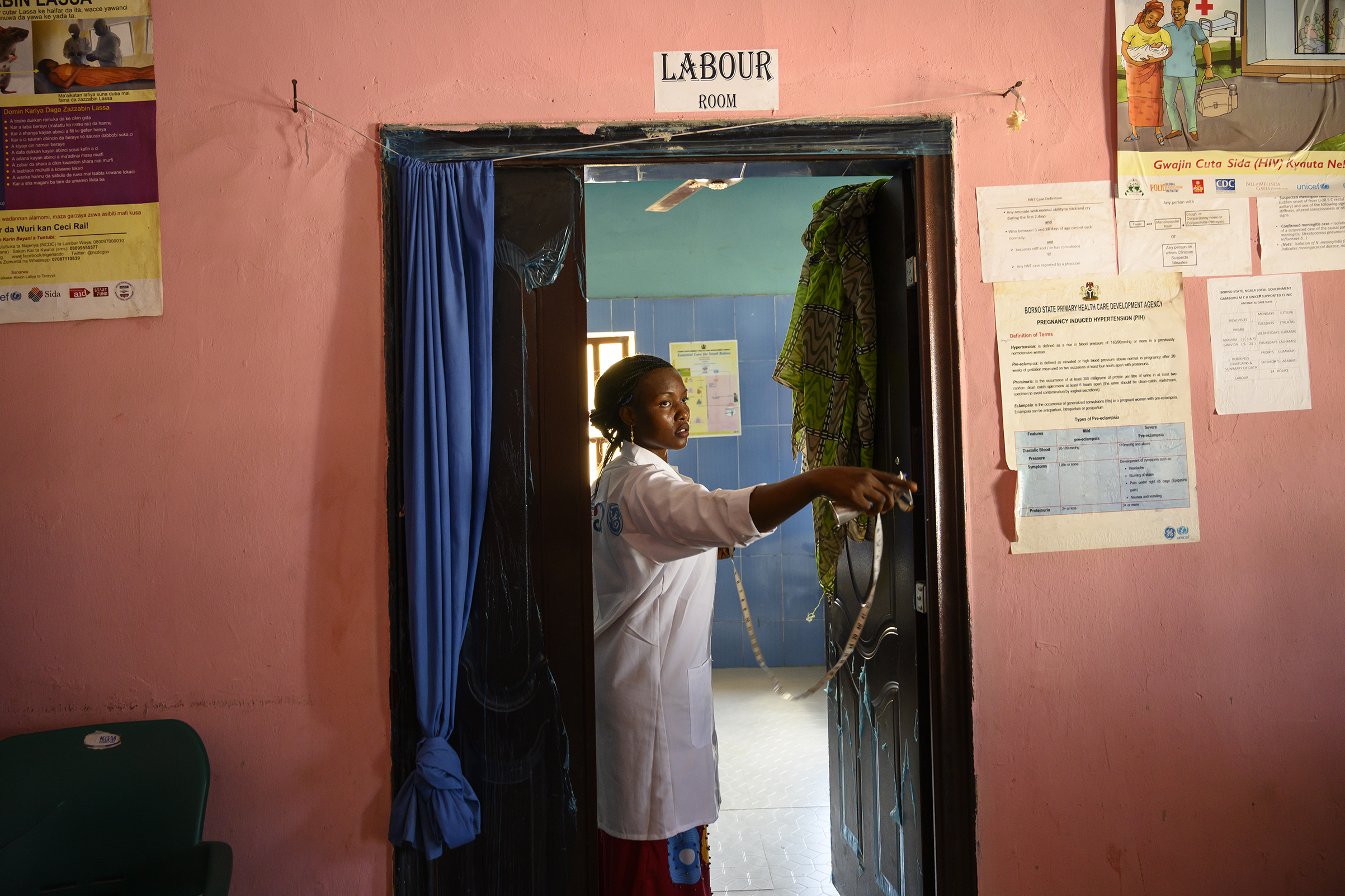

In the small, whitewashed medical clinic of Banki, one of northeastern Nigeria’s largest camps for internally displaced people (IDP), midwife Stella Aneto takes a rare pause between deliveries to catch her breath. Before wiping down the clinic’s sole delivery bed with disinfectant, Aneto glances at the clinic logbook. Two women have already given birth, and at least three others are in the early stages of labor. She instructs an assistant to prepare extra emergency supplies. Anything can go wrong when it comes to labor and delivery, but especially in a region with high rates of child marriage, malnutrition and malaria, where it’s not uncommon for midwives to tend to 18-year-olds giving birth to their fourth child.

In a bare-bones clinic that has no electricity or running water, and where the nearest hospital is 80 miles away, the chances of death in childbirth are extremely high. Yet Aneto hasn’t lost a single patient since she started working at the clinic 12 months ago. “I am always afraid of complications,” she says. “If something goes wrong, we don’t have what we need to help.” So Aneto’s goal is to make sure things don’t go wrong. And the only way to do that, she says, is to prepare. “Out here, preparing is our prevention.”

Nigeria is a risky place to give birth. Around 58,000 mothers die in childbirth in Nigeria every year, and 240,000 newborns within 28 days of birth. Despite being the wealthiest country in Africa by GDP, it ranks fourth in maternal mortality globally. But the situation is especially bad in the northeast of the country. Here in Borno state, which is at the epicenter of a decade–long Islamist insurgency led by Boko Haram, more than 6,500 newborns die every year of preventable causes—twice the rate of the rest of the country, according to the Nigerian government. And approximately 3,500 to 4,500 women die yearly because of causes related to childbirth.

Even before the conflict started, the chronically underdeveloped region suffered a significantly higher maternal and infant death toll than the country as a whole, largely because of traditional practices and a history of political neglect. When the Boko Haram insurgency started gaining ground in 2012, half of the region’s 200 doctors fled. Health facilities were looted and destroyed, leaving pregnant adolescent girls and women particularly vulnerable. At 1,549 deaths per 100,000 live births, the northeast’s maternal mortality toll was nearly double the national average of 814, according to a 2015 survey by the World Health Organization. In Finland, the average is three.

Today, UNICEF estimates that only a handful of obstetrician-gynecologists remain in the region, centered in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state and the biggest city in the northeast. Yet, according to Pernille Ironside, UNICEF deputy representative for Nigeria, some 250,000 women give birth in the region every year. Based on global statistics, she expects that without help, around 50,000 of them will face life-threatening complications during delivery. “In the majority of these cases, death is entirely preventable,” says Ironside. “No mother, no matter where she is, should experience the tragedy of losing her child or her life while giving birth.”

These numbers aren’t just tragic misfortunes; they are powerful indicators of deep weakness in the national health system. The issue promises to play a role, albeit a limited one, in the Feb. 16 presidential election. First Lady Aisha Buhari, whose husband Muhammadu is up for re-election, has made reducing maternal and infant death one of her priorities. “When a country can’t protect its most vulnerable citizens from preventable death, it makes you question the strength of the system as a whole,” says Sanjana Bhardwaj, UNICEF- Nigeria’s chief of health.

Nigeria is trying to change the narrative in the northeast, with UNICEF’s help. Aneto, an energetic 30-year-old with rectangular glasses and a stylishly disheveled ponytail, is one of 50 midwives whom the agency has deployed since September 2017 to work in the health clinics of Borno state’s IDP camps. The midwives, mostly young women from across Nigeria, are recruited to work on a rotation basis, spending four weeks on the ground before taking one week of home leave. Aneto, who lives 770 miles away in the southeastern state of Anambra, says that she spends more time traveling to and from her rotation than she does at home on leave, but that the chance to make a difference makes it worthwhile.

So does the salary. Thanks to support from UNICEF, midwives in the program earn nearly twice as much as a senior midwife in a state hospital, and for good reason. Most of the camps are in active conflict zones and are accessible only by air. Aneto, who had never even been on a plane before her interview, was terrified when she was told she would have to commute by helicopter. Now, she says it’s as easy as taking the bus. The gunfire that frequently interrupts her sleep has been a little bit harder to get used to.

According to the U.N., Nigeria accounts for 19% of the world’s maternal deaths and nearly a tenth of all newborn deaths. The loss of so many lives is painful for Aneto to think about, especially since she knows that with a little education and the right kind of tech interventions, it wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to bring her country’s maternal death toll closer to the European rate, which at 16 per 100,000 births is around 2% of Nigeria’s rate. Life in Banki might be easier if she had 3G coverage on her cell phone, she laughs, but overall, saving lives doesn’t require advanced technology. “We just need to get women into the clinic, and get them here often.” For her, prevention starts with constant monitoring, so that potential problems can be identified and fixed before the woman even gets to the delivery table.

Nigeria’s health ministry recommends that women consult with a health care professional four times in their pregnancy. In 2016, the World Health Organization changed its recommendation from four to eight visits. Aneto wants to see her -patients at least once a month, and doesn’t mind if they come in even more often. That way she can make sure they are taking anti-malaria medications and sleeping under mosquito nets. Malaria is one of the major causes of preterm labor, uterine rupture and post-partum hemorrhaging.

In a remote area like Banki, or the dozen other IDP camps where UNICEF has medical clinics, early identification of potential problems is even more -essential, says Dr. Saidu Hassan, a Health Specialist with UNICEF in the Maiduguri Field Office. While medical evacuations are possible, military convoys to a hospital in Maiduguri can take several days to organize, especially if fighting has broken out. When it’s clear a pregnant woman will need specialized care, midwives can refer her to the capital well in advance of her due date, to avoid complications, says Hassan. But “if a woman hemorrhages in Banki and needs blood, well, she would not likely make it.” A trained midwife can not only manage labor so hemorrhages are less likely to happen, she can also identify potential problems during delivery and apply early interventions.

Aneto hasn’t even finished wiping down the bed when Halima Musa, 30, staggers into the delivery room supported by a pair of clinic assistants. Within moments the angry squall of a newborn girl—Musa’s seventh child—fills the room. Before Aneto can finish cleaning off the baby, Musa is being hustled off the table to make room for Fanna Balama, who is 15. Balama’s- baby—her first—is already crowning, and another midwife takes over. Aneto mops sweat from her face and laughs. “Sometimes we have so many women coming in here it feels like a market.”

The drive to get women out of their homes and into the clinic is already beginning to bear fruit in the northeast. The Banki clinic didn’t see a single case of maternal mortality in the 1,271 babies delivered in 2018. But women have died giving birth at home in the camp. “Delivery at home is a serious problem here,” says Kellu Dauda, a 28-year-old midwife at a clinic in Ngala, also near the border with Cameroon. “When you deliver in the clinic, we can take care of problems. If there is a tear, we have sutures. If you are bleeding, we can help. When you deliver at home, anything can go wrong.”

Around 80% of women in northeast Nigeria still deliver at home, where they have no access to the kind of care that can save lives. Many depend on the help of traditional birth attendants who, though well-meaning, can make complications in delivery worse. Often, they pull out the placenta, which can rupture the uterus, instead of waiting for it to come out on its own. Sometimes, uneducated attendants- use dirty tools to cut the umbilical cord and unwittingly give the newborn blood poisoning or tetanus. The tradition of treating the baby’s umbilical cord with cow dung doesn’t help, either.

But traditional birth attendants don’t always make traditional mistakes. Recently Hassan has noticed that several are injecting their clients with oxytocin, which can be easily found in Nigeria’s largely unregulated drugstores, in order to accelerate contractions. When it is used incorrectly, the effects can be deadly.

Rather than compete with the traditional attendants, UNICEF has started incorporating them into the camp clinics, offering them training and jobs as assistants and cleaners. They get incentives for persuading pregnant women to attend the clinics, and when those clients come back home with healthy babies, the attendants can maintain their status as trusted figures in society.

The midwives need all the help they can get. Dauda loves her work, but the conditions are hard. In the Ngala clinic, Dauda sees up to 50 pregnant women a day and is constantly on call for deliveries. There is nothing better than bringing a baby into the world, she says, but there is little worse than suturing a woman at night by the light of her cell phone because the clinic has no electricity.

The Nigerian Ministry of Health says it is committed to improving conditions for pregnant women in the northeast and in the country in general, but the need is great and resources limited in a country that already has one of the world’s worst health-worker-to-population ratios. Nigeria has only 20 doctors, nurses and midwives per 10,000 inhabitants, fewer than the 23 the WHO says is necessary to ensure “skilled care at birth to significant numbers of pregnant women.” UNICEF plans to train 5,000 midwives for deployment countrywide, but to Ironside, “it sometimes feels like a drop in the bucket. We have such a massive gap in terms of the availability of medical services generally; what it really means is that there needs to be much more government investment in health care and training in the northeast, once security is re-established.”

Alas, Boko Haram is still an ever present threat to the region. On March 1, 2018, two humanitarian workers and one UNICEF doctor were among 11 people killed in an attack by insurgents in the nearby town of Rann. A nurse and two Red Cross midwives were taken hostage. When the ransom wasn’t paid, they executed one of the midwives on Sept. 17 and another a month later. On Dec. 6, Boko Haram struck again, burning down UNICEF’s clinic in Rann. The agency has condemned the attacks and called for the protection of all humanitarian workers.

Though they shared the same -WhatsApp group, Dauda didn’t know either of the executed midwives personally. Yet despite her fears and the urging of her family, she says she won’t go anywhere. “If we are not here, what will happen to all the pregnancies? What will happen to the babies? Without our help, it will be even worse than Boko Haram.”

Correction, Feb. 7

The original version of this story misstated Dr. Saidu Hassan’s title. He is a Health Specialist with UNICEF in the Maiduguri Field Office, not an ob-gyn for UNICEF’s Maternal and Newborn Health program. It also misstated the name of a midwife seen in the final photograph. The midwife’s name is Gloria Eshiaze Gabor, not Stella Aneto.

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision