A watch ticked on a dead man’s wrist. Another man looking at the body joked, “I guess it sure does take a licking but keep on ticking!” Humor was critical in the situation. The men and women said at the time that a joke, no matter how bad, helped break the tension of their overwhelming task: the recovery of hundreds of dead U.S. citizens from a sweltering Guyanese jungle.

It may seem heartless or ghoulish to joke as hundreds lay dead before you but facing the largest such loss of civilian American lives pre-9/11, humor was just one form of self-preservation.

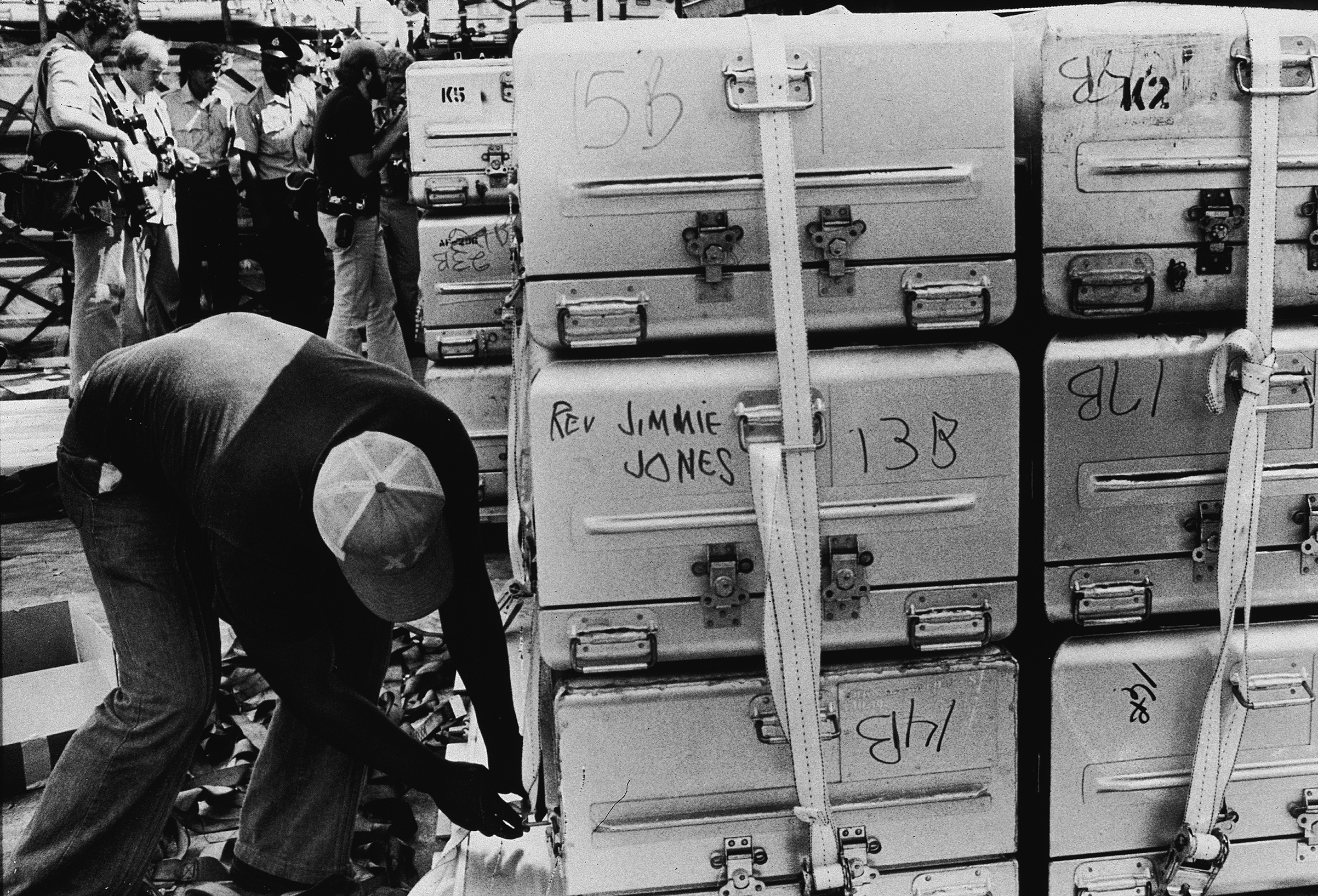

On Nov. 18, 1978 — willingly or unwillingly — the followers of the charismatic Pentecostal leader Jim Jones drank cyanide-laced fruit punch. Over 300 children were made to drink it, and syringes full of the mixture were emptied into infants’ mouths. Those who didn’t join Jones’ so-called “revolutionary suicide” were injected with poison; others tried to run for the surrounding jungle only to be shot by one of Jones’ armed guards. All told, 918 people died that day.

The U.S. tried to have the bodies interred on site, offering to foot the bill for the Guyanese government. But the Guyanese government wanted no part in the burial, and families of the dead wanted their loved ones returned. The military was the only organization able to handle mass casualty recovery and Dover Air Force Base in Delaware was assigned receipt of the dead. What happened there in the aftermath would become one of the first records of how deeply first responders can be affected by the trauma to which their jobs expose them.

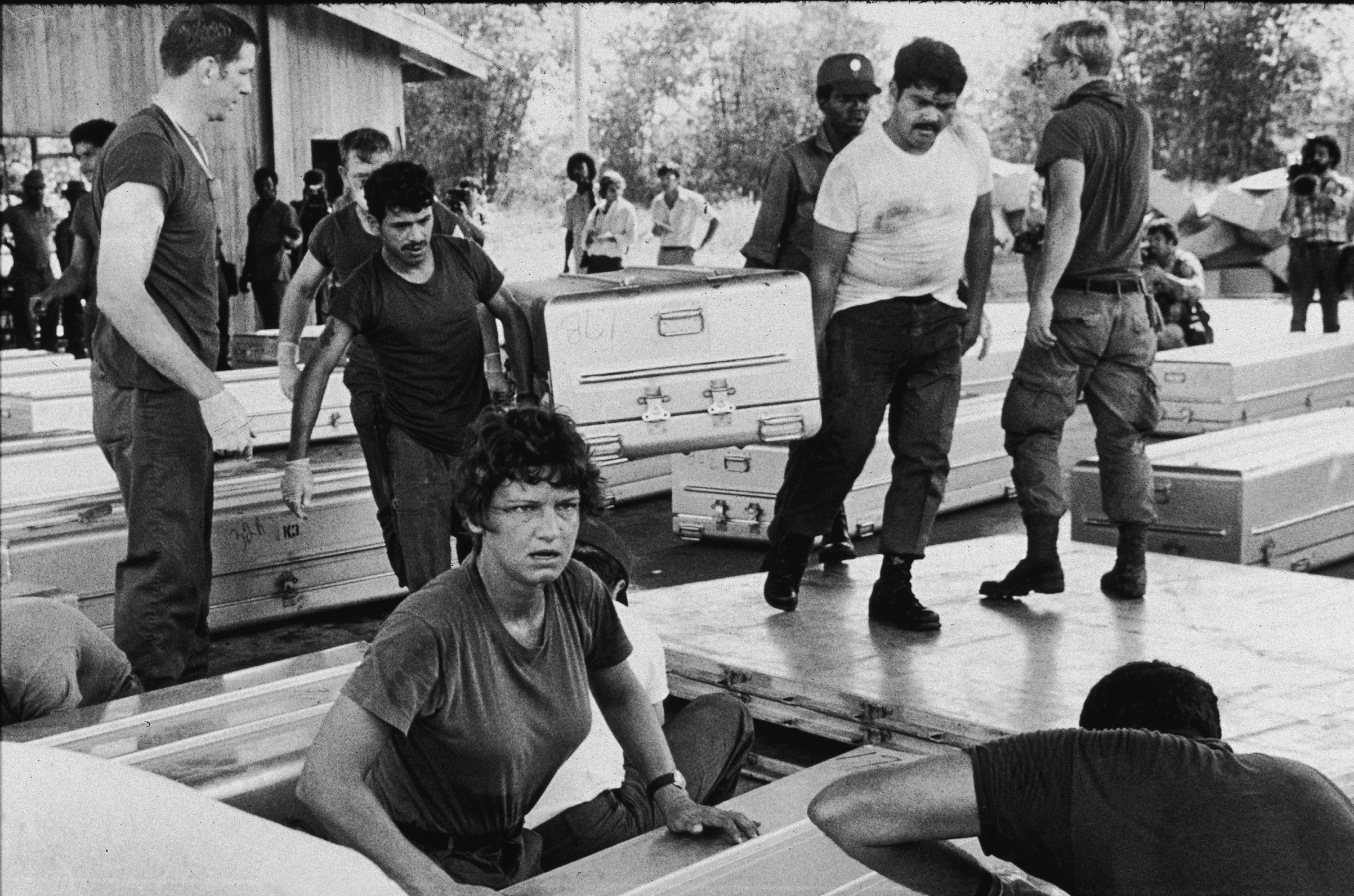

Loaded with waterproof canvas body bags and coffin-like metal transport containers, U.S. military helicopters shuttled the dead and recovery personnel alike between Guyana’s capital and Jonestown, isolated deep in the jungle.

Recovery workers would later report that the staggering number of children they saw there was the most disturbing thing they encountered. “Can’t sleep,” reported one worker. “Cannot get the small children out of my mind.”

Society’s understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder was limited in 1978 and associated almost exclusively with wartime experiences, falling under the umbrella of what was often thought of as “shell shock.” Even less was known about the impact a mass casualty recovery mission would have on first responders. A smattering of studies had been done by the military on nurses, for example, but the literature was sparse.

Jonestown was different. It involved the deaths of civilians and demanded the involvement of a cross-section of workers, from doctors and pathologists to typists and the yeomen who cleaned the transport containers.

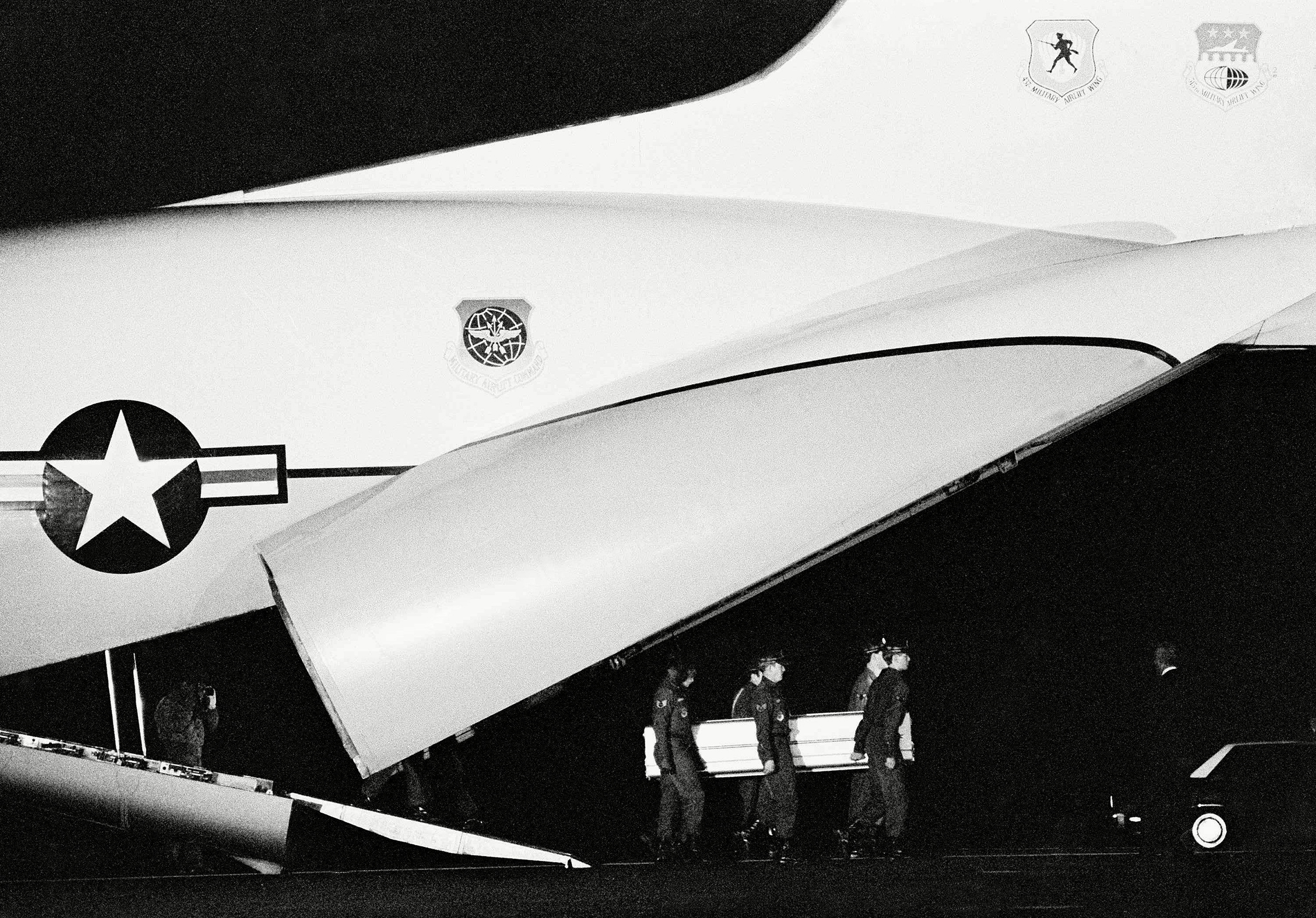

When the first C-141 aircraft touched down at Dover on Nov. 23, 1978, it carried the remains of 40 U.S. civilians. The magnitude of the situation was still unknown — and grossly underestimated. So was the emotional impact it would have on those left to deal with it.

Read more: See TIME’s original report on the massacre

‘Beyond Imagination’

Jim Jones had become a popular Pentecostal preacher in the 1960s, using a gospel of social justice and inclusion to attract followers to his San Francisco-based congregation, the People’s Temple. The hundred or so followers he’d brought West from his home in Indiana soon ballooned to a thousand, even as his paranoia likewise grew, fed by his growing dependency on pills. Jones staged fake faith healings to draw more people to his church and consolidate his power with only a small circle of trusted faithful. He began referring to himself as God.

But in 1977, with a damning article about abuses within the Temple about to break, Jones and nearly a thousand of his followers fled to land the Temple had previously purchased in Guyana.

Less than a year later, most of them would be dead. The bodies that would need to be brought back totaled more than 900.

Those bodies were taken to the base mortuary for identification and in some cases autopsy; the remains would eventually be stored on base in Hangar 1301.

At the time, Patricia Edwards had worked for seven years as a civilian employee at Dover AFB, where she still is until today. Now working in the Airman and Family Readiness Center, back then Edwards’ job was to manage logistics.

“I had to recruit individuals that would work in the mortuary environment and to make sure that there was enough staff and administrators to handle the Jonestown situation,” she told me.

“I found out about Jonestown like everyone else did back then, through the media,” she said. It was from those reports that Edwards and her colleagues found out just how much of a job they would have to do, and quickly. “What would normally take about two to three weeks had to be done in one,” Edwards said.

The base needed more people. Not just trained mortuary staff but ancillary support staff. Tents were needed for food-service workers, administrative staff and a legion of typists. Edwards notes that this was before computers, so every request had to be typed up and every person coming onto the base had to be processed and credentialed individually. Basically, she said, a base within the base had to be assembled.

Eventually the Air Force did a study on the impact the recovery had on personnel military and civilians alike. The study was simple as there were no analogs to build from and a dearth of information on the emotional impact on recovery workers or “secondary disaster victims.” Its results, however, offer a glimpse at just how complex the issue is. The findings based on the recover effort at Jonestown and Dover — which are now posted on the Defense Technical Information Center website, a searchable database dedicated to aggregating military scientific and technological data — live on in articles, disaster recovery textbooks and military training guides.

“It is difficult to convey to someone,” the authors wrote in the preface of the study, “What a week in a tropical environment can do to a [dead] human body.”

The conditions at Jonestown were compounded by rain and staggering humidity. Bodies bloat and change color and are infested by insects. Above all, the authors write, “the overpowering and unforgettable odor of just one body [are] beyond imagination.”

The study asked first basic questions about age, race, marital status and whether military or civilian. Respondents were asked if they had any exposure to human remains: none, saw bodies in containers with no odor, odor only, handled containers, handled body bags or handled human remains directly.

The immediate emotional impact was what you would imagine; seeing “three or four babies per [body] bag” kept workers up nights. Some were angry the military was involved in recovering “fanatics’” bodies at all. Some reported personal growth from the experience, one person realizing as human beings “you’ve got to give a damn.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

What’s Remembered

By April of 1979, more than 300 bodies of those followers had been claimed by family members. But at Dover AFB, over 500 remained unclaimed and over 200 were decomposed past the point of identification. Many relatives couldn’t afford the military’s transport fees — nearly $500 — for a family to bring home a loved one for private burial.

Even if they could have, no cemetery wanted the remains. Communities didn’t want to become pilgrimage sites for Jones’ remaining U.S. followers, and draw unwanted attention — and people — to their town. Eventually, a cemetery in Oakland, across the bay from the Temple’s former home in San Francisco, agreed to inter the remains of hundreds of the Jonestown dead.

Forty years on, there is a memorial to the victims of Jonestown in Oakland. Commemorative events are scheduled where survivors and family can gather and mourn. More is understood about the people of Jonestown, that they were overwhelmingly victims.

And almost everything has changed at Dover. The only remaining building from the Jonestown time period is Hangar 1301. It is now the Air Mobility and Command Museum, dedicated to the history of “airlifts and air refueling” the place where old airplanes go if they are lucky.

Patricia Edwards is still there, assisting military families through Dover’s readiness and resilience program. But Jonestown is never far away, she said. The experience of dealing with the bodies shared by people working at the base, in the mortuary and the tent city created an extended family, and that feeling endures too.

One other inescapable thing stays with her. “The stench.” She says, “I will never forget the stench.”

Andy Kopsa is a reporter based in New York City.

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time