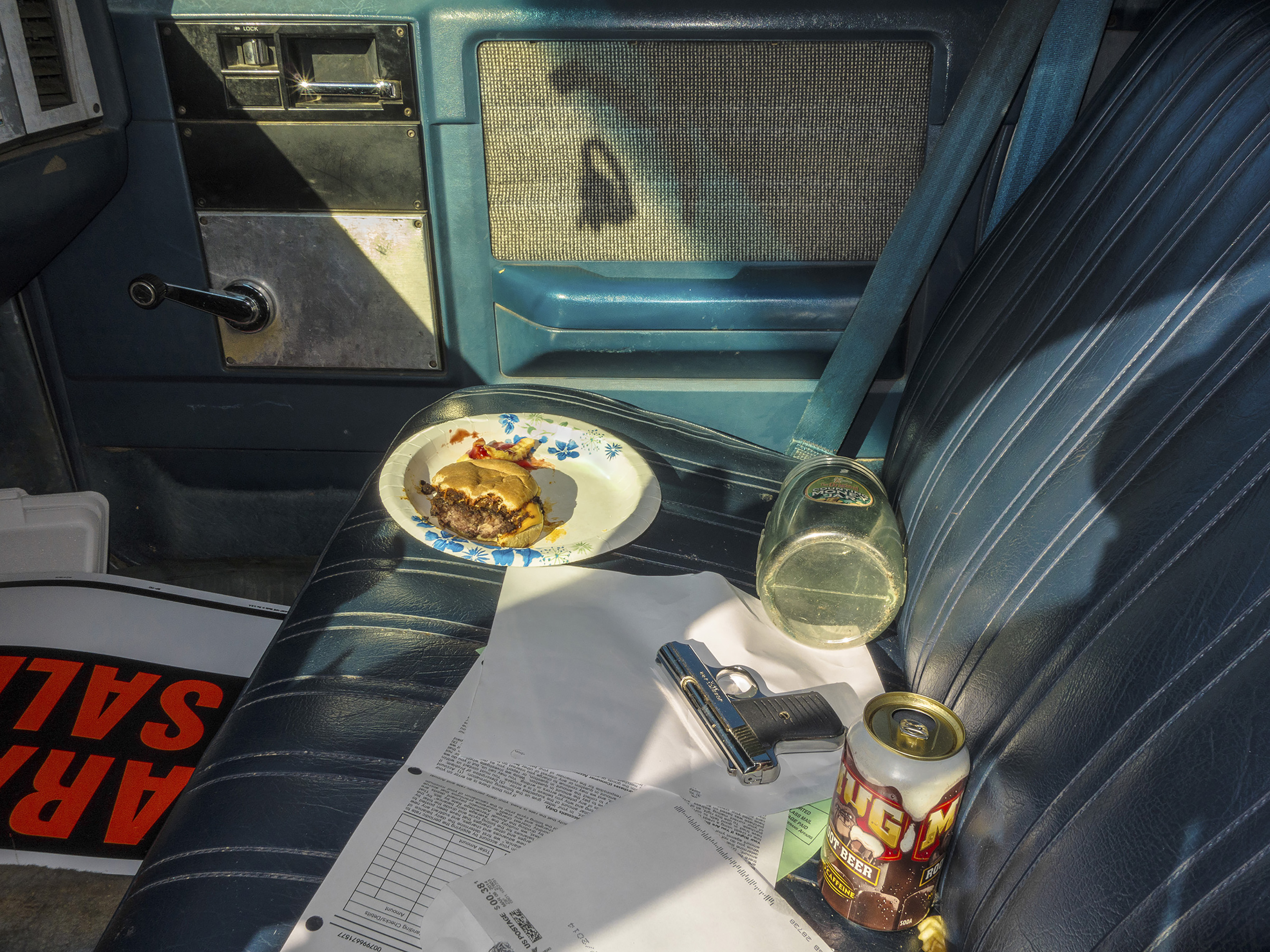

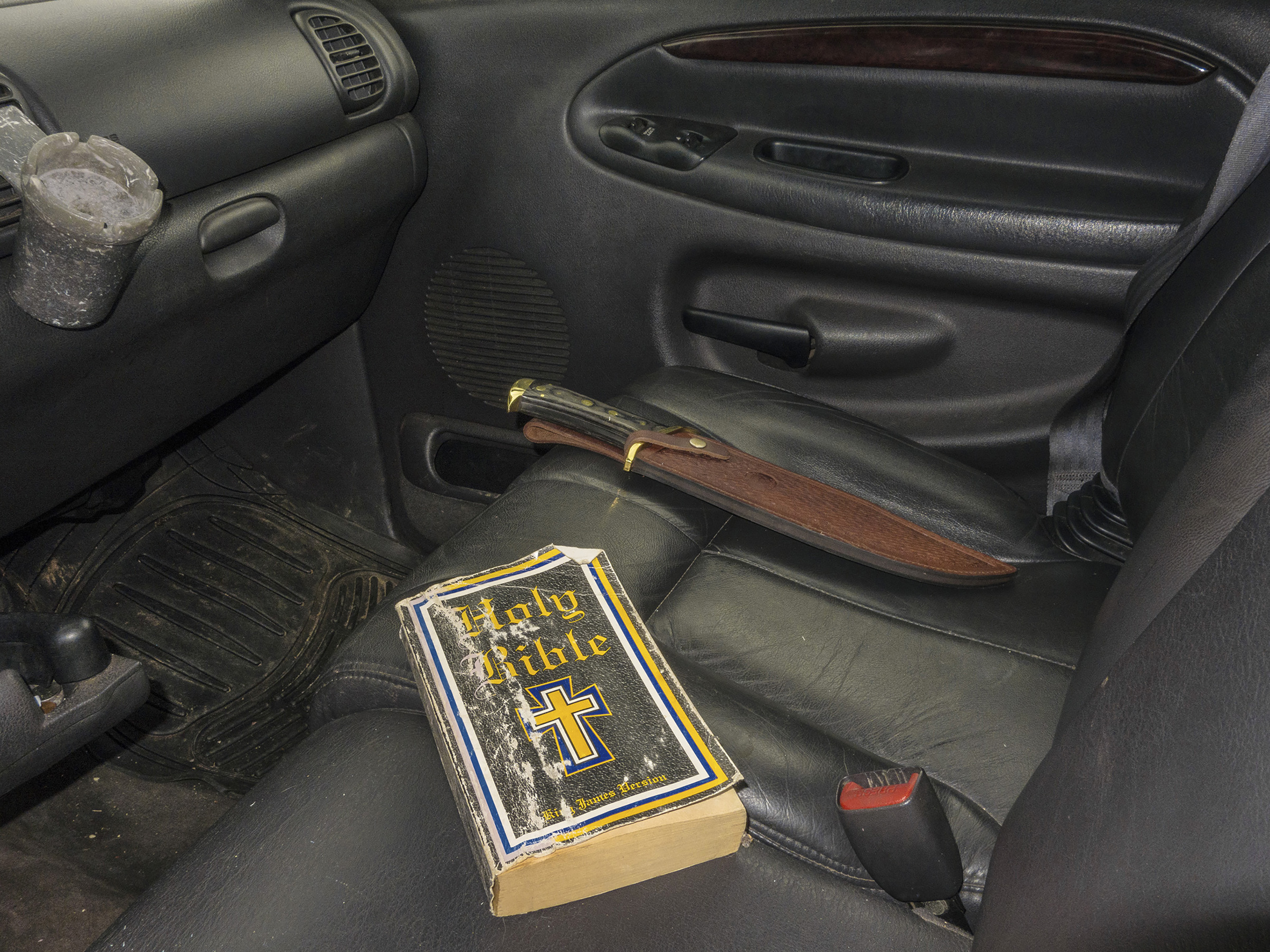

Cars are perhaps the most public of our private spaces. On the seats, in cup dispensers and on the floorboards, we store personal items, ranging from our daily necessities to miscellaneous disposable objects — or in some cases, nothing at all. But the car windows make these objects visible to passersby, granting them the ability to take a peek into who we are and enabling them to also guess about how we are.

For seven years, cars were Matthew Casteel’s way into other people’s lives. He parked them for a living, managing the Veterans Affairs hospital valet service in Asheville, North Carolina. These interactions with veterans who fought in wars ranging from World War II to Afghanistan afforded him the ability to connect with service people from various age ranges and experiences. However, the inside of their cars revealed commonalities, regardless of when they served or where they’re from: bouts with addiction, poor hygiene, or indications of their declining physical and mental health.

Casteel began taking photographs of those car interiors while at work — getting permission from those whose cars he photographed, and being careful to not capture anything that would reveal their identity. And in April, he published his most recent book, [tempo-ecommerce src=”https://www.amazon.com/American-Interiors-Jörg-M-Colberg/dp/1911306170″ title=”American Interiors” context=”body”], a collection of those photographs from between 2013 and 2015.

Hailing from a small town in Southwest Virginia, Casteel was raised in a community that preached God and country, despite the fact that his family was not particularly religious or patriotic. His grandfather and great uncles fought in World War II, but beyond that, Casteel’s interactions with service people prior to working as a valet were sparse, and his awareness of their struggles was even more limited.

As he parked their cars, though, he grew frustrated about their treatment. “The facility that I worked in is one of the best in the country,” Casteel explains. “But it’s still massively underfunded. Although the folks who work in the hospital really cared about their patients and put a lot of effort into providing care, the hospital was understaffed. I was really seeing that these veterans weren’t provided the level of support and care that they need, and certainly have earned.”

Casteel hopes that his photographs challenge the stereotype that veterans can’t take care of themselves, and that they’re all addicts. “There’s a misconception that veterans are slobs, and should be pitied or feared,” Casteel explains. But he found that it was far from that simple. From the revolvers in the passenger seat, syringes in the center console, and cans of beer in the backseat, to the meticulously clean and organized cars, he saw addiction, alcoholism, mental health issues and a general a fight for some kind of normalcy — in sum, the trauma of war. “If anything, I hope that the book is a call to action for people to demand more care and support for our veterans,” he says.

While the reality of war is something that may be hard for someone to wrap their mind around, the interior of a car is not. Casteel hopes his photographs, to a certain extent, make us feel complicit in the veterans’ struggles, because the orderliness — or lack thereof — of a car is something that we can all relate to and understand.

“What I was seeing in these cars was an illustration of the story that is difficult for many people to articulate,” Casteel says. “Nearly all of the images in the book are made from the driver’s seat because I wanted to put the viewer in the veterans’ shoes. This series attempts to give us a real, tangible sense of who a particular group of people might be, and what they’re going through.”

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders