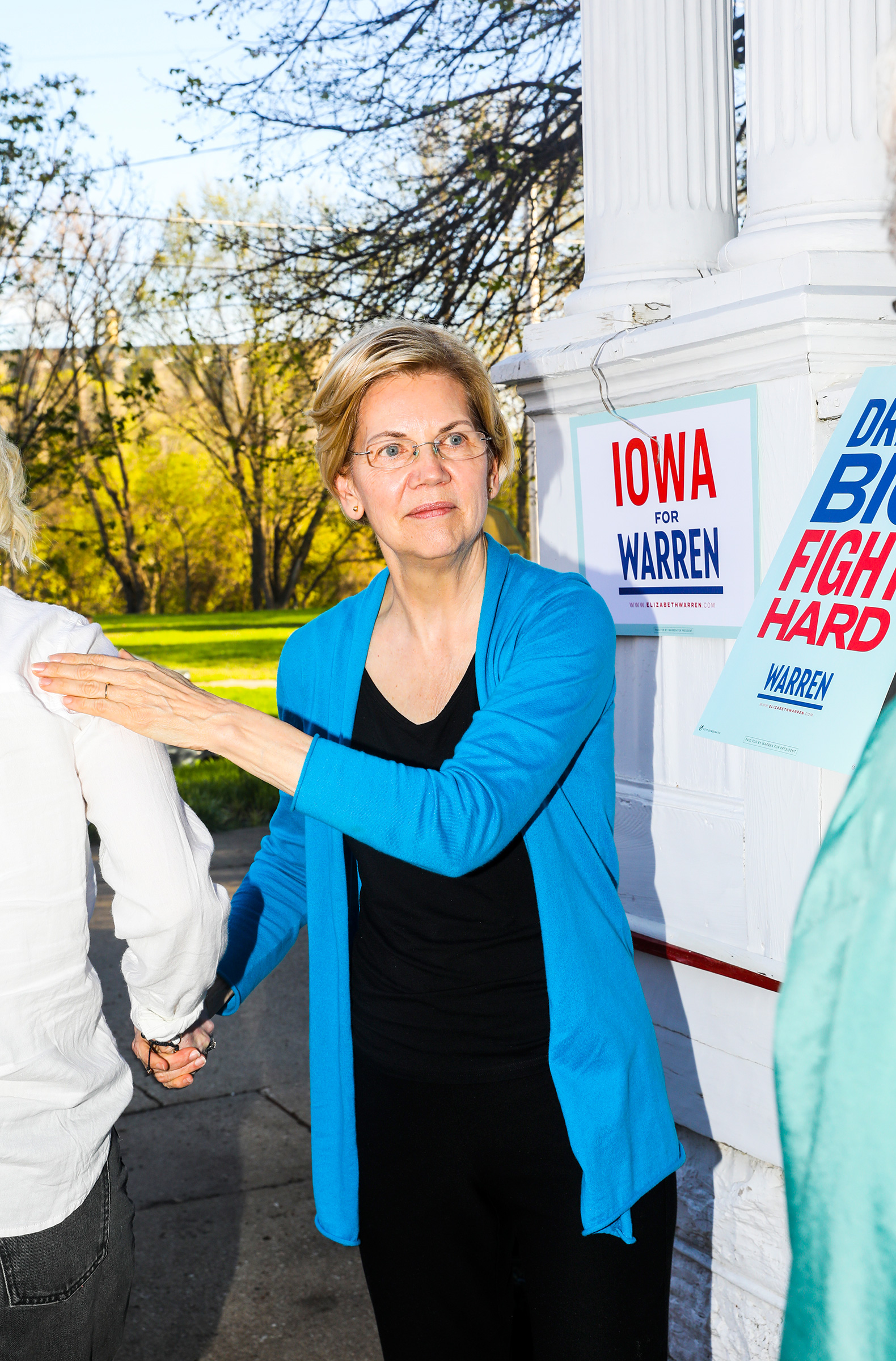

Voters encountering Elizabeth Warren on the presidential campaign trail these days often seem surprised. After a packed gathering at an elementary school in Concord, N.H., in April, a 40-something woman told me she had expected Warren to be more like Hillary Clinton but found them miles apart.

A college student who caught Warren’s speech in Hanover said he was perplexed to learn that a woman once described by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s political director as a “threat to free enterprise” in fact believes in entrepreneurship and markets. And at an event in a Portsmouth high school cafeteria, a retired teacher told me he’d heard Warren was a “Ted Cruz–like partisan” but instead found her charming. “She seems like a real doll,” he shrugged. “Can I say that?”

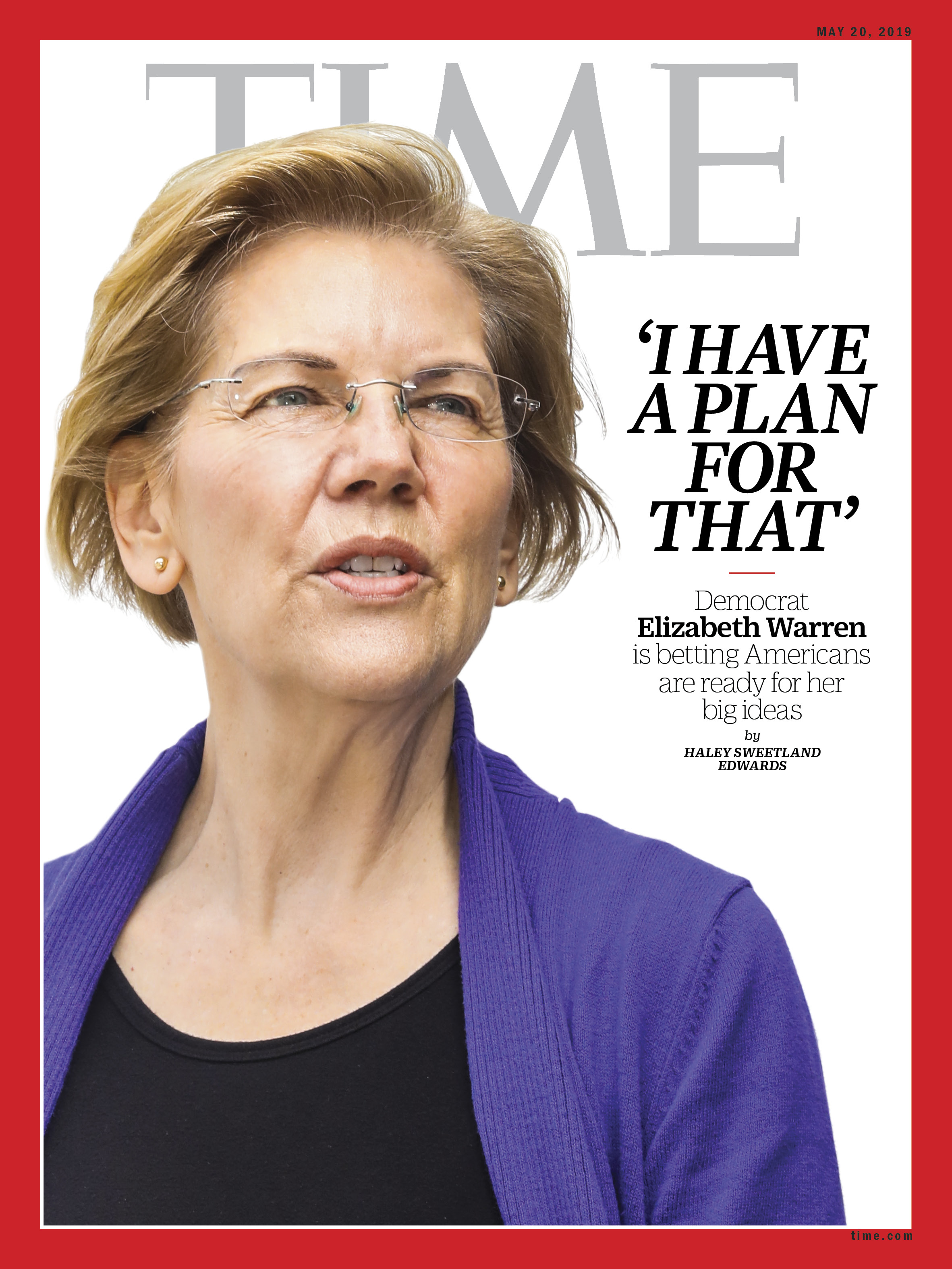

Warren first rose to fame for her withering interrogations of miscreant bankers and evasive government officials during the financial crisis 10 years ago. Since then, powerful critics in the Republican Party, as well as her own, have painted her as too liberal, too divisive, too wonky, too “strident”—that freighted euphemism so often applied to assertive women. So when I sat down with the Massachusetts Senator on a recent Tuesday, in a windowless office in Washington, I shared those voters’ surprise.

As we spoke, Warren danced in her seat, talked effusively about her family and offered a series of funny extended political metaphors borrowed from HBO’s Game of Thrones. At one point, as I struggled to formulate a question, she intuited what I was trying to ask and, conveying her readiness, extended her hands, locked her elbows and began gently flapping her arms like a bird preparing to take off in high winds.

“O.K., O.K., I can answer this,” she said.

Which might as well be a motto for Warren’s presidential campaign. She has set herself apart in a Democratic field of more than 20 candidates by offering more than a dozen complex policy proposals designed to address an array of problems, from unaffordable housing and child care to the overwhelming burden of student debt. Her anticorruption initiative would target the Washington swamp, and her antitrust measures would transform Silicon Valley. On May 8 she unveiled a $100 billion plan to fight the opioid crisis. This flurry of white papers, often rendered in fine detail, appears to suggest a technocratic approach to governing. But in fact, her vision, taken as a whole, is closer to a populist political revolution.

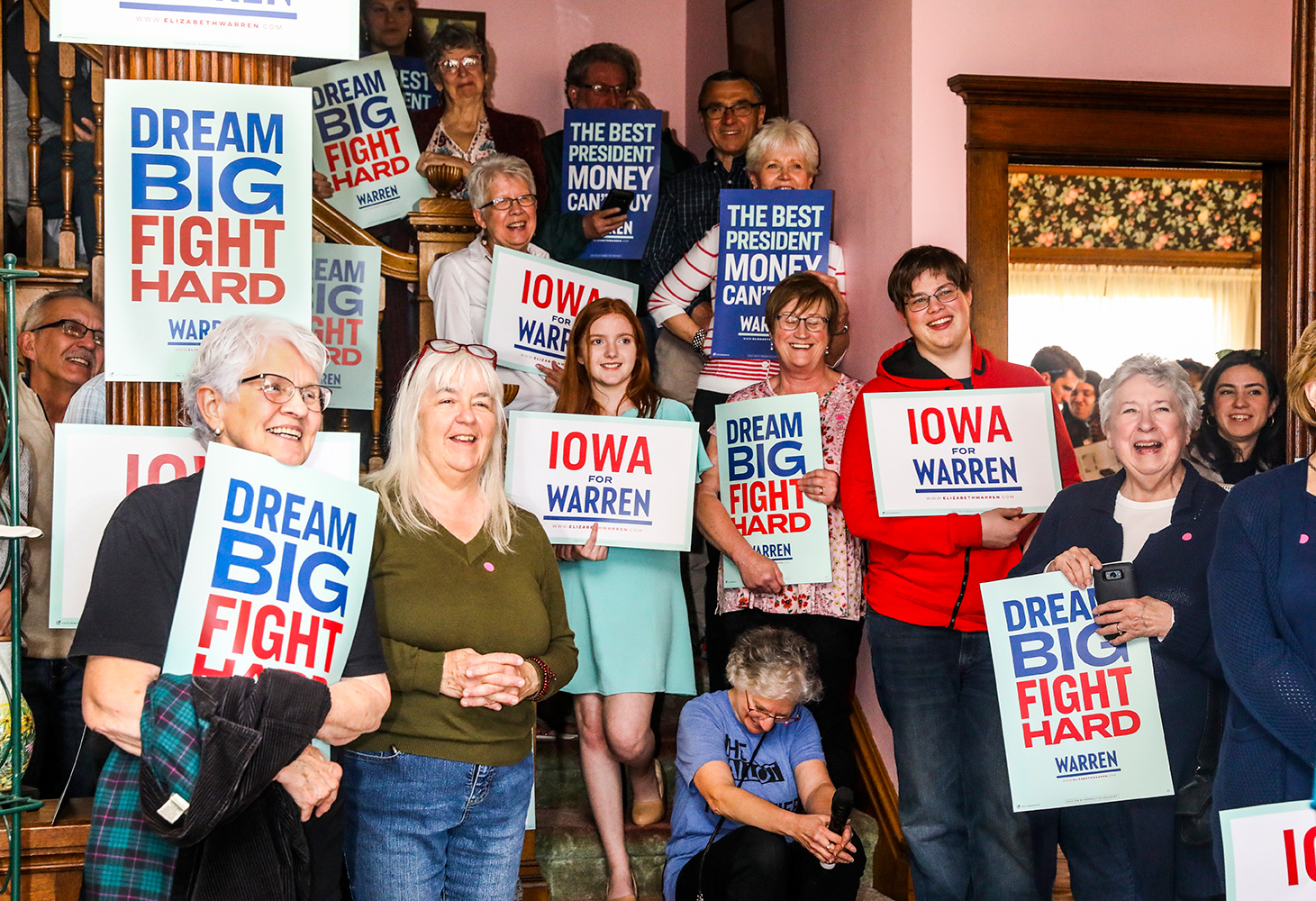

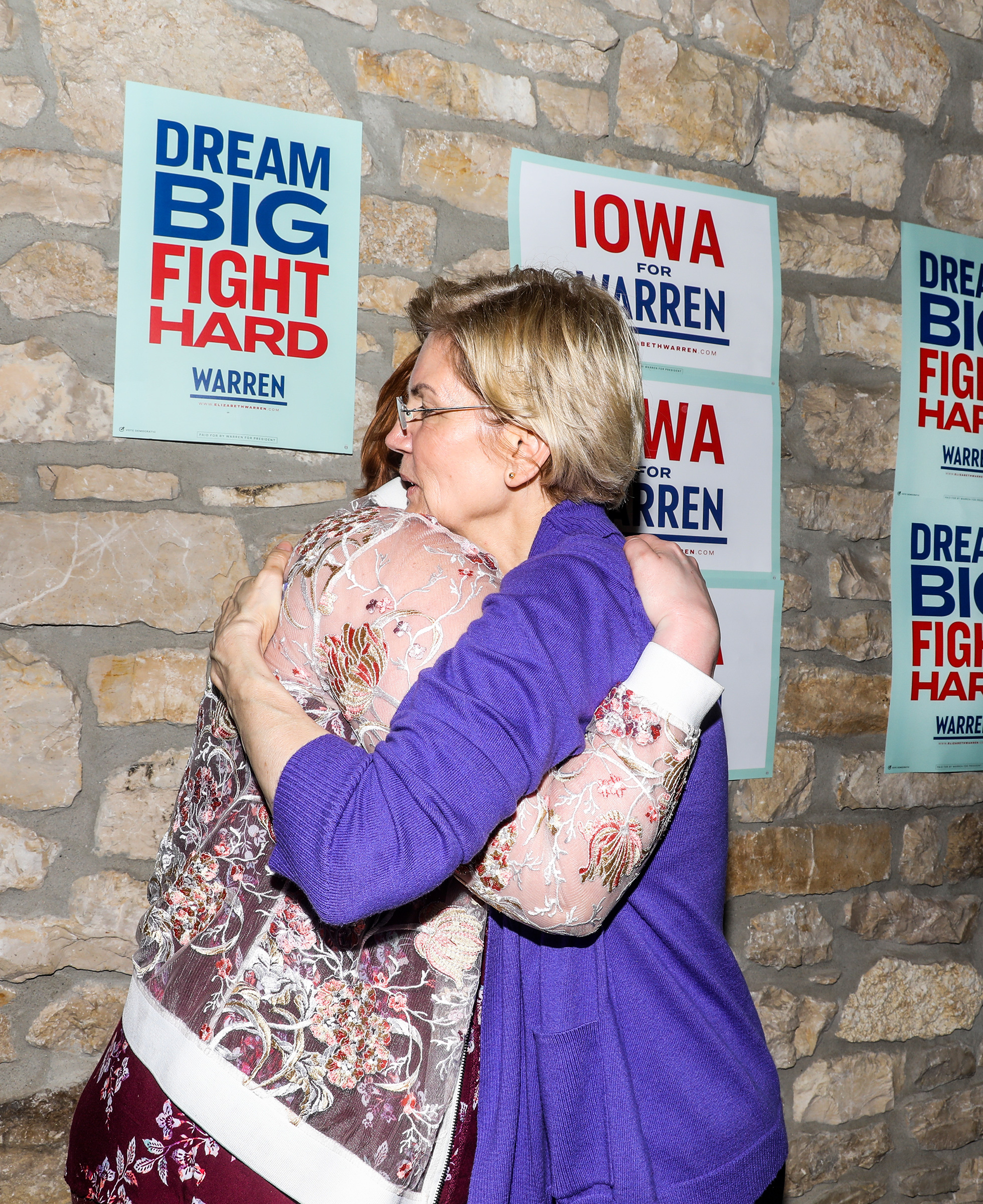

Warren’s policy proposals have become her brand. On the campaign trail, her off-the-cuff phrase “I have a plan for that!” became so ubiquitous that it morphed into a viral applause line; in Iowa, supporters printed the accidental slogan on T-shirts. Her campaign, staffers say, is built on the conviction that voters want substance, not theatrics, and will throw in for the candidate who puts forth serious ideas to create change.

It’s an audacious bet in the Donald Trump era. Voters tend to tell pollsters they prioritize policy over personality. But they said that in 2016 too, when Clinton’s detailed agenda was no match for Trump’s simple slogans and schoolyard nicknames. As her Democratic competitors offer enticing promises largely devoid of specifics, Warren insists on talking nuts and bolts. In her stump speech, she describes the mechanics of a tax that would fund her universal child-care plan, to pick just one example among many.

Warren’s investment in substance over style is not her only gamble. Over the past few months, she has fired her finance director, eschewed high-dollar donors and hired as much as 10 times as many staffers in early voting states as most of her competitors. While others focus on big money and flashy rallies, she’s building a campaign designed to maximize the amount of time she spends in living rooms and community centers talking about what she would do as President.

It’s not clear whether these bets will pay off. What she’s proposing is a return to a bygone economic model that hasn’t existed for at least a generation—a tough sell among even staunch members of her own party. And while she has emerged as a serious contender for the Democratic nomination, she still trails front runner Joe Biden by a wide margin in both national polls and the latest surveys of the first four primary states. She doesn’t have the die-hard fan base that Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders built in 2016, and her campaign may be haunted by the specter of Clinton’s failure. Many voters who like Warren worry about nominating a wonky, blond woman four years after another wonky blond woman lost to Trump. “People are saying, if it takes a white dude to get this guy out of office, so be it,” says Kelly Whitman, a Pennsylvania voter who heard Warren speak in New Hampshire.

But the first votes in the 2020 primaries will not be cast for nine months. In the meantime, Warren, 69, is committed to running what she describes as “a different kind of campaign”—offering a more unapologetically liberal agenda than any presidential candidate in recent memory. “I want to fix the systems in this country so they work for Americans, not just for giant corporations or Big Pharma or the Goldman Sachs guys,” she says. “That’s not just my political career. That’s my whole life’s work.”

I first met Warren in mid-April, in the basement of a New Hampshire hotel. She and her family had just wolfed down a lunch of Mexican takeout; a side table was littered with guacamole containers, and her golden retriever, Bailey, sat nearby, panting amiably. I asked if she thought she could win that elusive demographic: white, working-class voters who supported Barack Obama in 2008 and President Trump in 2016. She didn’t miss a beat. “Those are my people,” she said, and then repeated it, sitting stick-straight in her chair. “Those are my people.”

Warren, née Elizabeth Herring, was born in 1949 into a lower-middle-class family in Oklahoma City. All three of her brothers were in the military; two are Republicans. Warren herself was a registered Republican until the mid-1990s, although she says she was not very political at that time. Her family’s financial struggles mirrored those of many alienated voters in middle-class America today—a visceral experience that she says has defined and informed her politics.

When she was a child, Warren’s father sold everything from carpeting to fencing and housewares. In the early 1960s, he suffered a heart attack and could no longer work, plunging the family into crisis. Warren recalls learning the word foreclosure by listening to her parents’ hushed conversations after bedtime. In an effort to keep the family home, Warren’s mother got a minimum-wage job at a nearby Sears. Warren remembers her walking to work in the same nice dress she wore to weddings and graduations.

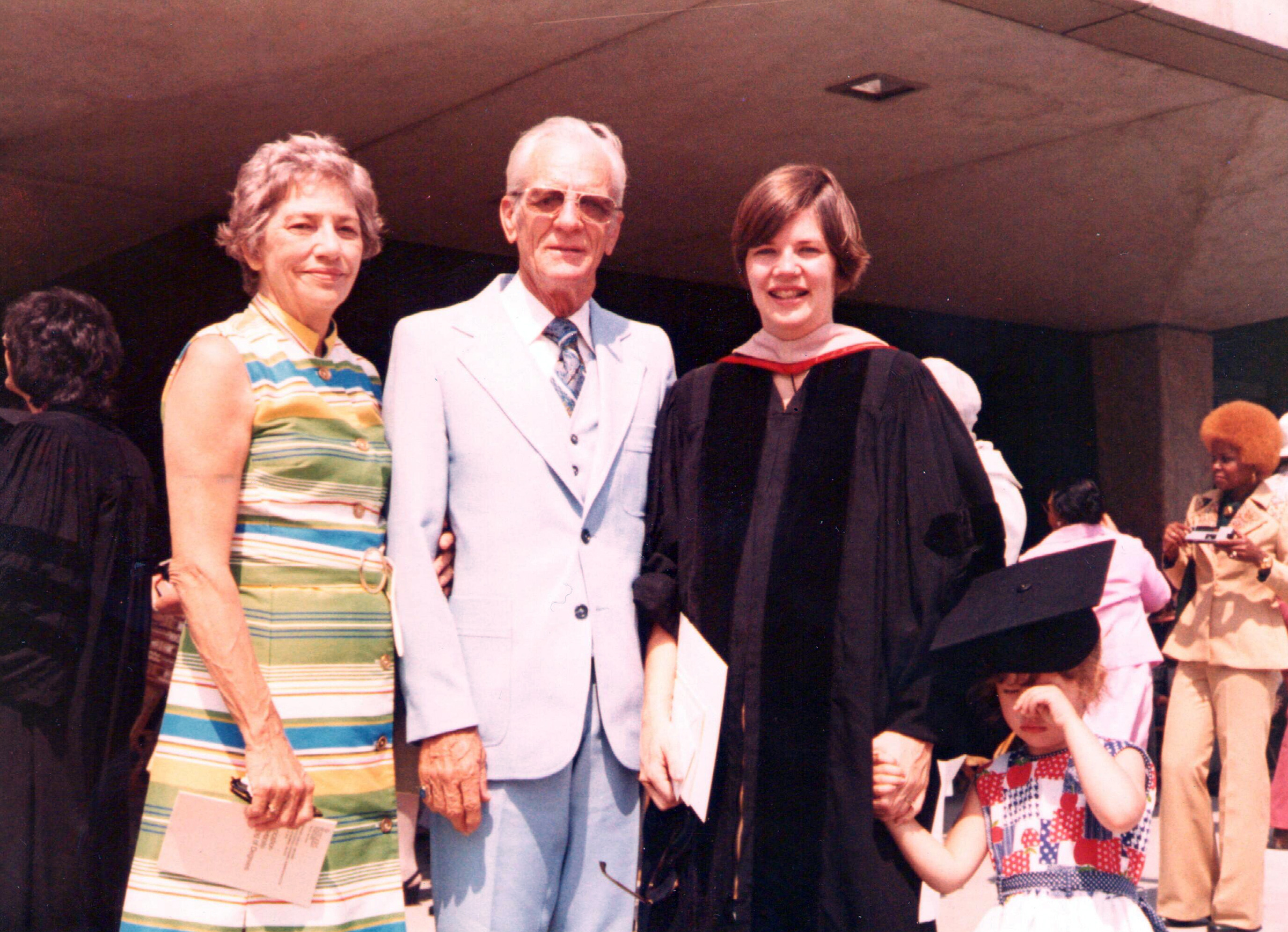

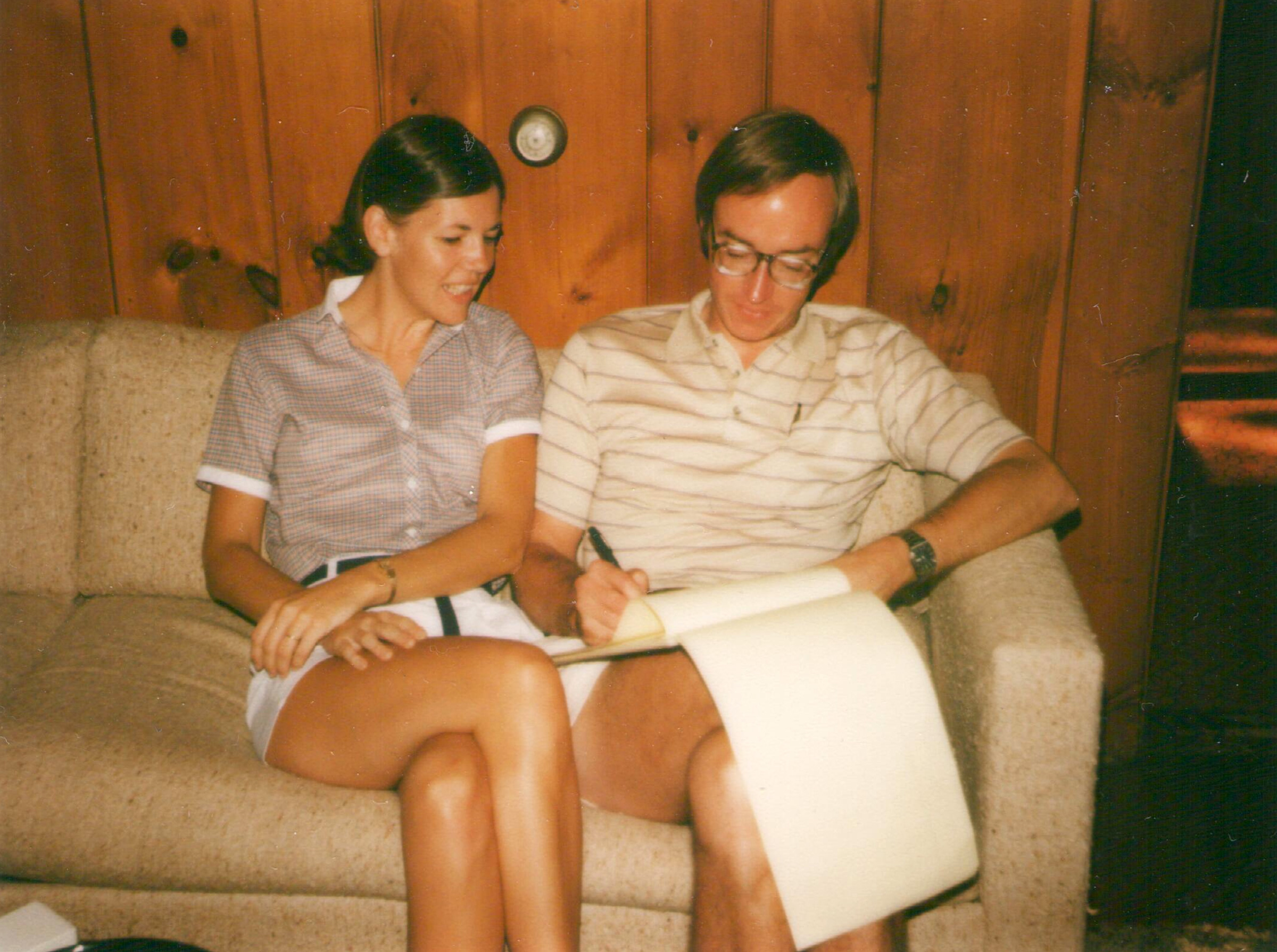

Warren also remembers her own rocky path through young adulthood. When she was 19, she dropped out of George Washington University, where she had earned a debate scholarship, when she was still a teenager, to marry her first husband, Jim Warren, with whom she had her two children. During those early years, Warren recalls struggling to balance her own ambitions to finish college and go to law school with being a young wife and mother. She juggled classes and child care while following her husband’s career as a NASA engineer, which took them zigzagging from Texas to New Jersey and back again. She remembers getting offered her first job, as a special-needs teacher in New Jersey, while frying pork chops for dinner “and trying not to trip over crayons.” Later, just days before she was set to begin classes at Rutgers Law School in Newark, N.J., she recalls potty-training her not-yet-2-year-old daughter “in a panic” because the only day care she could find would not accept kids in diapers. “I’m here today thanks to three bags of M&Ms and a compliant toddler,” she told a New Hampshire audience, to appreciative chuckles.

After graduating and passing the bar, Warren again followed her husband’s career back to Texas, where she became a professor at the University of Houston Law Center. (She later divorced Warren and met her current husband, Bruce Mann, a fellow Harvard professor, to whom she has been married for almost 39 years.) It was during this period that she started her academic research into why American families file bankruptcy. She began the study expecting to discover that those reneging on their debts had made bad choices or had moral failings, she says. Instead, she found that they were “like you and me or our neighbors. They got into trouble because of a medical emergency or a string of bad luck.”

By her own telling, Warren’s personal story is littered with similar close calls and almost failures, which she survived thanks to a supportive family and good government. “I came within a hair’s breadth of getting completely knocked off the track,” she says. The reason her parents were able to keep their home when she was a girl is that at the time, a minimum-wage retail job paid enough to cover the mortgage, she says. The reason she was able to keep her job as a law professor in Houston is that her aunt offered to watch her kids. A minimum-wage job today “can’t keep a mama and a baby out of poverty, and that’s wrong,” she says. She’s proposing universal child care and pre-K for every working parent, she says, because “not everyone has an Aunt Bee.” How many smart women were unable to pursue careers because they couldn’t secure child care? she asks. How many hardworking people didn’t advance because they couldn’t afford the loans to cover their educations? “No one,” she says, “makes it alone.”

Warren remains close to her family, most of whom still live in Oklahoma, and a Plains accent still inflects her speech. But her personal story also makes for useful politics. As a veteran Democratic strategist observes, “If she’s Oklahoma Elizabeth Warren, she’ll win. If she’s Harvard Elizabeth Warren, she’ll lose.”

The Oklahoma Warren is not an act, says Heather Campion, an executive and women’s leadership consultant long involved in Massachusetts and national politics, who has known Warren since the mid-2000s. “Truly, at heart, she’s a working-class person,” Campion says. “She’s not a Harvard professor, either culturally or socially, and because of that, she understands very deeply what it’s like to be a working American today. She has had her finger on the pulse of what’s happening in this country long before anyone else did.”

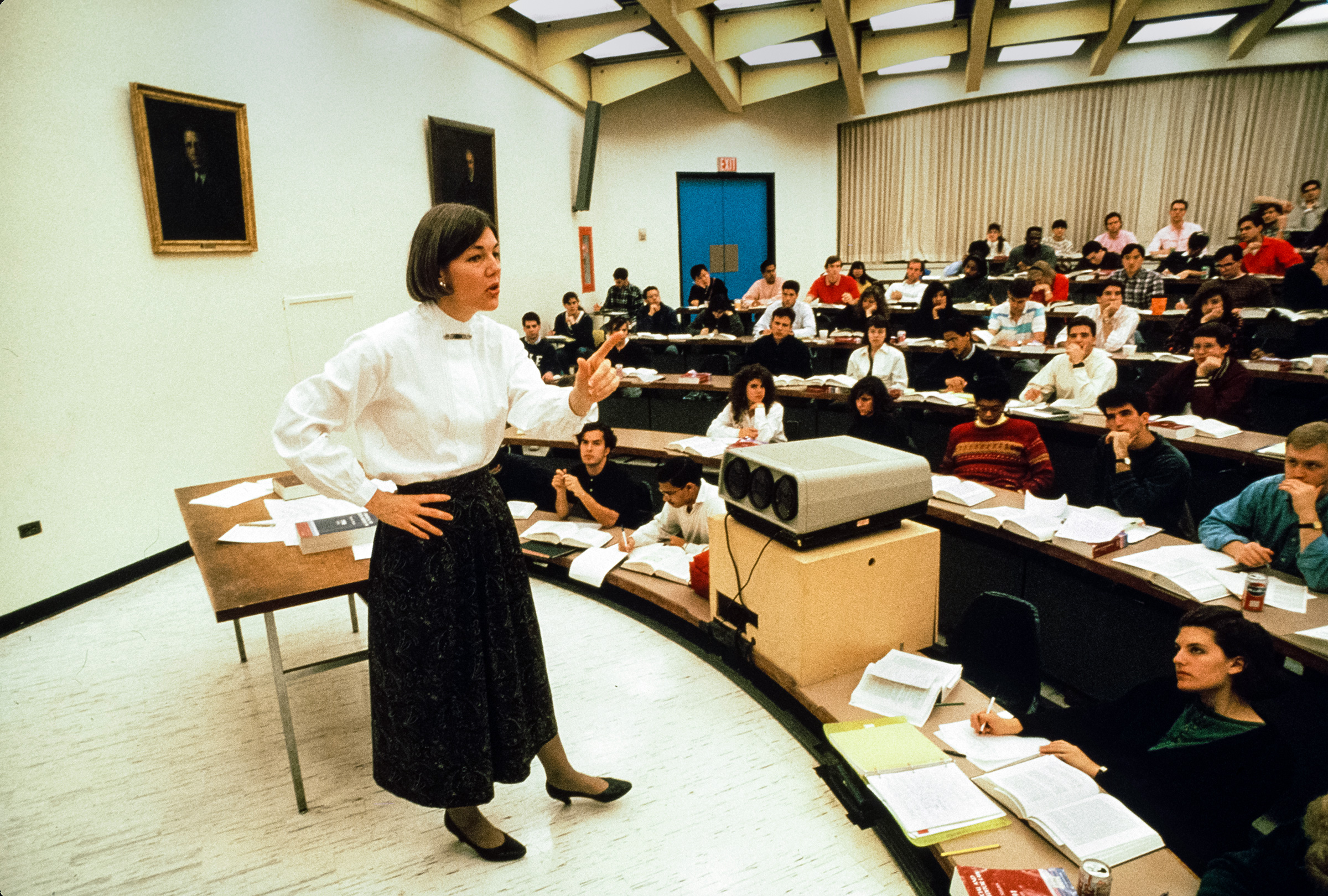

But Warren’s political rivals have often succeeded at weaponizing her Harvard side. In her first campaign for U.S. Senate in 2012, her opponent, Republican incumbent Scott Brown, called her “the professor” and lambasted her “elitist attitude.” Trump has nicknamed Warren Pocahontas, in a nod to her decision to identify herself as a Native American while she was a law professor, including at Harvard. Critics have alleged that her claim to minority status was an attempt to boost her career. (Warren has apologized for the claim, and an investigation by the Boston Globe found she did not benefit from it professionally.)

Warren’s first foray into Washington politics didn’t come until the late 1990s, when she came to D.C. to fight a bankruptcy bill she believed unfairly penalized families by making it more difficult to discharge credit-card and medical debts. As part of her effort to quash the legislation, she lobbied then First Lady Hillary Clinton, who ate a hamburger as Warren made her case. By the time the brief conversation was over, Clinton was sold: she persuaded her husband to pull support for the bill, and it died. It was Warren’s first political victory—but a short-lived one. In 2005, the same piece of legislation again came up for a vote, and that time it passed.

The defeat marked the first time Warren locked horns with Biden, then a Delaware Senator and now a top rival for the Democratic nomination. During a February 2005 hearing, the two went toe to toe: Biden, whose state hosts some of the biggest financial firms, took the credit-card companies’ side, while Warren advocated on behalf of the families who she said had “been squeezed enough” by interest rates and fees. Biden was not swayed but ended the debate by acknowledging Warren’s skills. “You are very good, professor,” he said, according to a transcript. Biden voted for the bill both times.

The failure to stop the bankruptcy bill still rankles Warren. But it also helped shape her understanding of how Washington works, says Dennis Kelleher, president and CEO of Better Markets, a nonprofit financial-reform group. “People have no idea what it means to go up against the overwhelmingly powerful and connected financial industry, which will do almost everything to protect its businesses and profits,” he says. Warren’s battle scars from her own fight made her “tougher and smarter” and taught her to “take fight to the public,” he says. It was a lesson Warren would use again soon.

Warren saw the financial crisis coming before almost anyone else. Throughout the early 2000s, she warned in articles, books and speeches that rising consumer debt, wage stagnation and spikes in the cost of housing, health care and education would pull the rug out from underneath the American economy. In September 2008, it finally happened: the financial markets crashed, plunging the world into the worst recession in a generation.

Weeks later, former Senate majority leader Harry Reid appointed Warren to chair the five-member congressional oversight panel charged with reporting on the effectiveness and transparency of the U.S. Treasury’s Troubled Asset Relief Program, the centerpiece of the federal government’s response to the crisis. In that role, Warren quickly won acclaim for grilling senior officials of both parties.

When then Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson repeatedly evaded the panel’s scrutiny, Warren and her team created a chart listing every time he had been asked the same question and how he had answered it previously. Warren was no easier on Paulson’s Democratic successor, Tim Geithner. In one cringe-inducing moment, Warren asked Geithner why auto companies’ creditors were asked to take huge losses during the crisis while taxpayers paid financial institutions’ creditors in full. Geithner, fiddling with a pen, wobbled through a response before admitting that the Treasury was “forced to do things we would not ever want to do.” Within months, Warren’s interrogations became viral fodder for a furious public, transforming the obscure law professor into something of a populist folk hero, as well as a regular on Jon Stewart’s Daily Show.

During the same period, Warren began working with former Democratic Congressman Barney Frank and former Democratic Senator Chris Dodd on what would become their signature legislation, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Warren’s reputation as a bomb thrower preceded her, but Frank was impressed. “When we actually got into legislative drafting, she was unusually good for someone who wasn’t involved with the political process,” he says. Warren was committed to “tactical flexibility,” Frank added, “ordering your priorities, fighting for the ones you think are most important” and being willing to compromise on the rest.

It’s a characteristic that critics and fans alike often miss. Warren has introduced more substantial bipartisan legislation during her time in Congress than nearly all her rivals in the Democratic primary field, according to the nonpartisan website GovTrack, including Sanders, New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, California Senator Kamala Harris and New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, who has touted his propensity for reaching across the aisle on the campaign trail. (Only Biden and Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar have introduced more.) Most recently, Warren collaborated with Republican Cory Gardner of Colorado on legislation pushing for state control of marijuana laws and with Republican Bill Cassidy of Louisiana on an effort to make colleges’ graduation and employment data more transparent.

Her singular achievement in the wake of the financial crisis was persuading Congress to create a new watchdog agency, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), as part of the Dodd-Frank law. The goal of the CFPB was to protect and advocate for consumers against sloppy, abusive or predatory financial firms. From the start, Warren’s agency was controversial, in part because corporations staunchly opposed it. After its creation in 2010, the CFPB became one of the most feared watchdogs in Washington, forcing financial firms to pay back billions of dollars to consumers. In 2013, Ocwen Financial Corp. paid a $2 billion penalty to underwater homeowners for engaging in what the agency called “deceptions and shortcuts in mortgage servicing.” In 2018, Wells Fargo paid $1 billion to borrowers with home and auto loans.

A 2017 poll by consumer-advocacy firms found that three-fourths of Americans, including 66% of Republicans and 77% of independents, supported the CFPB. Yet since 2017, the Trump Administration has worked to defang the agency. Its former acting director, acting White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney, who previously co-sponsored legislation to abolish the CFPB, ordered a hiring freeze, slow-rolled enforcement measures and stood in the way of new rules that would have restricted payday loans.

At a campaign stop in Hanover, Warren takes the stage at a near run as Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down” booms in the background. If you were to watch a video of Warren on the trail with the sound off, you might be forgiven for thinking she was conducting a high-tempo aerobics video: when she speaks, she rocks and bounces onto her tiptoes and pounds the air with her fists, her tone veering between outrage and empathy as she describes the challenges facing the middle class. Just as her diagnosis of the problem reaches a crescendo, she takes a step back and performs a rhetorical swan dive into crystalline pools of policy: and here, she says, is how we fix it.

It’s a two-step presentation that can sometimes feel like therapy to supporters. “They’re happy that somebody is finally talking about it,” Warren says. In the Washington Bubble, as she calls it, the conversation is tone-deaf. Investments are up, unemployment is down, and pundits are arguing over whether the good times are thanks to Obama or Trump. And while it’s true that traditional measures of economic health, like GDP and stock prices, are indeed on the rise, many Americans inhabit a different reality: overworked, underwater and feeling crushed by powers outside of their control. “She knows me. She knows my life conditions,” says Greta Shultz, a single mom from Massachusetts. “I don’t care if Beto’s jumping on counters or Biden’s the front runner. She’s the policy machine who can fix it.”

Warren’s solution involves taking on some of the biggest, most powerful political and economic institutions in the country: ending unlimited corporate campaign spending, rebooting antitrust laws, breaking up big tech and agricultural firms, and reforming lobbying. She describes a wall of interlocking gears, each connected to the others, forming the American economic and governmental machine. Beginning sometime around 1980, she says, those gears stopped fitting together and the machine stopped working for most Americans. “If we want to make real change in this country,” she says, “it’s got to be systemic change.”

The foundation for Warren’s social-policy programs are two new taxes, a corporate tax and what she calls an “ultra-millionaire” tax. The first is a 7% tax on businesses’ profits that exceed $100 million in a year. The second is a 2% tax on household wealth that exceeds $50 million annually. (The tax increases to 3% on anything over $1 billion.) It would affect roughly the top one-tenth of the richest 1% of Americans. “You built a great business? You earned or inherited a lot of money? Great, keep most of it!” she says. “But by golly, pitch something back in.” Warren estimates that, together, these taxes would raise $3.75 trillion over a decade—funds she would use to pay for many of her big social programs.

Some Republicans have been critical of Warren’s tax plan, and some tax experts have said it would be both difficult to implement and likely unconstitutional. Progressives too have been critical of some of the details of Warren’s proposals. Kevin Carey, director of New America’s education-policy program, argues that while Warren’s goal of providing free college is a good one, her plan is designed in a way that punishes states that currently do more to support students. Warren’s affordable-housing plan has also come under scrutiny for its reliance on incentivizing local governments to remove zoning restrictions.

Warren’s deeply liberal policies reflect a larger political bet: that her vision for the future will endear her to a nation—and a Democratic Party—in the throes of a populist resurgence. Trump won in 2016 partly by harnessing anti–Wall Street language. His campaign featured ads lambasting then Goldman Sachs chief executive Lloyd Blankfein and pillorying Clinton as a stooge of Wall Street. Warren’s campaign wants to appeal to that sentiment.

What Warren’s many plans conspicuously lack is a detailed description of how she will change the politics that have stymied other populist efforts in the past. For starters, her own party has for decades embraced a neoliberalism that mostly shies away from big government programs. “It’s so clear now that that approach hasn’t worked. We’ve got to find a different path,” Warren says.

And then there’s Republicans. Passing any of Warren’s proposals would require more than just winning the presidency—a fact she acknowledges. “Yes, I want to win in 2020, but that’s not enough,” she told a crowd in Lebanon, N.H. “We have to, as Democrats, take back Congress, we’ve got to boost our seats in statehouses, we’ve got to take some governors’ mansions back.” Not since Lyndon Johnson and Franklin Roosevelt enjoyed stable Senate supermajorities, and a sympathetic Supreme Court, has such sweeping transformation been possible. For now, Warren’s answer is to double down on change—she has called for Trump’s impeachment—while appealing to brute optimism. “They say, ‘Impossible,’” she says. “I hear, ‘Try harder.’”

Her first step will be to convince voters that she can beat Trump. An April CNN poll found that 92% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents said a candidate’s chances of beating Trump were “extremely” or “very important.” Biden’s perch atop the Democratic field may be in large part a function of that conviction. An April Quinnipiac poll found that 56% of Democrats believed Biden was the candidate most likely to oust Trump; Sanders came in second, with 12%.

Some of the skepticism about Warren’s prospects arises from her own mistakes. Her decision in October to release her DNA analysis, which indicated she likely has a distant Native American relative, was widely panned. The move was an attempt to get ahead of a bad story; Boston shock jock Howie Carr announced in March 2018 that he had previously tried to get a DNA sample from Warren’s spit on a pen and encouraged his Boston Herald readers to snatch her water glass at a St. Patrick’s Day event so that he could test it. But Warren’s willingness to engage with that narrative, taking Trump’s bait in the process, came off as ham-handed. “The whole Native American thing was stupid,” says Massachusetts voter Cindy Walker. “She’s capable and competent to do the job, but she’s got these negatives.”

Warren has also tangled with powerful members of her own party. In early 2018, she attacked fellow Democrats, including several facing tight re-election campaigns, for backing legislation watering down Dodd-Frank. “That was a mistake,” Frank says. “I think she realized she misplayed that.” Warren also faces challenges beyond her control, including how some men react to outspoken women.

But campaign aides say they’re playing a long game. While Biden and Sanders may be better known, Democratic strategists unaffiliated with 2020 campaigns say Warren has proven appeal. In 2012, the Obama-Biden re-election campaign found that of all the Democratic campaign surrogates, Warren resonated most powerfully in focus groups. “The sense was that she gets it, she understands us, she is fighting for the right stuff,” says a former senior aide to the Obama-Biden re-election campaign. “She had an authority that no one else had.”

For now, Warren swats away questions about perceptions, polling numbers or electability. “I didn’t look in the mirror as a kid and think, Hey, there’s the next President of the United States,” she says. “But I know why I’m here. I have ideas for how we bring systemic change to this country. And we’re running out of time.”

Correction, May 10:

The original version of this story misstated the state where Elizabeth Warren first worked as a special needs teacher. It was New Jersey, not Texas.

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision