Perhaps no geographic location in North America is more laden with drama than the border between the United States and Mexico. Spanning approximately 1,900 miles, it follows the Rio Grande from the Gulf of Mexico to El Paso, then cuts across the desert before ending near San Diego. It’s also the busiest border in the world, with about 350 million legal crossings every year.

But it’s the illegal crossings that have made the border a daily talking point on cable news and at dinner tables on both sides. The U.S. Border Patrol stopped 303,916 people attempting to cross the border illegally in the fiscal year 2017, the agency says. While that number was a historic low, illegal immigration has remained top of mind, due largely to President Donald Trump, who campaigned on a promise to build a “wall” between the U.S. and Mexico, and to make Mexico pay for it.

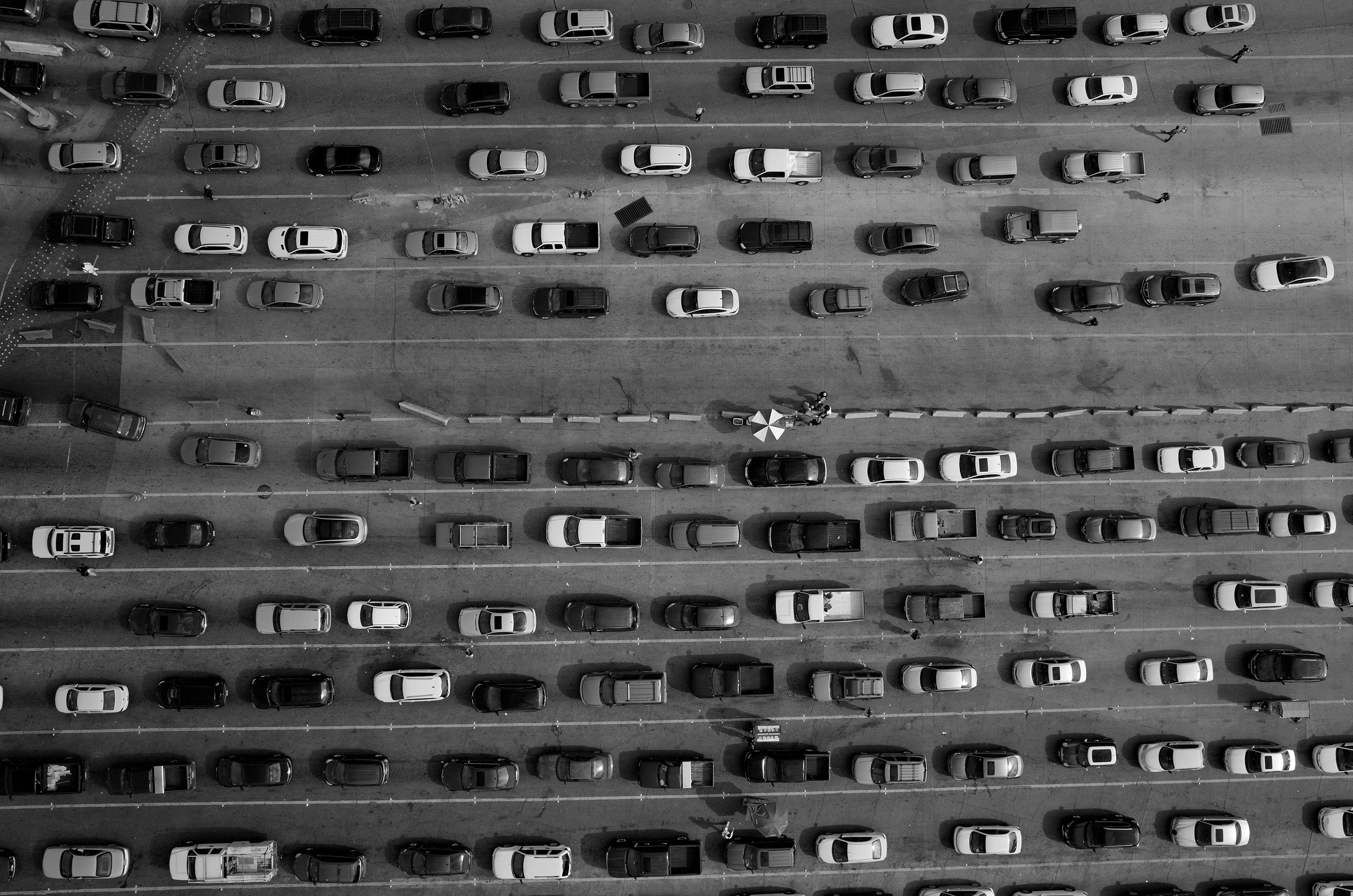

The President’s wall has yet to become reality. Still, a handful of companies are working on prototype designs, despite worries that a physical wall would be too costly, cause environmental problems, and fail to address smuggling. Others have suggested the idea of a “virtual wall,” using cameras, drones, motion sensors and other high-tech measures to spot those making the perilous crossing. Today’s border is increasingly technological, a mixture of walls, fences and devices both seen and unseen to dissuade would-be crossers. Cameras, both on the ground and in the sky on drones, are at the heart of it all. That’s what caught the attention of Belgian photojournalist Tomas van Houtryve, who has been photographing the border from above with a drone of his own.

TIME Special Report: The Drone Era

Van Houtryve often photographs from directly above a scene while the sun is low in the sky, using long shadows to give walls, fences and people depth that they would otherwise lack from such an angle. Particularly striking are the moments of humanity that he captures. Whereas the world’s other famous borders, like that between North and South Korea, are largely devoid of life, Van Houtryve captures people commuting, doing chores, and even swimming right along the border. (Water is a common theme in Van Houtryve’s work, used to show that the natural world cares not about human-drawn divisions.) But he does not turn a blind eye to the controversy surrounding the border — one image appears to show a person jumping a border fence, and we see both the subject and his or her shadow in the middle of making the harrowing leap.

For Van Houtryve, the work is also a chance to address what he views as a perversion of his preferred medium. “Historically, photography was about portraiture, fine art, journalism or just recording memories of family and friends,” says van Houtryve. “On the border, however, cameras are used for targeting and apprehension. The photographic medium has been weaponized. When I think about the vast network of lens-based technology deployed along the border, I consider it as what is probably the U.S. government’s largest and most expensive photo project in its history.”

This project was supported by a CatchLight Fellowship in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

Tomas van Houtryve is a conceptual artist, photographer and author. Follow him on Instagram.

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox