Whenever I fly on an airplane, I always try to get a window seat. My favorite moments are takeoff and landing, when I’m down below 500 feet, so low that I can see the world in three dimensions. I used to own that airspace. Or at least I felt like I did, from the seat of my flying lawn chair.

I fly motorized paragliders, a kind of ultralight aircraft that uses a backpack motor and a parachute-style wing, with my body serving as the fuselage. They are often flown by fun-hogs and thrill-seekers, but I’m not some adventure dude. I’m a photographer who flies, and I only fly for pictures. I have specialized in aerial photography for the past two decades, shooting books and magazine assignments for National Geographic, The New York Times Magazine, GEO, and The New Yorker. I spent fifteen of those years working on a book about the world’s extreme deserts, flying with my camera in every hyper-arid region of the world, the remotest parts of 27 different countries. My strong legs and a dose of determination were the keys to my sweet spot in the sky.

During all this time, I felt like I had a lock on the “low and slow” perspective below 500 feet. But that monopoly has abruptly disappeared with the rise of drones. Nowadays I can get almost the same photographs with a drone that I can with my paraglider, without any risk at all. A takeoff now is routine thumb-play for amateurs; my teenage sons use their drone to find lost baseballs on our roof.

TIME Special Report: The Drone Era

I too have come to embrace the new technology. As a pragmatic photographer, drones offer unparalleled precision in the sky. I can hover to get the exact angle and aerial perspective I want, anywhere from ladder height to 400 feet up. As an aerial specialist, I’m excited by the visual possibilities that drones have made available. I have a small squadron of quadcopters, each with different sizes and capabilities.

But in spite of all the hype, drones have not entirely replaced the usefulness of airplanes, helicopters, or, in my case, motorized paragliders. They are only the shiniest new tool in the drawer. And the new tool has limitations: In the U.S., they can’t legally be flown over 400 ft. or out of the pilot’s line of sight, and their batteries are typically only good for about twenty minutes of flight time. You’re also limited to seeing only what the drone’s camera is feeding to your smartphone, so I sometimes feel like I’m flying a video periscope. It makes it easy to back up into a tree.

For serious aerial photography, there are now three options: If you know your subject and can get within range, drones are pretty darn terrific. If you want to cover a lot of territory and look around, take a plane or helicopter with a local pilot who knows the area. And if you want to go out exploring really remote areas, like the middle of the Sahara Desert, well, I still have a monopoly there with my motorized paraglider.

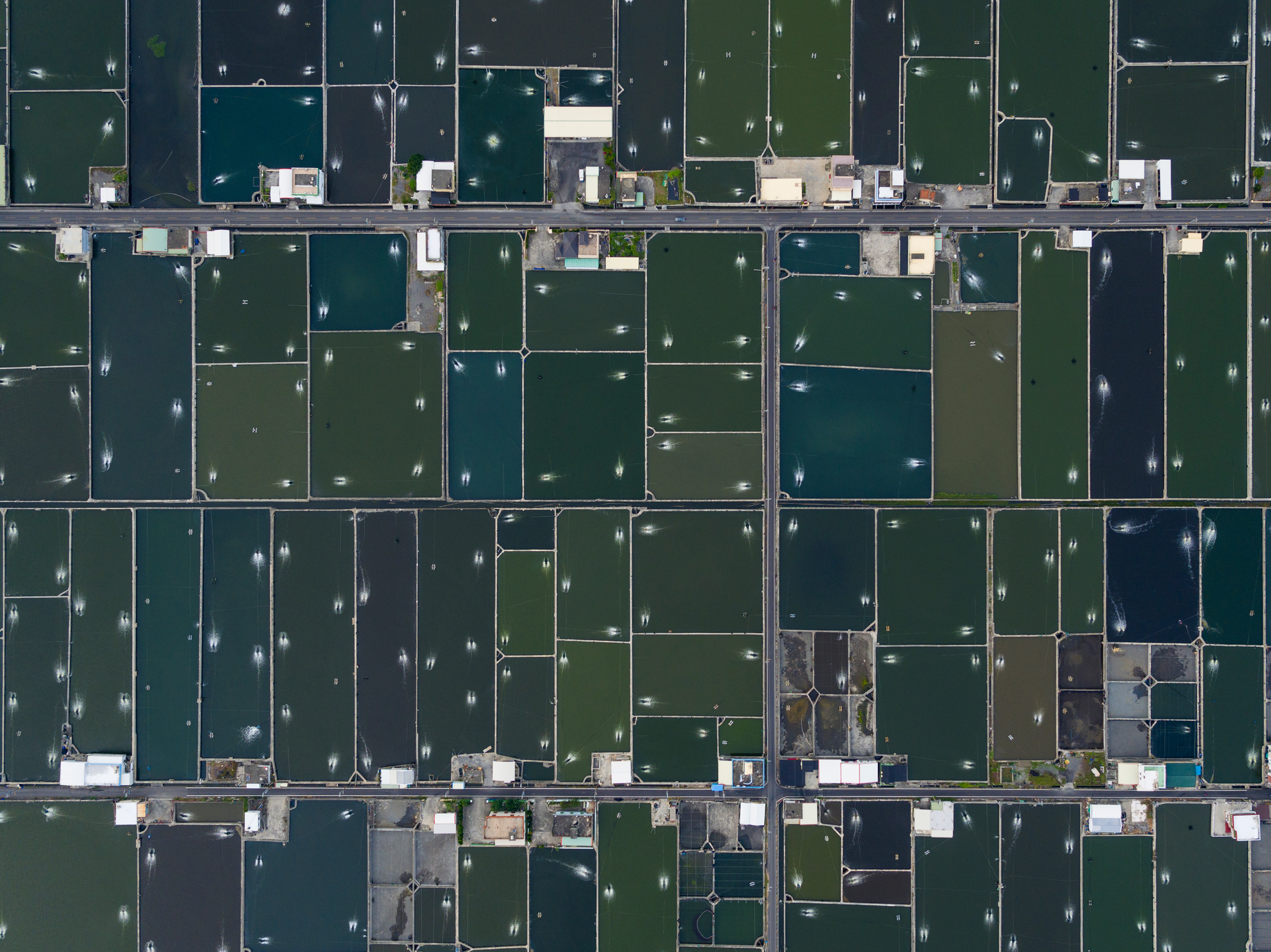

In many ways, drones have done to aerial photography what smartphones did to cameras. Their cost and ease of use have made it so that everybody can take an aerial photo or video. But that’s not to say everyone can take a good aerial picture. A monkey can take a photo with an iPhone, but I have yet to see one fly a drone — although it would be (expensive) fun to try. To me, there is a visual language to seeing in the sky. And just as smartphones have dumbed down photography with the loss of depth of focus, shutter controls, and choice of lens, most drones have dumbed down aerial photography, too. People have come to accept the look of cheap drones with super-wide perspectives, poor optics, and, more often than not, the user’s choice of a straight-down view. It’s as if all there is to Chinese food is sweet-and-sour pork.

A crayfish festival in Xuyi, China. Photographed by drone.

Sometimes I do miss the physical sensation of actually being up there. A drone flight can feel like a video call instead of being face-to-face with our most amazing little planet. But I’m also excited about the new visual situations and perspectives that drones have opened up for me. Over the past few years, I’ve been able to fly my drones from the deck of a sailboat in Antarctica, inside a big computer factory in China, and even had one cozy up to a nervous herd of zebras at a watering hole in Botswana. For me, photography has always been about showing people something that they have never seen before. Drones have done that in spades by opening up a whole spectrum of exciting possibilities, and they have done it for almost everyone. What we are witnessing is nothing less than the grand democratization of aerial photography. For better or worse, there is simply no turning back.

George Steinmetz is an aerial photographer based in New Jersey. Follow him on Instagram @geosteinmetz.

Josh Raab is a TIME Multimedia Editor. Follow him on Instagram @instagraabit.

Erin O’Flynn is a Photo Intern at TIME. Follow her on Instagram @erin_oflynn.

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision