The crowds weren’t just equipped for a storm, they were counting on one. When rain started to fall on the tens of thousands of mostly young people amassed around Hong Kong’s legislature on the morning of June 12, umbrellas popped open with loud shouts of “Ga yau!” — a Cantonese cheer meaning “Add oil,” as to a fire. Within hours, the flimsy canopies were flipped sideways and turned into makeshift shields against tear gas and pepper spray fired by local police. They proved less reliable against rubber bullets, however, and might offer no protection at all against the authoritarian forces that loom over the entire island.

But the point was to try.

The protests were hardly the first in the former British colony since it was handed over to China in 1997. The specter of greater control by communist authorities on the mainland had driven Hong Kongers onto the streets in 2003, 2012 and 2014. But this time, the numbers were greater than ever before and the escalation carried at least the sense of a showdown.

The specific issue at hand was a bill that would allow the extradition of fugitives to stand trial in mainland China. The legislation, fast-tracked by the city’s leadership, is widely seen as a threat to the unique freedoms this city of 7 million enjoys. Under the terms of the handover, Hong Kong has operated under a customized model called “one country, two systems,” which gave it a 50-year period of effective self-rule, even though it is part of China. Its history as a lucrative colonial port town left a liberal legacy unique in the People’s Republic.

Hong Kongers have long lived a freer, more cosmopolitan lifestyle than most Chinese, and prejudice against mainlanders is pervasive. Free speech and an independent press are enshrined in the Basic Law that has governed the city since the handover. They’re proud of their distinct cuisine and language, speaking Cantonese rather than the Mandarin more common in greater China.

But critics fear that China’s encroachment may bring an end to all that. Beijing might use the law to nab opponents and submit them to its notoriously opaque justice system, they say. The risk could extend beyond residents, even to visitors who pass through the city’s transit hub. “If Hong Kong’s extradition bill becomes law,” says Sean King, a former U.S. diplomat in Asia and currently senior vice president for the consultancy firm Park Strategies, “I’d think very carefully about visiting again anytime soon.”

In other words, the contest for Hong Kong reflects the stakes for the larger world that China seeks to lead.

The rise of Beijing has been the major global story of the new century. But the very breadth of that ascent and the bland labels of the areas where it has edged toward dominance — trade, infrastructure, finance, tech — have served to mask the nature of the system China brings with it. That system is control.

On the mainland, the system appears to go unchallenged, because control is almost total and cast as conformity. Along with a surveillance state, China’s Communist Party has worked to impose a singular vision of Chinese identity in territories where diversity once thrived. In the far western province of Xinjiang, authorities have detained more than a million ethnic Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in concentration camps where they are forced to adopt secular Chinese customs. In Tibet, the party is systematically erasing a rich Buddhist heritage. President Xi Jinping has revived nationalism as a unifying force, in step with a rising tide of authoritarians around the globe that U.S. President Donald Trump has in many cases embraced.

Now it appears to be Hong Kong’s turn to feel the heat of a greater power forcing it into conformity — but China’s freest city won’t give in without a fight. Hong Kong has a long history of mass demonstrations. Significantly, just days before the protests erupted, it was host to one of the largest-ever vigils for the victims of Beijing’s bloody 1989 crackdown on democracy activists at Tiananmen Square. It’s the only place on Chinese soil where the massacre is openly commemorated, while government censors try to wipe it from mainland memory. The spirit of the protests snuffed out 30 years before helped inflame the demonstrations seen in Hong Kong.

“We’re furious, we’re angry, some of us are afraid — but we’re here anyway,” says Laurie Wen, a 48-year-old writer who joined this month’s protests. “The thing that infuriates us the most is pointing to the sky during the day and calling it night.”

Hong Kong’s fresh wave of civil disobedience began with a murder. In February 2018, a pregnant 20-year-old woman from Hong Kong was killed by her boyfriend during a trip to Taiwan. The suspect, Chan Tong-kai, then 19, flew back to Hong Kong and has since been jailed for lesser crimes. Unable to prosecute the Hong Kong resident for a murder beyond the city’s jurisdiction and without legal grounds to send him to Taiwan, the city’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, pushed for a bill that would allow Chan to be extradited.

But the legislation raised alarm bells. Hong Kong’s courts and Lam would have the authority to transfer suspects to jurisdictions with which the territory has no extradition agreement — not just Taiwan but also mainland China. This presents a threat not just to criminals but potentially to anyone whose behavior offends the Communist Party leadership, from human-rights advocates to business executives.

That helps explain why an unusually diverse assemblage of lawyers, students, stay-at-home moms, business-people and others joined the protests against what they see as an existential assault on their rights. On Sunday, June 9, a two-mile stretch of a central avenue was filled with column after column of protesters in a uniform of plain white T-shirts. From above, the mass of slow-moving city dwellers looked like a giant snake sliding through a forest of skyscrapers and wrapping its jaws around Hong Kong’s legislative headquarters.

If the estimates are even close to accurate, the march was the largest protest in the city’s history; organizers say more than a million people — one-seventh of the population — flooded the streets with chants of “No extradition to China!” and “Carrie Lam, step down!”

The reality is, China already feels empowered to grab its adversaries from Hong Kong soil. In 2015, five book-sellers peddling salacious volumes about mainland politics disappeared; all five eventually resurfaced in China. In 2017, a Chinese tycoon was abducted by secret police from one of the city’s luxury hotels. But the extradition bill would render what are now noteworthy exceptions into something entirely routine; if the option to legally extradite people is on the table, Beijing will use it, critics say.

Chinese officials have spoken out in full support of the legislation, but Lam steadfastly denies that the amendments were Beijing’s idea. “This bill was not initiated by the central people’s government. I have not received any instruction or mandate from Beijing,” Lam told reporters at a press conference on June 10. “We were doing it, and we are still doing it, out of our clear conscience and our commitment to Hong Kong.”

Though Lam’s critics describe her as a “puppet” of the mainland, her protests illustrate the importance of maintaining at least the pretense of independence. The Hong Kong government is still haunted by the massive protests of 2003, which forced it to back down on national-security legislation outlawing sedition and criticism of the Chinese government. Scrapping the bill was perceived as an admission that the government knew it was wrong, and Lam is fearful a repeat would destroy both Beijing’s trust in her loyalty and her legitimacy at home. The last time Hong Kongers took to the street in great numbers, in the 2014 student-led occupation of the financial district that became known as the Umbrella Movement, the authorities here and in Beijing refused to grant concessions. Many student leaders were jailed, and some remain behind bars. If Lam gives in now, Hong Kong will have proved that throngs in the street still have currency in the final free enclave of China.

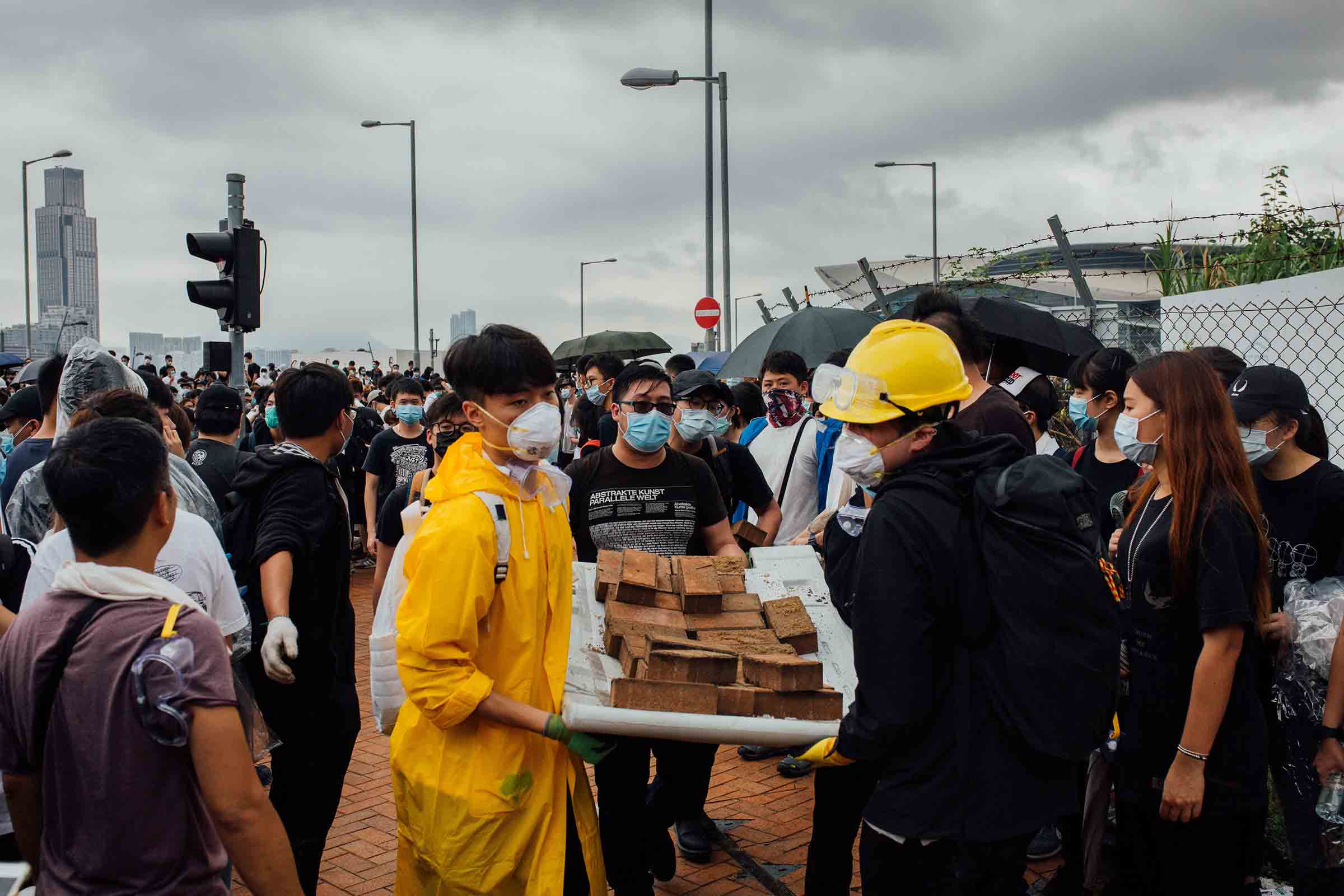

This time, unlike in 2014, the protests have taken on a more violent tenor. On the streets, clashes broke out after some demonstrators hurled bricks and bottles at police. The first clouds of tear gas exploded into the crowds just before 4 p.m. on June 12, sending panicked protesters and journalists fleeing for the safety of malls and parking garages. But the demonstrators are defiant, vowing to defy the government until the legislation is dead in the water.

The business and diplomatic communities have answered the call to support them. More than 100 local businesses committed to joining a labor strike on June 12 — an extremely rare event in Hong Kong — fearing the law could even endanger investors and government employees transiting through Hong Kong.

The government has already shown itself willing to punish private companies for offending Beijing; last year, Financial Times journalist Victor Mallet was denied a working visa after chairing a talk by a pro-independence activist.

Protest leaders have shown no sign of backing down. “We ask everyone to continue staying here to support the demonstration,” Claudia Mo, a lawmaker with the pro-democracy Civic Party yelled to cheering crowds shortly before they were dispersed. “During Occupy Central in 2014, we said, ‘We will be back.’ Today, we say, ‘We are back!’”

Read more: ‘Hong Kong Was My Refuge, Now Its Freedom Is at Stake’

The rift between Beijing and Hong Kong has now been widening for 22 years, and every attempt by the central government to bring Hong Kong further into its fold has triggered panic and protest. This in turn has deepened Beijing’s distrust of Hong Kong, which it sees as disloyal and subject to foreign interference.

News about the latest protests is being heavily censored in China, where state-controlled newspapers have blamed the unrest on “foreign forces” meddling in Hong Kong’s affairs — but experts say it is China’s own interference that may be further alienating its rogue territory.

“By forcing the issue in such an aggressive and abrupt way,” says James Millward, a professor of history at Georgetown University, “China can actually be creating a population in Hong Kong that will dig in and actually redefine itself in opposition to the mainland even more than it has so far.”

That risks putting the two sides on a more overt collision course. At best, more sustained opposition to Beijing will lead to political deadlock. At worst, it could lead to punishment in whatever form it deems fit.

Beijing’s tolerance of Hong Kong ultimately comes down to a cost-benefit analysis, and the city may be becoming more trouble than it’s worth. In 1993, four years before the handover, the coastal enclave was China’s cash cow — a financial gateway between East and West. At the time, the city accounted for roughly 27% of China’s GDP. But 26 years later, the mainland is awash in mercantile centers made in its own image and Hong Kong accounts for only about 2.9% of the Chinese economy.

“Uncomfortably for Hong Kongers, and everyone who loves Hong Kong, the city finds itself on the front lines of a global battle between a resurgent Chinese Communist Party and a world that adheres to liberal democratic values,” says Ben Bland, director of the Southeast Asia Project at the Lowy Institute and author of Generation HK: Seeking Identity in China’s Shadow. “The systems maintained by these two blocs are incompatible when pressed up against each other.”

Hong Kong’s freedoms currently allow it to fight back in ways that other parts of China can’t, but for how long? The state is becoming only more pervasive. -Xinjiang is seen by many as a laboratory for wider application of invasive surveillance. Human-rights groups have reported police methods for harvesting data from Xinjiang residents from phones and ID cards and using it to track and detain supposed threats to public order. “Many people think that Hong Kong may be the next place where it gets rolled out,” says Millward of Georgetown. In the meantime, the memory of Tiananmen — where public protest was ultimately met with tanks and fusillades — is as vivid as it is chilling in Hong Kong.

Like many youths who joined the latest protests, high school student Rachel Liu grew up in a political state scheduled to expire within her lifetime. At 15 years old, she’s tasted the freedom that Hong Kong offers and is afraid of the change an increasingly authoritarian Beijing will bring to the only home she knows. “There are so many officials in China, and they have so much power,” she said. “Even if this amendment doesn’t pass, there will be other amendments, other laws in the future that will bring Hong Kong more and more under China’s control. There’s nothing more important than this movement right now.” — With reporting by Laignee Barron, Aria Chen, Amy Gunia, Abhishyant Kidangoor and Hillary Leung/Hong Kong and Charlie Campbell/Shanghai

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time