Despite nationwide walk-outs and protests in the spring of 2018, most teachers face the same conditions — including low pay, crumbling facilities, and outdated textbooks — as they return to their classrooms this fall. But those conditions don’t only make their work difficult. TIME spoke with teachers across the country about their personal financial situations to see how wage stagnation has affected their day-to-day lives. Read their stories below.

Hope Brown, 52

U.S. history teacher at Woodford County High School in Versailles, Kentucky

The reality is that we have to spend a lot of our own money for our classroom. I spend money to buy my own copy paper. I bring food for my kids. We’re given about $50 per semester that we can spend on certain things for our classroom, but we always go above and beyond that. I usually end up spending about $400 every semester.

I’ve been teaching for 16 years, and I make about $55,000 a year. I work an extra job in guest services at Rupp Arena, sometimes multiple nights a week, making $9 an hour. My husband and I also started a business leading historical tours in the summer.

Right now, I have a broken tooth that I can’t afford to have fixed. I’ve had to take a sick day before because I didn’t have enough gas to make it to school. I donated plasma twice before my first pay day this year just for gas money. I was really embarrassed when I first had to start doing that because I think of myself as a professional. I have a master’s degree.

I wish people understood exactly what it takes to make a classroom work. Teaching is a science and it is an art, and we work really hard to be able to provide for our students. The schools in Kentucky are not failing like our governor wants people to think that they are. We do a really good job educating all kids that come before us. But we are not paid for the work that we do. I go in at 5 a.m. and I get off at 4 p.m., and usually that’s because I have to go to another job.

I love what I do. My kids are fabulous. There is not another job where you could have as many highs, as many lows, as much connection, as much challenge as there is in teaching. I can’t think of another job — maybe an ER doctor, I don’t know — where I can get the feeling that I do from teaching.

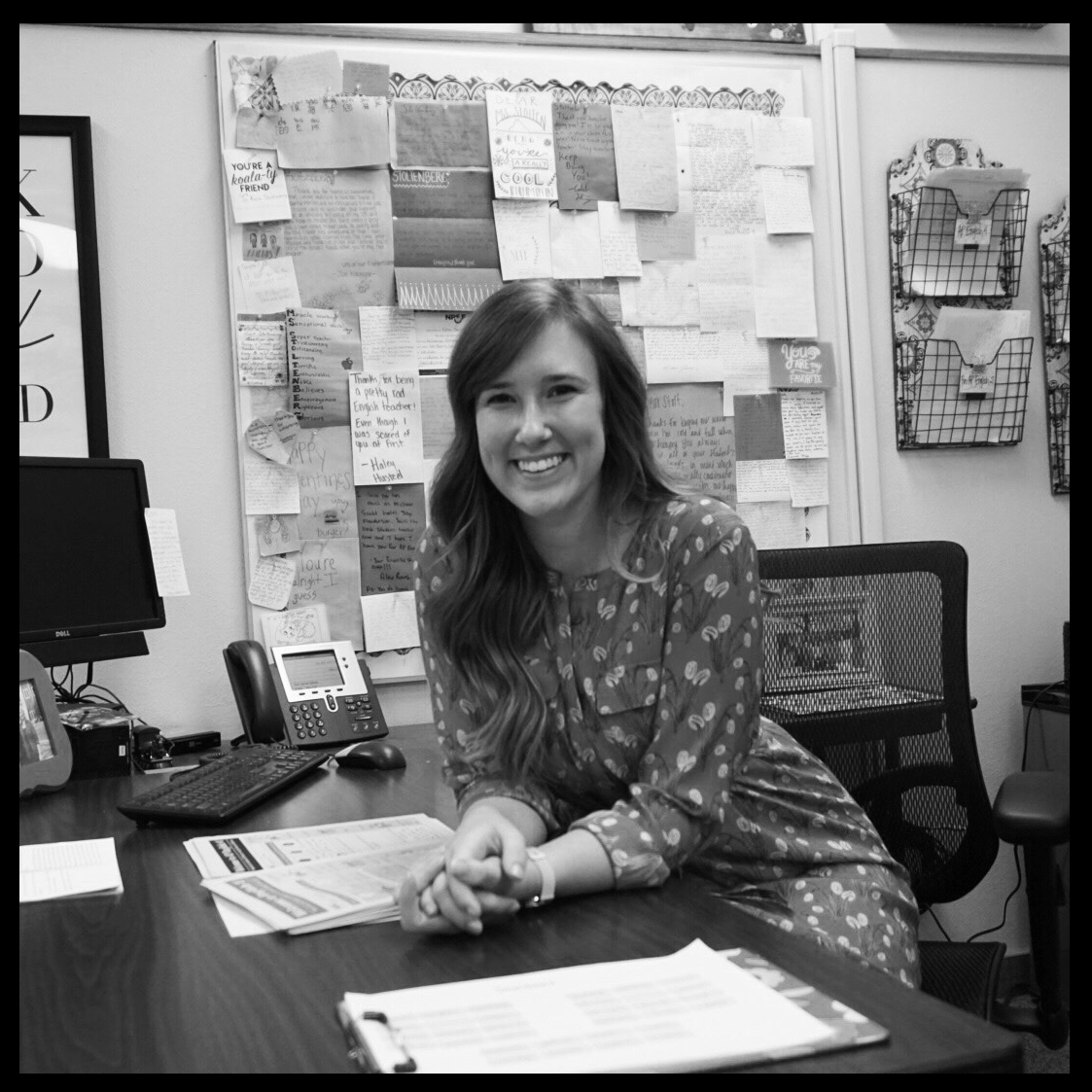

Kara Stoltenberg, 28

Language arts teacher at Norman High School in Norman, Oklahoma

I knew the pay wasn’t great, but I don’t think I truly understood in terms of expenses, in terms of just being able to get by, how close I would be cutting it. I make about $34,000 as a teacher. Right now, I can’t save, I can’t buy a car, I can’t buy a house, but I can get by. The only thing that I’m able to save is my tax return. My battery in my jeep died a few months ago, and I just kept thinking, ‘When that car dies, I’m going to have to buy another one,’ and the monthly payment — I just don’t know how I’ll do it.

My friend is getting married in Salt Lake City next month, and he messaged me a month ago and asked if I would be able to attend the wedding. I started looking up flights, looking up Airbnbs. Even with the pay raise that we’re going to get, I couldn’t swing it financially. He understands, and my friends understand, but it’s embarrassing to pretty much say, ‘I’m working 40 hours, 50 hours, 60 hours a week sometimes, and I still can’t afford to go to a friend’s wedding.’ It’s not anything ostentatious. I don’t feel like I live a life where I am spending money left and right. It’s just really humbling to have to tell one of your best friends that, literally, I just don’t have enough money and I won’t by the time the wedding arrives.

It’s also humbling when you’re in a grocery store and people who are well intentioned find out somehow that you’re a teacher and suddenly they start talking about how little you get paid. I don’t think it’s ever malicious, but it just kind of eats away at you and you start to question your worth and question whether you should stay in education when you do make so little. I think they bring it up to show their support, but ultimately, it comes across as, ‘I can’t believe you’re still a teacher.’

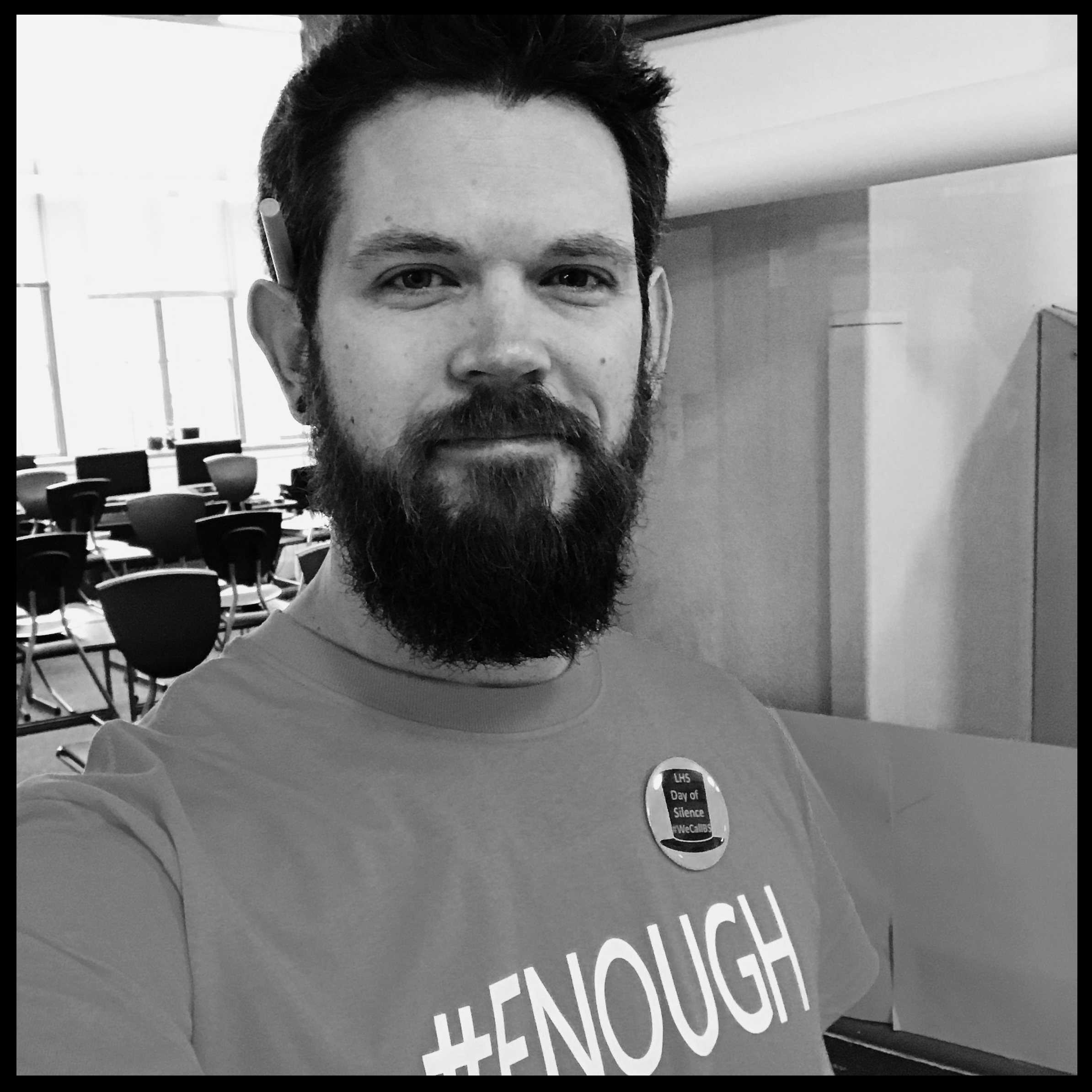

Grant Ruby, 40

Math teacher at Lincoln High School in Tacoma, Washington

I’m set to make about $63,000 this coming school year, my fifth year in the classroom. Last year I had almost $500 in student loans, all of my utilities, credit card payments, a $180 car payment. When all is said and done, I had a little more than $100 per month, and that’s not a real big entertainment budget or savings budget. In reality, it affects every part of my life. I have to decide, is that worth having to eat a cheaper meal or wondering if I’m going to have enough gas to get through the week? Do I get to go out to dinner with my girlfriend tonight, and how is that going to impact whether I can pay rent next week?

Those decisions create a lot of stress in a person’s life. I also am someone who deals with depression, and I’m dealing with all this additional stress that could be pretty easily solved by making $10,000 to $15,000 more a year — which teachers in neighboring districts are making. What we’re hoping for is competitive salaries. If Tacoma wants to continue being a world-class public school system, we need to be able to attract new teachers and keep experienced teachers. Quite frankly, if I can drive an extra 10 minutes to make $10,000, that’s an easy decision for me to make.

Read the TIME Magazine cover story about the teacher pay crisis

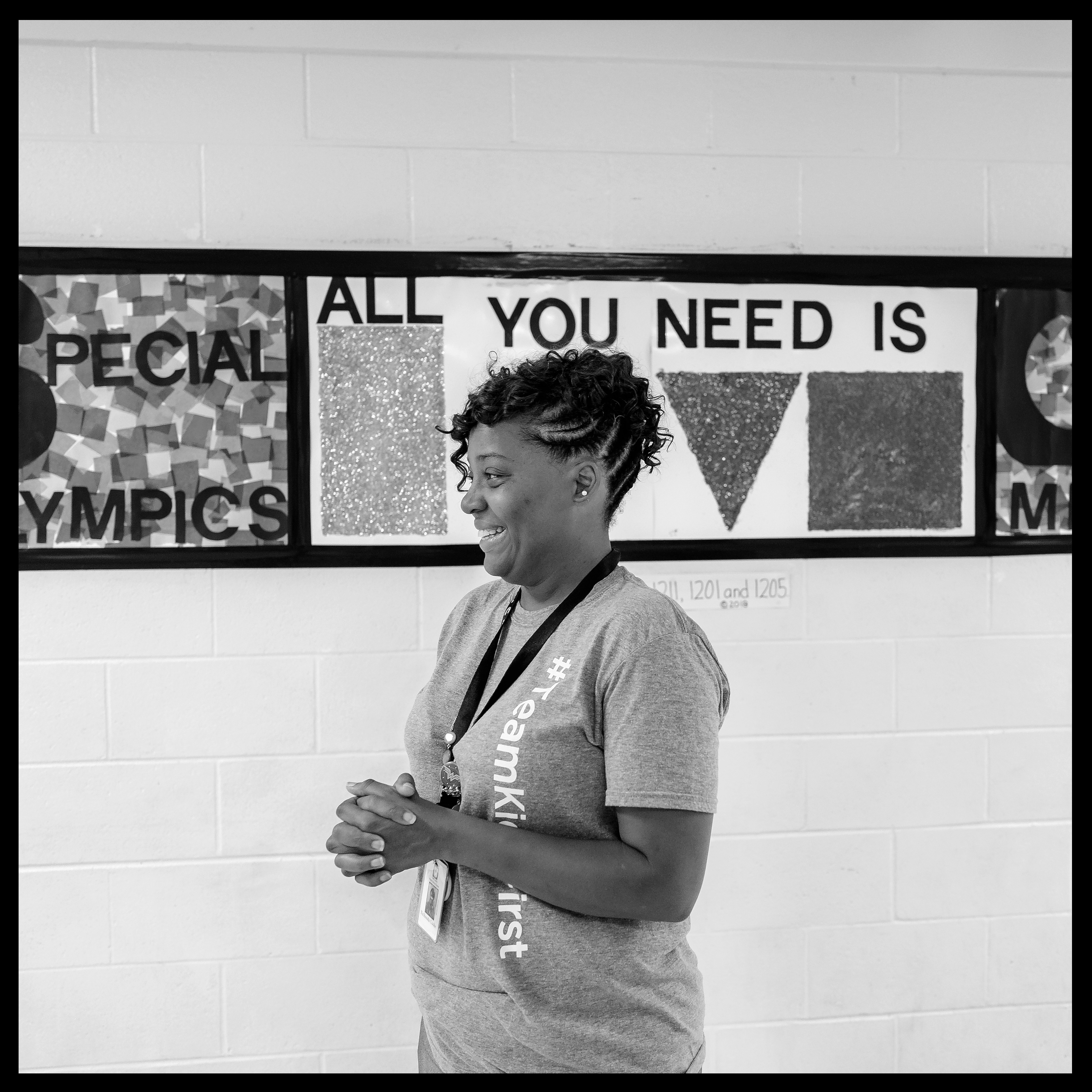

NaShonda Cooke, 43

Special education teacher at Carroll Leadership in Technology Magnet Middle School in Raleigh, North Carolina

I have been teaching for almost 20 years. I’m a single mom, I make about $69,000 a year, and I still depend on my mom sometimes. It’s not about wanting a pay raise or extra income, it’s about wanting a livable wage. We just want the appropriate amount that helps us take care of our own bills, and be able to go to the doctor whenever we need to or take care of car maintenance. I’ve been running around with a crack in my windshield for three months because I can’t afford the more than $200 deductible on my car insurance. When I pay all my bills, there’s nothing left to put in savings. I’m terrified that I won’t have anything to put toward my eldest daughter’s college education.

My youngest daughter has high-functioning autism, and for three years in a row, she went to a special day camp during the summer. But she didn’t go this summer. I can’t ask people every summer for money, for help, because even though they understand, as a mom, I feel defeated having to do that over and over again. My oldest daughter was a part of Girl Scouts, but we had to cut that. We do things closer to home. I make sure my daughters go to their doctors and dentist appointments, but myself, if I can put it off, I put it off.

If you become the teacher you’re meant to be, there are rewards other than the financial. However, utility companies do not care that you had a great day with one of your students, that you had a light bulb moment. They don’t care that you’re coaching the soccer team or anything like that. They want you to pay for the services that they provide you. I can’t tell you how many letters I got this summer that said, ‘final notice,’ or ‘disconnection as of this date.’

Nathan Bowling, 38

Lincoln High School in Tacoma, Washington

As somebody who has gone out on the speaking circuit and who has lectured at Harvard, I get job offers on a pretty regular basis, so I know what my market value is, and I know what I get paid for teaching. Basically, every year that I stay in the classroom, I’m taking somewhere between $20,000 and $60,000 a year and setting it on fire in my front yard. But that’s the bargain that I make because I want to make a difference.

I make $76,530, but the cost of living in the Tacoma area is much higher than most. I also have a sponsored podcast and I get speaking fees. I’m not in the poor house like some of my colleagues are. I’m not experiencing a ton of hardship. My wife and I make choices. We live in a house in the neighborhood where my students are. We drive 10-year-old Kias. It’s not ‘poor me.’ But I don’t want for young 20-somethings who want to be change agents to look at teaching as something they can’t do.

There’s an element of sexism in the way we talk about teachers. People talk about teachers in a way they don’t talk about firefighters and police officers, and they’re all public servants. There’s an animosity with respect to teachers that’s a function of sexism that, as I watch it happen more and more, bothers me to my core.

Keri Treadway, 37

Kindergarten teacher at William Fox Elementary School in Richmond, Virginia

I’m married and I have one 7-year-old son. My husband ended up having some medical issues and surgeries, so we had some medical debt and we rented out our house and moved in with my parents. There was a time when my husband wasn’t able to work, so it was just my salary. And it really hit home, just really looking down at my paycheck, it made me wonder, God forbid if something were to happen to my husband, I wouldn’t be able to raise my own child with what I’m making. I wouldn’t be able to pay the rent and the bills with the cost of living with the $51,000 I’m making as a teacher.

Read the TIME Magazine cover story about the teacher pay crisis

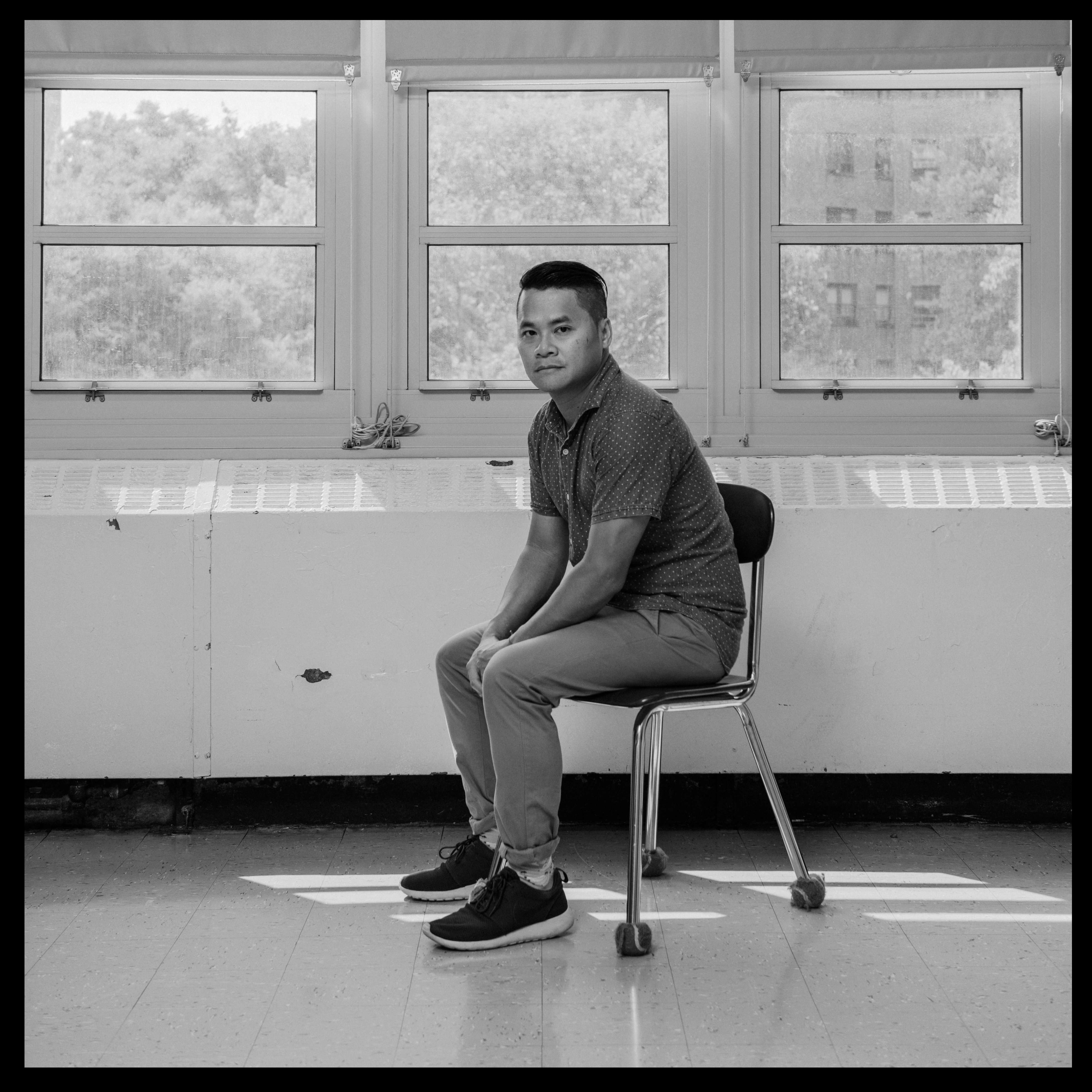

Binh Thai, 41

Humanities teacher at University Neighborhood Middle School in New York City

In New York, the unions are strong and a lot of the protections that I get here are more protective than what I’m seeing in places like West Virginia, Arizona and Oklahoma. I just started making $114,500 because I took on an additional position, and that has mitigated some of my financial struggles. I’ve been teaching for 17 years, and I’ve been working two or three jobs since 2003 just to be able to afford to live in New York City. It’s a really expensive place to live. Almost every person I know who teaches has either a second or a third job. I’m 41 and I have always had to live with roommates to split the rent.

I’m the son of an immigrant. Sending money home and making sure I can support my mom as well as support our family back in Vietnam — that’s a bit of a challenge. Sometimes, I’m sending a couple of hundred dollars per month, sometimes it’s $1,000 or more.

I can tell you that my first two years of teaching were very conflict-laden. My mom did not immigrate to the U.S. for me to become a teacher. And I think that sort of goes to where we, as a society, hold teachers. My mom really wanted me to either be a doctor or a lawyer. I can understand her motivation, having come from a third-world country and having a family that’s still struggling.

I have, in the past, applied for other positions. I have two master’s degrees. With my education and my background, I can certainly make more than I’m making as a teacher. But just the draw of teaching and the energy that it brings ultimately made me stay.

Shontèe Branton, 34

Kindergarten teacher at Joseph J. Rhoads Learning Center in Dallas, Texas

I decided during the Oklahoma walkouts that if what we were asking for didn’t pass, I would leave. It didn’t quite go the way we wanted it to go, so I decided to move to Texas. It was a really hard choice. I was teaching in the community that I grew up in, so leaving that was hard. I left everyone. I don’t have family or friends or anything down here.

In Oklahoma, my salary was between $36,000 and $38,000 after nine years of teaching and multiple degrees. I worked at Macy’s and I taught summer school and I tutored four days a week, and with that and teaching, I still didn’t make over $50,000. Then I was offered about $55,000 for just one job, teaching in Texas.

I have a family member who’s a financial planner. She sat down and helped me budget everything, and in the course of her budgeting, she said to me, ‘I don’t know how you even survive off of this.’ There are a lot of things I can’t do. I started thrift store shopping and shopping at stores like ALDI to survive. My family went on a family vacation to Mexico this year, but I just couldn’t afford to do it, which is kind of disheartening because we all have the same education — the same amount of degrees — but they chose a different career path, so they’re able to do certain things that I’m not able to do.

I spend at least $100 a month out of pocket on supplies, buying pencils, snacks, books, reading chairs and classroom decorations. It took a whole U-Haul to get it to Texas. I have more teacher stuff than I had clothes. I’m 34 and I have enough education to do something else, but I love going into the classroom. That’s my favorite thing to do.

Misty McNelley, 31

English teacher at Copan High School in Copan, Oklahoma

I work three jobs. My main full-time job is teaching. I work part-time as a veterinary technician. It’s a job I’ve had since I was in high school. Our school is on a four-day week, so on Fridays and every Saturday, I work at the vet clinic. I worked there full-time over the summer. I also own a photography business on the side.

In 2016, my son was born. And I won’t say that we were financially fit when he was born, but we were comfortable. Now, it seems like I’m having to do a lot more budgeting than I ever had to. My husband and I really want to have a second child, but we are terrified that we won’t be able to provide for another one with the way things are now. I make about $28,000, and I am the main provider of income in my household. No matter what job I have, that is always going to be the case because I have a college degree and my husband doesn’t. No matter what I do, I have to be the one to bring home the majority of the money, and I can’t do that if I’m just teaching.

Rosa Jimenez, 36

Social studies teacher at UCLA Community School in Los Angeles

I just started my twelfth year of teaching, and I’ve never been a teacher while schools were fully funded. I was laid off three times because of budget cuts, and then rehired every time. I’m a single mother, making about $73,400 a year. My 10-year-old and I live in a one-bedroom apartment that costs $1,100 a month. We still share a bed. That’s what we do in order to make it work. But now that my daughter’s in fifth grade, people start talking about college and saving for that, and I have no idea how we’re going to do that. I don’t have $300 at the end of the month to put in a savings account. That’s just not happening. The cost of living is really high in Los Angeles, and we’re just getting by.

I got an email just before the start of the school year that I’m going to share my classroom because we don’t have rooms for the classes that we have. We don’t have enough paper. We don’t have enough ink for the copiers. We’re constantly told we’re out of markers, we’re out of crayons. Some of this is basic, but more and more as teachers, we’re asked to do this amazing curriculum and incorporate technology and do all of these things. But we’re not provided with the resources to do that. I usually end up spending up to $1000 every year on supplies for my classroom. And I have my own child who needs school supplies. I mean, honestly, I try to think ahead and save some money for this occasion, but I went shopping the other day and I was like, Well, I don’t have the cash to do this. So guess what? I have to put it on a credit card, which is something that we don’t want to do. It’s hard. I have family help, I have brothers and parents who chip in, but it’s not an easy task.

I love teaching, and I love the students and I love the community, and I love doing the work that I do in community organizing. I think that is what moves me to think about this fight. It’s me and my child, but it’s larger than me. We’re not just asking for things that are going to make our lives better as individual teachers, but there need to be changes beyond the schools if people and students want to learn and live in this city in the next five years.

Read the TIME Magazine cover story about the teacher pay crisis

Jessyca Mathews, 41

English teacher at Carman-Ainsworth High School in Flint, Michigan

I constantly think that I’d love to go back to school and get my PhD in African American studies. I went into the classroom because there weren’t enough teachers of color, but lately I’ve been thinking there aren’t too many professors of color either. I’d love to teach other teachers and inspire them. But I have this innate fear that I can’t. The student loans crush you, and you can’t afford to do that again. I make $78,000 a year, but saving is just so difficult right now.

I spend a good $600 to $800 on my kids every year, buying mechanical pencils, candy for birthdays, hand sanitizer, backpacks, tickets to homecoming or prom. I had a kid who literally ran out of gas driving to school to my class one time. The next day, I gave him a gas card. I said, ‘I appreciate you still found a way to get here the first hour.’

I live in the city of Flint. I go through some of the same struggles with the water crisis as my kids. I spend $15 every couple of weeks on water bottles. If I have time to go to a water giveaway on weekends, I’ll go do it, but I know there are people who need it more than I do. If you’re doing $30 a month, and you’re doing this month after month and it’s been over two years, that’s a lot of money for a human right. It’s another thing where you fall behind — paying $200 every month on a water bill. And in the wintertime, you can’t keep up because heating bills can reach $500 in Michigan. When it comes to the financial issues of our jobs, we’re running in circles. We are not progressively building up. We’re always looking up and we’re right back at the starting line.

Jacob Fertig, 31

Art teacher at Riverside High School in Belle, West Virginia

I’m the only income in my house. I’m going into my sixth year of teaching, and this past year as a professional teacher, I pulled in $36,500. I have a wife with medical issues. I have two young children, and my daughter has medical issues. I take home about $2,000 a month, and medical costs are a significant part of that already, so I just don’t go to the doctor. We had an incident this last year where a teacher across the hall and our school nurse were going to call an ambulance for me at the school because my blood pressure was too high — like stroke high. I refused to go because there’s no way I could afford that. That would’ve ruined me.

Groceries are things that I try not to skimp on because my kids have to eat and I want them to eat healthy and well. But there have been days in the past two years where I’ve missed work because I haven’t had gas in my car to drive to school and back. I owe about $10,000 more on my student loans now than I did when I graduated college. I can’t even just afford interest payments.There have been times when I’ve had to stretch $20 in my bank account for almost two weeks.

I still spend about $1,000 to $2,000 on food and other necessities for my students. I’ve borrowed money from my parents to give stuff to these kids when they need it. I keep a stock of food in my room. In my cabinet, I keep snacks, canned food, and I keep empty backpacks, so if the kids want to take food home, the other kids don’t have to see them doing it. They can just put it in a backpack and take it. I also keep things like toiletries, tampons, all that kind of stuff.

It pisses me off that I’m having to fight for pay and I’ve got politicians whenever we’re on strike that are saying, ‘Well, it shows that these teachers don’t care about kids,’ when we have teachers before we went on strike, packing hundreds of bags of food to send home with kids. It’s like a smack in the face. That’s what gets people to leave. It’s not just the pay. It’s not just the benefits. It’s a total lack of respect.

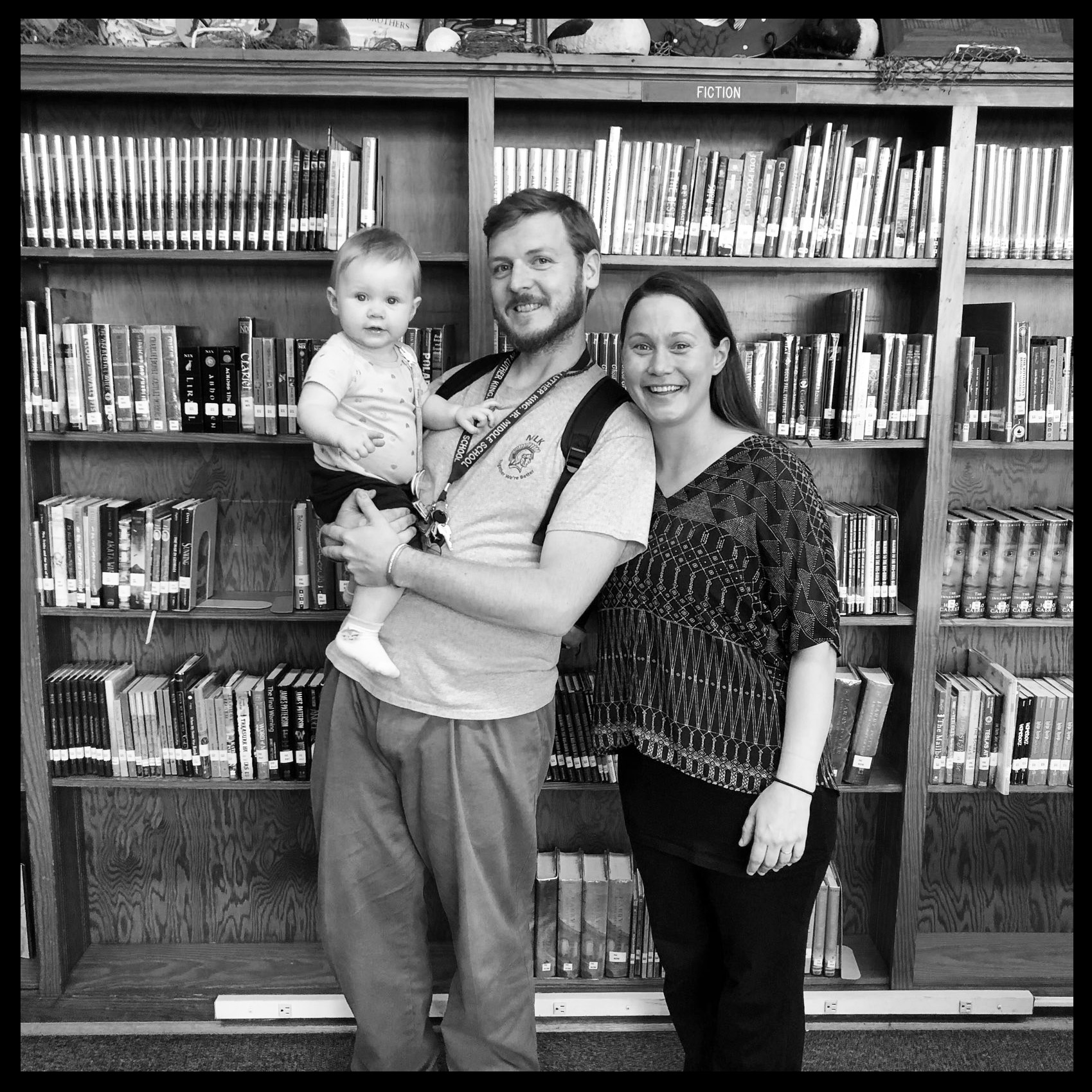

Sarah Pedersen, 32

History teacher at Binford Middle School in Richmond, Virginia

My husband and I both teach, making about $49,000 each. You would think that two teachers’ salaries would put you in the middle of the middle class. You would feel like two master’s degrees, full certification and full-time jobs, you would think we’d be sitting really comfortably. But our student loan debt is sizable. We pay about $600 a month, and we didn’t go to fancy schools.

We had a daughter a year ago. We had just expected that we would be able to have a big family, and right now, I’m not really sure we can have more than one kid. It’s so crazy to us that we might be raising an only child. We’re helping to raise other people’s kids and yet not able to afford more of our own. It’s just not what we expected.

We take these burdens on and sometimes kind of feel like Atlas — this huge weight on our shoulders. But it’s not our students’ fault, and we’re there because I love them.

Read the TIME Magazine cover story about the teacher pay crisis

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024