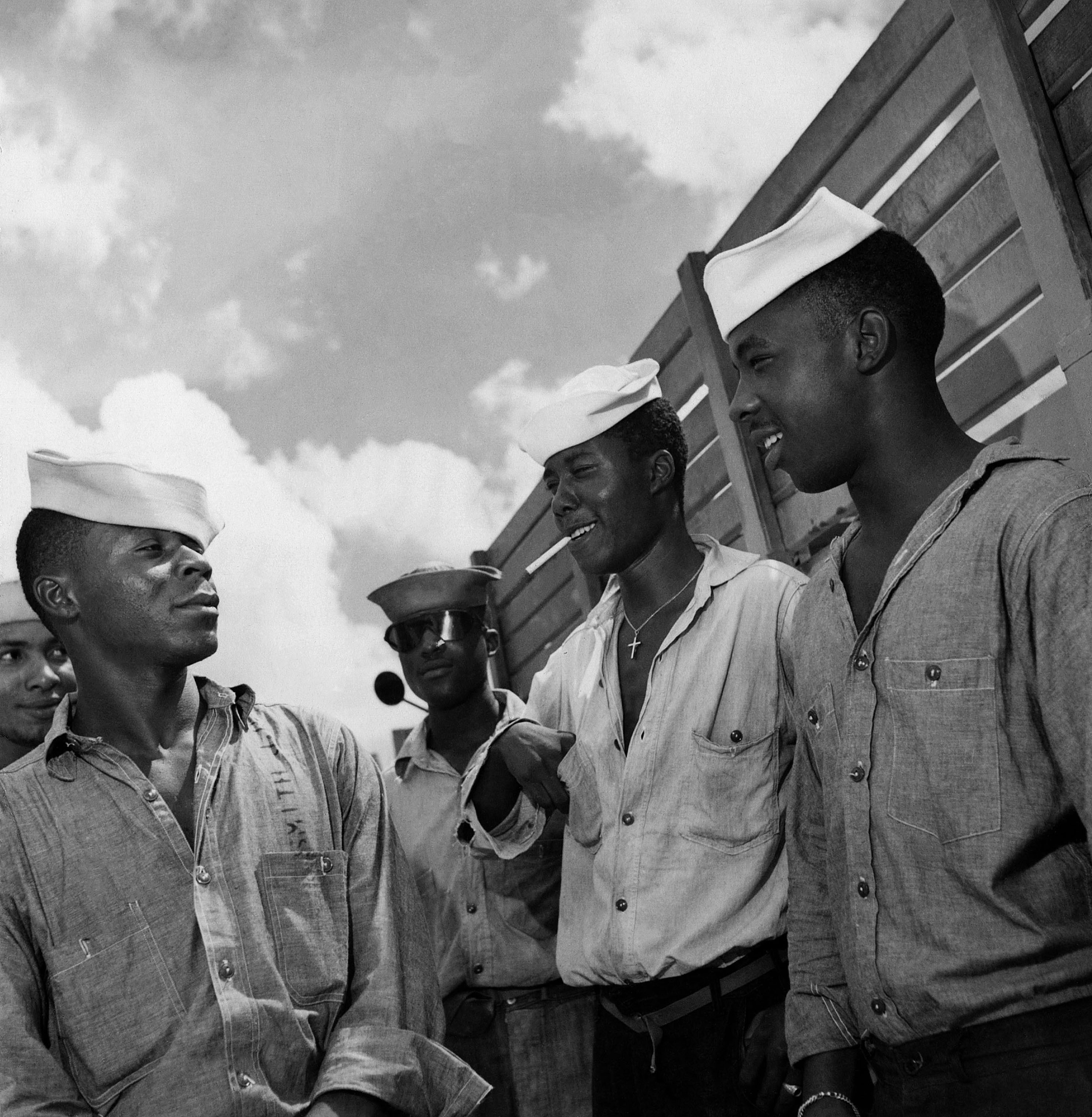

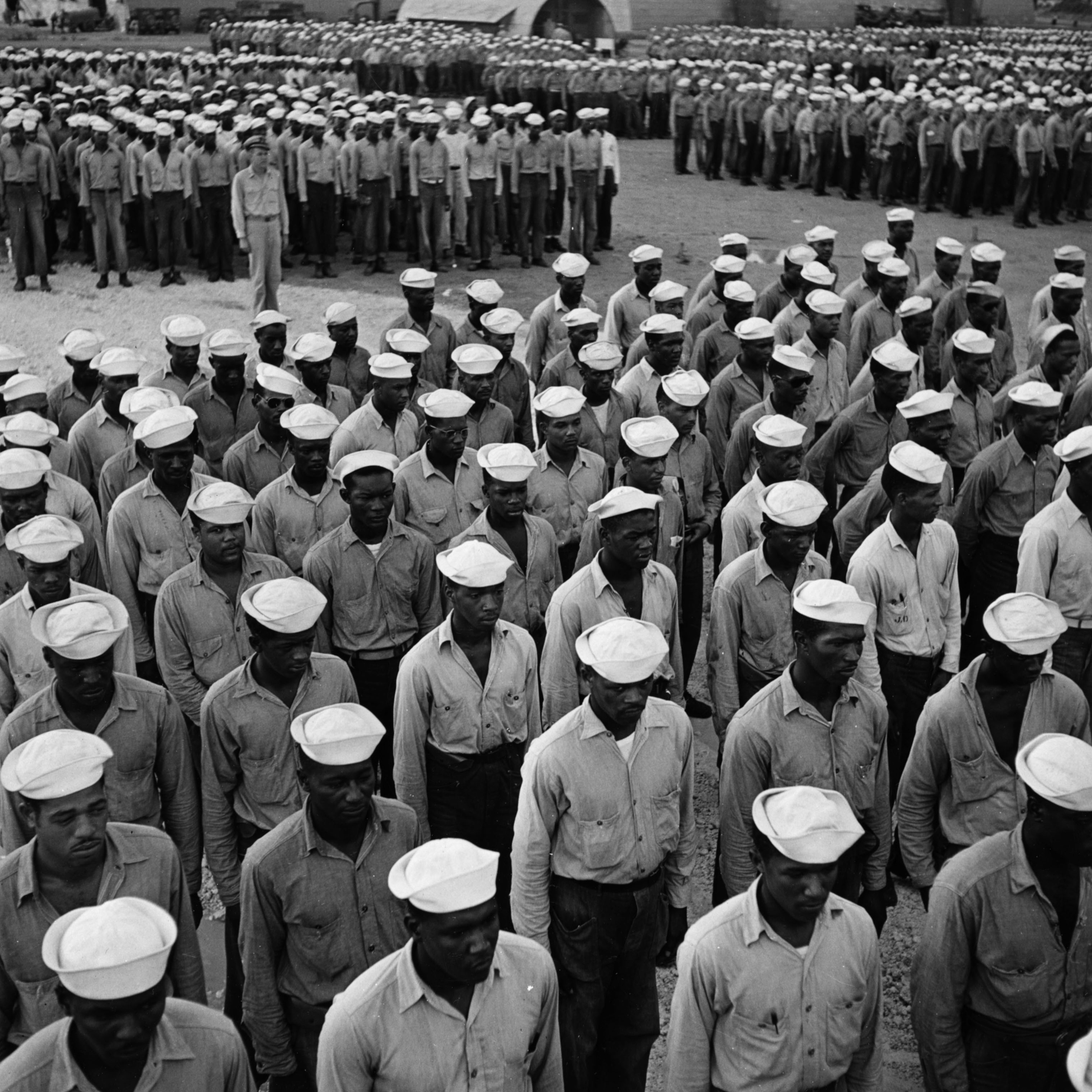

In 1944 and 1945, while serving as a U.S. Navy photographer, he created a photographic series about a segregated all-black unit that was assigned to the Naval Supply Depot on Guam. The men called their unit “Pot Luck,” and that was the name that Miller gave to the book that he planned to publish about them. The book never appeared; its maquette, or mock-up, was lost until 2018, when one of Miller’s daughters rediscovered it. And what she found, images from which are published here for the first time, reveals a gifted young photographer grappling with the complexities of race in American culture.

By 1945, when Miller made his Pot Luck photographs, which appear in the maquette alongside text that he wrote to accompany them, African Americans had long been irresistible objects of white curiosity. Racist ideologies created ways of seeing that made black life seem exotic and threatening — something to be explored and explained. Generations of white photographers had met the demand for images of black people, often by making images that reproduced ugly stereotypes of black inferiority.

Miller’s decision, in 1941, to study photography at the Art Institute of Los Angeles followed closely on the rise of social documentary photography, a movement that, among other things, rejected the old ways of seeing African Americans. Its adherents wanted to use their cameras as weapons against injustice. The plight of workers and racial minorities particularly concerned them. Social documentary photographers — such as Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Gordon Parks and Marion Post Wolcott, at the federal government’s renowned Farm Security Administration documentary unit, and Aaron Siskind, Jack Manning and Marion Palfi, members of the radical Photo League — produced images of black people that spoke with an artist’s power and a sociologist’s clarity. Their message was unambiguous: People of all races were equal and equally deserving of the rights of American citizenship.

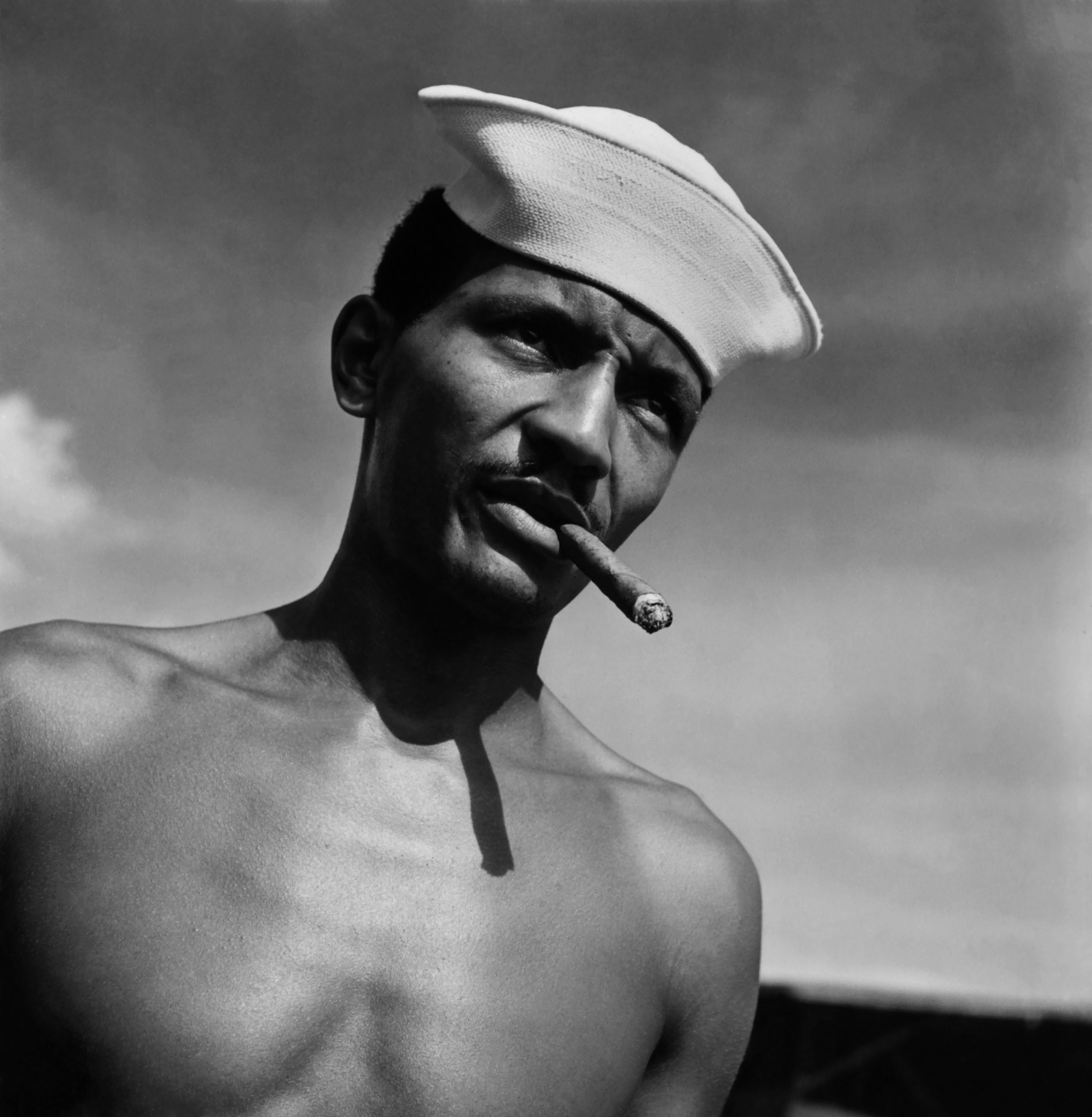

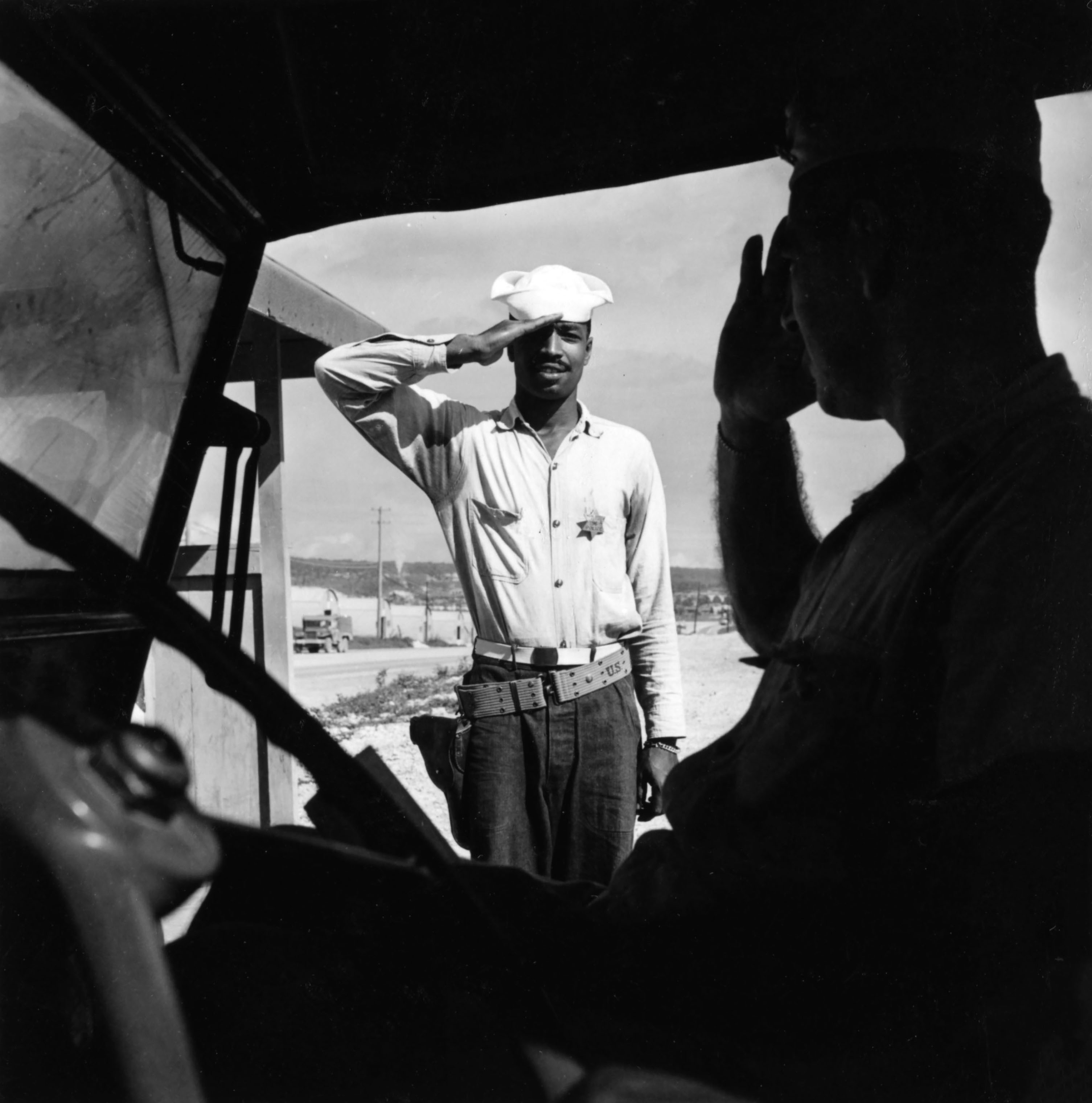

The photographs that Miller made after leaving art school to join the Navy show that he had absorbed social documentary’s modernist style. Sharp focus, uncluttered framing and crisp contrast between blacks and white make the images in the Pot Luck series, like his other work for the Navy, instantly legible. Recurring diagonal lines give the photographs energy. Miller was already a competent professional photographer, working in a by-now-conventional style.

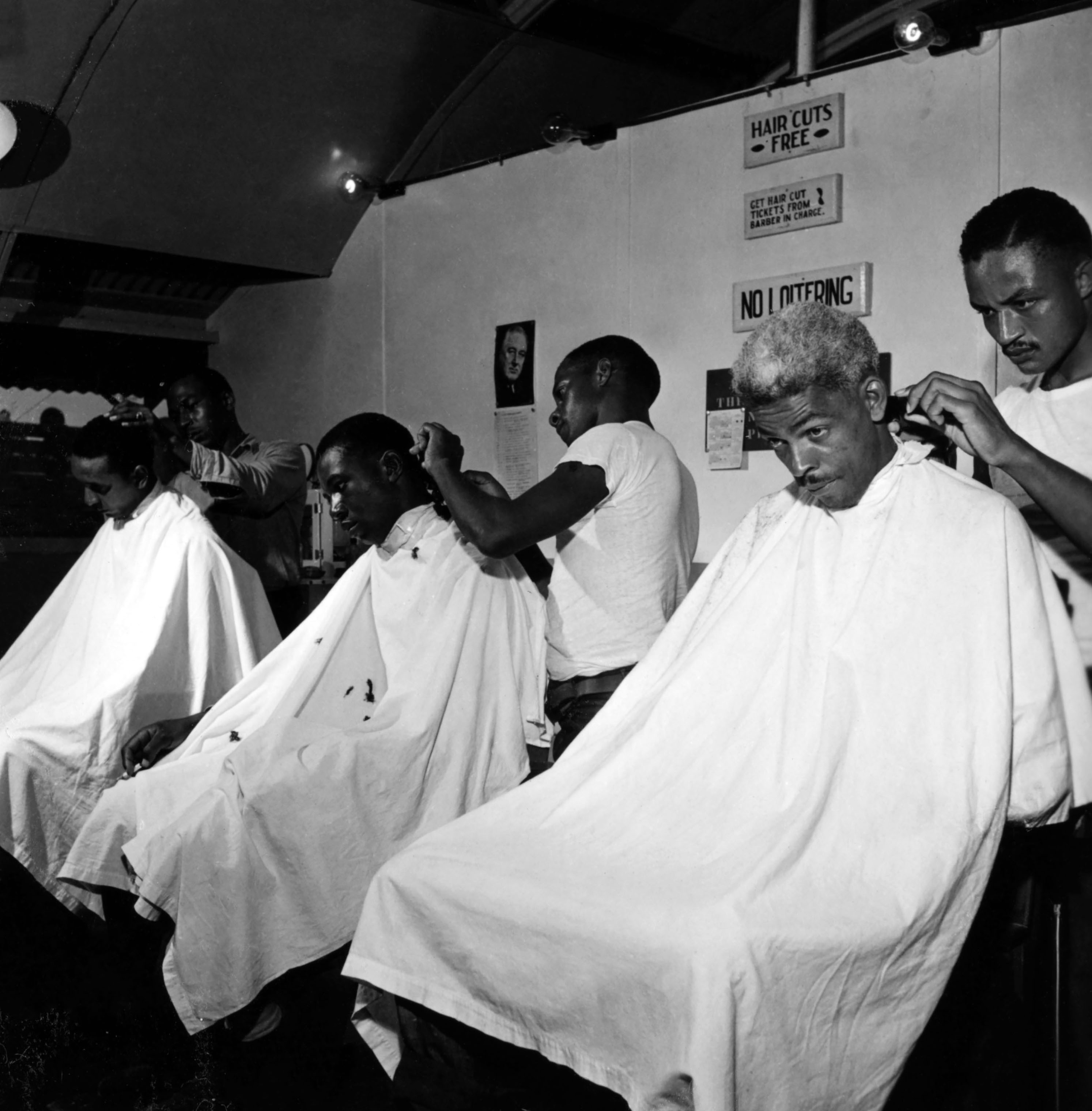

But while Miller’s style may not yet have been distinctive, his concern for black servicemen was. Throughout the war, few photographers paid much attention to African American soldiers and sailors. Gordon Parks, who was black, and Toni Frissell, who was white, are notable exceptions. All three photographers adopted similar photographic strategies while making an implicit argument for racial equality. Miller’s images, for instance, emphasize the just-like-white-people normality of the men in the Pot Luck unit. He shows them playing baseball and ping-pong; making music together; doing laundry; praying during a chapel service; and getting haircuts in the base barbershop. Overwhelmingly, however, the photographs are about the heavy labor that the men performed in order to keep the American war machine moving. These are hard-working, patriotic men who are fighting for freedom abroad and deserve to enjoy it when they return to civilian life.

Miller’s text, which is believed to have been inspired by conversations with the sailors, attempts, rather unconvincingly, to mimic the cadences of African American speech. He invents an unnamed sailor and puts words into his mouth to mirror the concerns of the photographs. “We work long hours and welcome rest. We command each other’s respect and the respect of those we meet,” the sailor says. “Why, man, we practically run the Navy and part of the Army.” Miller’s stand-in sailor also wants his presumably white audience to know that, like them, “We are average American citizens.”

Yet Pot Luck’s text also introduces an element of suppressed anger over racial discrimination, something that cannot be discerned in the photographs. In the segregated armed forces, most black servicemen and servicewomen were assigned to support roles, where they served as cooks, stewards, drivers and laborers. Although some of the Pot Luck men had been trained to perform highly skilled tasks, they remained laborers. Miller’s fictional sailor gives voice to the frustration that the men felt when he says that, “There is only one gripe I feel is justified. …We can’t advance.”

It’s probably just as well that Pot Luck never saw the light of day. The presumptuousness of creating a text that speaks in the voice of an African American sailor would almost certainly have embarrassed the more mature Miller of only a few years later. In his magnificent study of the black community on Chicago’s South Side, which he worked on between 1946 and 1948, his captions are informative and restrained, allowing the photographs to carry all the emotional punch. While the Pot Luck images themselves are strong, they lack the intimacy and insight that distinguishes Miller’s work on the South Side. Just as crucially, he had not developed a visual language that could convey the lived experience of racism.

Pot Luck is nevertheless a fascinating historical document and an important one — a crucial landmark on Miller’s path to becoming one of the most significant American photographers of the 20th century, and a singular window into what it can mean to document discrimination.

John Edwin Mason teaches African history and the history of photography at the University of Virginia.

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision