There may not even be a name for what the crown prince of Saudi Arabia has been doing in the U.S. for three weeks, but he has been doing a lot of it. By the time 32-year-old Mohammed bin Salman departs, he will have visited five states plus the District of Columbia, four Presidents, five newspapers, uncounted moguls and Oprah. America has not seen the like since Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev arrived in September 1959 in a Tupolev 114 with cracks in the fuselage to knock around the country for 13 days, putting a relatable human face on America’s most dangerous enemy.

Bin Salman’s ride is a Boeing 747 with God Bless You emblazoned under the cockpit in Arabic and English. And the kingdom he essentially rules—as iron-fisted regent of his ailing 82-year-old father, King Salman—defines frenemy. His U.S. itinerary (a week longer than Khrushchev’s) is as wide-ranging as the American distrust of his homeland: 55% of Americans disapprove of Saudi Arabia, according to the latest Gallup survey. In the 1970s, the Saudis engineered the oil embargo that had Americans waiting in gas lines; in the ’90s, U.S. troops scrambled into the desert to save the Saudis in the First Gulf War; and when American families drew up emergency safety plans in the fall of 2001, it was after the terrorist attacks orchestrated by one Saudi, Osama bin Laden, whose countrymen accounted for 15 of the 19 people who carried out the attacks. A great deal has turned on the actions of men in red checkered headscarves and flowing robes.

So there could hardly be a more disarming question than the one bin Salman poses in the hotel suite where he has just sat for a formal portrait, once the cameras are finally gone: “Can I take this stuff off?”

The instant transformation that follows—kerchief off, ceremonial robe handed to an aide—captures the entire point of his sojourn: to sell skeptical Americans on his audacious, risky plan to modernize Saudi Arabia and reassert its primacy in the Middle East. Over the course of three years since his father became king, bin Salman has ruthlessly consolidated control over the kingdom’s economic and security power centers. He has introduced modest liberalization and sharply escalated a proxy war with Iran across the region, creating a humanitarian crisis in neighboring Yemen. And he proposes to wean the kingdom off oil exports and diversify its economy for a post-petroleum future.

If it works, bin Salman’s putative revolution could transform one of world’s most retrograde autocracies from exporter of oil and terrorist ideology into a force for global progress. But sudden change often ends badly in the Middle East, and warning flags snap from the crown prince’s actions at home and abroad. “He is an ambitious young man willing to act aggressively and decisively to consolidate power,” says Chas W. Freeman Jr., a former U.S. ambassador to Riyadh under President George H.W. Bush. “[But] the rashness of much of what the crown prince has been doing—it’s pretty radical stuff—it does make him vulnerable.”

During the 75 minutes he spends with TIME at New York City’s Plaza Hotel, Saudi bombs still fall on Yemen, Saudi bloggers remain in jail and 3 out of 4 Saudi citizens still collect a paycheck from a kingdom where poorer foreigners hold 84% of real jobs. But the man in charge no longer seems of that world. Folded into a corner of the couch in a brown smock, he looks like someone you knew in college, a big guy going on about something that seems really important to him. His thinning hair is matted. He holds a Coke Zero.

The heart of the pitch the crown prince has taken on the road is forward-looking, universal and delivered in the confident, fact-stippled surge of words that might describe a startup. Bin Salman in large part is looking for money, foreign funds being a crucial element of Vision 2030, his plan that promises to reconcile feudal society with the world around it. As hard as it once would have been to imagine, collapsing oil prices, and the economic and social demands of an exploding youth population, require economic reform. And for all his power and wealth, bin Salman needs outside help to do it.

That’s partly because Saudis themselves are resistant to change. An impoverished desert wasteland a century ago, Saudi Arabia rode oil wealth through decades of change. “It’s too hard to convince them that there is something more to do,” bin Salman says of the founding generation, “because what happened in their time, in 50 or 60 years, it’s like what happened in the last 300 or 400 years in the United States of America.” But bin Salman was born into that modern world. Seven in 10 Saudis are even younger than him. And when they look up from their phones, they are less impressed. “Our eyes are focusing on what we are missing,” bin Salman says.

But it’s also because what he is proposing is potentially destabilizing. Bin Salman talks of repudiating not just the nation’s dependence on oil, but also the kingdom’s other leading export: religious fundamentalism, which has fueled al-Qaeda, the Taliban, ISIS and other Islamic terrorist groups for decades. “We believe the practice today in a few countries, among them Saudi Arabia, is not the practice of Islam,” he tells TIME. “It’s the practice of people who have hijacked Islam after 1979.”

Yet since September, the crown prince has sent dozens of nonviolent clerics and Islamic intellectuals to prison, leading current and former U.S. officials to question whether his talk of reform masks a crackdown on dissent. “More people today probably feel better about their country, particularly young people,” says a former top White House official. “But people have suffered, and the political repression has not lightened up. This is not a democratic reform.”

In the U.S., bin Salman has found some important supporters, though, including President Donald Trump and his influential son-in-law Jared Kushner. The President has not only pursued a tighter alliance with the kingdom and embraced it as a bulwark against a surging Iran; he has also invested deeply in the crown prince personally, tweeting reassurances through a string of controversies.

If White House support were enough to gain backing for his reforms, bin Salman would not have proceeded from Washington to Boston, New York City, Seattle, Silicon Valley, Beverly Hills and Dallas. The question is whether others will buy what the White House has signed on for. “Is this a savvy transaction by a young guy who knows his country has to change, but who intends to maintain strict and authoritarian control at home, or is this a transformation that will fundamentally alter the American conception of Saudi Arabia?” asks Aaron David Miller, a longtime State Department official now at the Woodrow Wilson Center. “When I was at the State Department, we prayed for a leader like this. [But] beware of wishing something you don’t really want.”

Upon the death or abdication of bin Salman’s father, the throne will skip an entire generation—hundreds of middle-aged princes—and fall to him. The crown prince is a man in a hurry. “I don’t want to waste my time,” he says. “I am young.”

The dire condition of the kingdom kindly accommodated his impatience. By 2015, when the crown reached bin Salman’s father, the Saudi oil economy was running on fumes. The price of a barrel, which Saudis had projected to remain at at least $100 a barrel, had fallen to $50, and immense cash reserves stood a few years from exhaustion. At the same time, the U.S., having edged closer to energy independence with natural gas and oil shale, no longer needed Riyadh the way it once did, and was noticeably less attentive. More worrying still, President Barack Obama, unlike other past Presidents, was willing to engage persistently with Iran, the Saudis’ chief nemesis. Iran, despite remaining a thorn in Washington’s side, was aligned with the U.S. in its desire to destroy ISIS, the Sunni extremists who executed Americans on camera and used Saudi textbooks in their schools.

Faced with this panorama, the young prince quietly but ruthlessly consolidated power in the kind of bold strokes that would have left Niccolò Machiavelli feeling bashful. At the time of King Salman’s ascension, his son was so unknown outside the kingdom that even his age was a subject of speculation (he was 29), yet the new monarch bet everything on him. He made bin Salman Defense Minister, in charge of what was then the world’s third largest military budget, after the U.S. and China, and the young prince promptly launched a war, pummeling Iran-backed rebels in Yemen. He was also named head of Aramco, the behemoth state oil company, chief of economic development and deputy crown prince.

The final title designated bin Salman as second in line for the crown, behind his 55-year-old cousin Mohammed bin Nayef, who famously survived an attack by an al-Qaeda prisoner who detonated a suicide bomb hidden inside his own rectum. But bin Nayef was no match for his cousin’s ambition. In June 2017, the king removed bin Nayef as crown prince and replaced him with bin Salman.

Five months later, bin Salman rolled the dice again, imprisoning dozens of people including princes, aides and businessmen in the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Riyadh. They were accused with corruption, though there was no formal legal process and no transparency. And at least one aide, who died in custody, showed signs of physical abuse, the New York Times reported. “He was far more powerful than people assumed and the opposition was far weaker,” says Robert Malley, a former top White House official under Obama.

Allegations of corruption have long been used as a political bludgeon in Saudi Arabia, where pilfering from the public till has often been synonymous with royalty. In 2001, Prince Bandar al-Sultan publicly estimated that $50 billion had been transferred to royals’ private accounts since the kingdom’s founding. Bin Salman’s government claimed to recover twice that amount from its captives, but he hasn’t been shy about his own spending. He paid more than half a billion dollars for a yacht and $300 million for a gold-encrusted château near Versailles, all with money that he insists he earned on his own. “If I’m corrupted, please show me the proof,” he says. “It is well known that King Salman and his sons and his team, they are super clean. Everyone in Saudi Arabia knows that.”

Whether shakedown or rough justice, the Ritz episode eliminated his chief political rivals and cemented his power. “It was a kind of coup d’état—a bloodless coup d’état—of the old system,” says former ambassador Freeman. But it also had the effect of rattling investor faith in the kingdom’s stability. “All power that had been distributed under the previous constitutional arrangement very widely under a checks-and-balances arrangement has been compressed and concentrated into the hands of one man,” says Freeman.

That in turn undercut bin Salman’s revamp of Saudi Arabia’s economy, society and world status—all the things he came to the U.S. to promote. Bin Salman’s Vision 2030 plan calls for establishing a $2 trillion sovereign wealth fund, the world’s largest. Half, he says, would be invested inside the kingdom—he talks enthusiastically about the future of carbon fiber and plans to make Saudi Arabia the world leader in solar energy—and half in enterprises abroad. He also wants to partially privatize Saudi Aramco in what would likely be the largest initial public offering in history. But after the Ritz, the IPO came off the calendar and the U.S. tour went on.

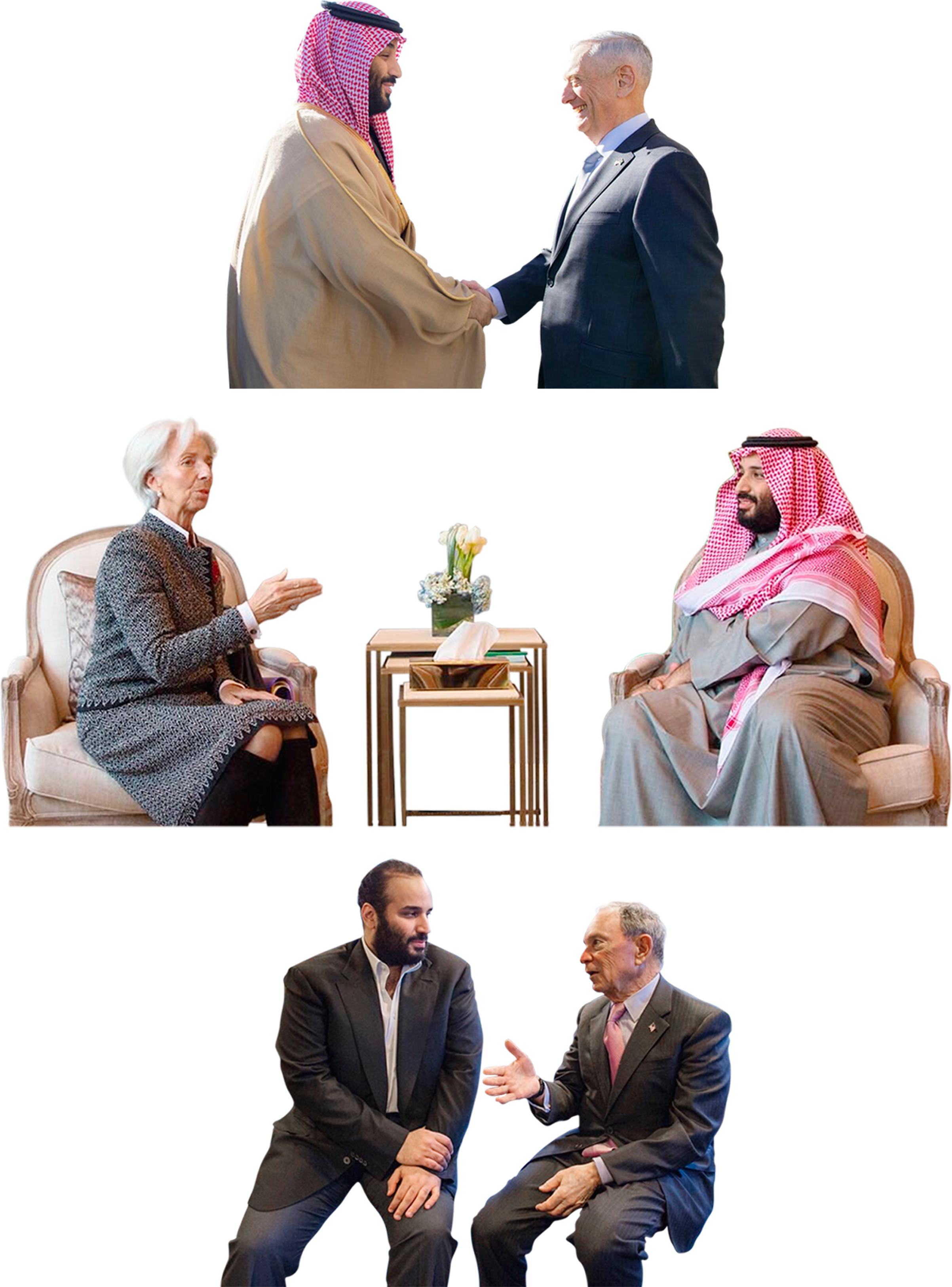

In Manhattan, the crown prince hit Starbucks with former mayor and billionaire Michael Bloomberg. He wore a blazer and a shirt open at the collar. It was full regalia at MIT, but a business suit in Seattle for Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates. Clothes may not make the man, but if your message is modernity and flexibility, they say more than “reformer,” a label blanched of meaning by its application to a parade of more traditional Saudi royals. And bin Salman has turned heads. “No one has said what he has been saying in the entire history of the kingdom,” says Bilal Y. Saab, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute. “It’s significant.”

Bin Salman has made some concrete changes. In June, women will drive on Saudi roads, independent from male chaperones. Music festivals and movie theaters are opening, though questions remain about separate seating for men and women. The kingdom’s religious police are being reined in. In a setting as sterile and controlled as Saudi Arabia, these modest changes have generated genuine enthusiasm among activists, many of whom had been skeptical of bin Salman.

The crown prince says the kingdom has to be sufficiently “livable” both to satisfy young Saudis and to attract foreigners to work there. He also hopes to draw tourists, and announced on April 2 that the kingdom will relax visas for them. “I believe in the last three years, Saudi Arabia did more than in the last 30 years,” bin Salman says.

But the crown prince also fits into a larger global trend: authoritarianism. Bin Salman has taken even greater control of the Saudi media, and, in the judgment of members of a U.N. panel, has “arbitrarily” imprisoned 60 activists, journalists, academics and clerics since September. Saudi Arabia remains an absolute monarchy, the crown prince notes, adding that he has no plans to dilute his power in the coming 50 years that he might rule. “What we should focus on is the end, not the means,” he says. “If the means are taking us to that end, that good end, and everyone agrees on it, it will be good.” Bin Salman says he ultimately wants freedom of speech, improved employment, economic growth, security and stability for Saudi Arabia. And he says his absolutist approach is a better means to get it than the chaos that followed the Arab Spring elsewhere in the region.

The problem for Saudi Arabia, the region and the world is that the means are wreaking havoc in the meantime. In the name of standing up to Iran, bin Salman launched a 2015 air war in Yemen that has cost more than 10,000 lives, and devastated what was already the poorest country in the Arab world. Of the 16,749 bombing runs recorded since 2015 by the Yemen Data Project, an independent human-rights monitoring group, nearly a third targeted nonmilitary sites. “You are waiting to die if you are here,” says Radhya Almutawakel of the Yemeni nonprofit Mwatana Organization for Human Rights, speaking by phone from Sana’a, the capital. The U.N. calls it “the worst man-made humanitarian disaster of our time.”

Bin Salman remains resolute. Although he told TIME he does not rule out sending ground troops, his priority is that the war remain painless for Saudis. “We want to be assured that whatever happens, the Saudi people shouldn’t feel it,” he says. “The economy shouldn’t be harmed or even feel it. So we are trying to be sure that we are far away from whatever escalation happens.” The White House so far is happy to play a supporting role in the Yemen war, providing intelligence, midair refueling and billions of dollars of munitions.

For decades, “stability” was what the U.S. expected Saudi Arabia to provide in the Middle East. But if anything the rapprochement with the White House has emboldened the new regime. Shortly after Trump departed Riyadh from his first foreign visit last May, the Saudis stunned the world by launching a blockade on Qatar. In November, bin Salman appeared to make a hostage of Lebanon’s Prime Minister Saad Hariri for more than two weeks, after Hariri announced his resignation in a late-night video during a trip to Riyadh. Amid regional and global uproar, the Lebanese leader returned to Beirut and recanted his resignation days later.

The ultimate target in all these adventures was Iran, which arms the largely Shi‘ite Houthis in Yemen, has warm relations with Qatar and plays a central role in Lebanese politics. It is also the great rival of Saudi Arabia both for regional power and leadership of the Muslim world. Bin Salman calls Iran the source of every ill in the Middle East—including, to many scholars’ astonishment, religious extremism in Saudi Arabia. The crown prince dates this extremism to 1979, the year Sunni radicals stormed the holiest site in Islam, the Grand Mosque at Mecca, and called for the overthrow of the House of Saud on the grounds of insufficient piety. In bin Salman’s improbable telling, the zealots were inspired by the Islamic revolution that had installed a theocracy in Iran a few months earlier.

Whatever the cause, the result was catastrophic. Cowed by the accusation of impiety, the House of Saud, already long-dependent on religious conservatives for moral authority in the country, gave them a freer hand. The result was a Muslim fundamentalism that coincided with yet another fateful event of 1979: the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In confronting that Cold War threat, the U.S. made what turned out to be a shortsighted move: fighting the Russians by encouraging Muslims to embrace a war against the infidels. In that milieu, al-Qaeda came into being.

Historians note that Saudi Arabia itself was founded on a similar bargain. In the 18th century, the very first Saudi king struck a pact to get the services of the fanatical fighters who followed Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab. The allies agreed that the House of Saud would govern the temporal kingdom, but spiritual life would be the province of the severe brand of Islam named for its founder.

Bin Salman claims the severity is overstated: “What Wahhabist?” he asks, smiling. Wahhabism is universal shorthand for the unforgiving brand of Islam that millions of foreign workers have learned in Gulf mosques, and that Saudi Arabia’s ministry of Islam has exported abroad. Bin Salman quibbles. “First of all, Saudi doesn’t spread any extremist ideology,” he insists. “Saudi Arabia is the biggest victim of extremist ideology.“

Bin Salman says his government is intent on undoing lessons taught by extremists, and says he has Islamic doctrine on his side. “If someone comes and says women cannot participate in sport,” he says, “The Prophet, he raced with his wife. If someone comes and says women cannot do business, the wife of the Prophet, she was a businesswoman, and he used to work for her as Prophet. So the Prophet’s practice is on our side.”

The kingdom is also softening its public posture toward Israel, acknowledging an alignment against Iran that has existed discreetly for years in the realms of intelligence and back-channel diplomacy. “We have a common enemy, and it seems that we have a lot of potential areas to have economic cooperation,” the crown prince tells TIME. “We cannot have relations with Israel before solving the peace issue with the Palestinians because both of them they have the right to live and coexist,” he says, but “when it happens, of course next day we’ll have good and normal relation with Israel and it will be in the best for everyone.”

All this adds up to a different Saudi Arabia, one way or another.

To outsiders, the most obvious danger is from bin Salman’s impulsiveness in foreign policy. The running war in Yemen is the most worrisome example. “This was a somewhat immature, ill-advised and improvised action,” says Stephen Seche, former U.S. ambassador to Yemen, that “raises questions about whether he can carry out other very ambitious plans.”

The challenge is to reconcile that, and the iron fist he shows rivals at home, with the charming fellow flying around the U.S. For all the contradictions, few come away from an encounter with bin Salman unaware of the force of his personality, intellect and devotion to change.

“He really is trying to project a certain image, and he’s worked on it extremely hard,” says Saab. It is more than enough to give hope to those who want to see the possibility of positive disruption in the Middle East. Says the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Miller: “I guarantee you that people who this man has sat down with are asking themselves: What’s new in the Middle East? Two words: Saudi Arabia.”

— With reporting by Haley Sweetland Edwards, Edward Felsenthal and W.J. Hennigan/New York and Philip Elliott/Washington

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time