After photographer Alyona Kochetkova was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer in July 2017, she decided to turn the camera on herself and document her treatment. She completed medical treatment in March 2018.

I was diagnosed with breast cancer on my 29th birthday. When the doctor told me, I was shocked. I could not understand how a person with a healthy lifestyle — which I thought I had — could get cancer. Cancer is the second most common cause of death globally, and 1 in 8 women in the U.S. and EU will develop breast cancer in her life. Still, I didn’t know anything about it and couldn’t imagine how to move forward.

Being a photographer for more than 10 years, I was used to making stories that reflect things happening outside me. When I was diagnosed with cancer, it was time to make myself the subject. I didn’t want just to document all the stages or make a frightening story. My goal was to create visually striking images that would help break the stigma around the diagnosis and allow people to better understand what a person facing serious disease feels like. I hope that my story will inspire other cancer patients to find their way through such a difficult period in their lives.

At first, I feared for my life and was too worn out to take photos, but my treatment plan gave me hope for recovery, one of many emotions I would feel as I sought to rid my body of this disease. There were moments of depression, moments of bold confidence that everything would be all right, moments of tiredness that seemed endless and moments of morbid introspection. The illness made me reassess my entire life. I tried to capture it all.

I was just making the photos for myself at the beginning, but when I met other cancer patients in the hospital — and especially after I showed some of the images to a patient who had become a close friend — I understood that many of them had similar thoughts and fears. Since then, some of the other patients have also become my good friends. I think that one of the most significant points of photography is that it speaks about things that are hard to express with words. It is a universal language that people all around the world can understand.

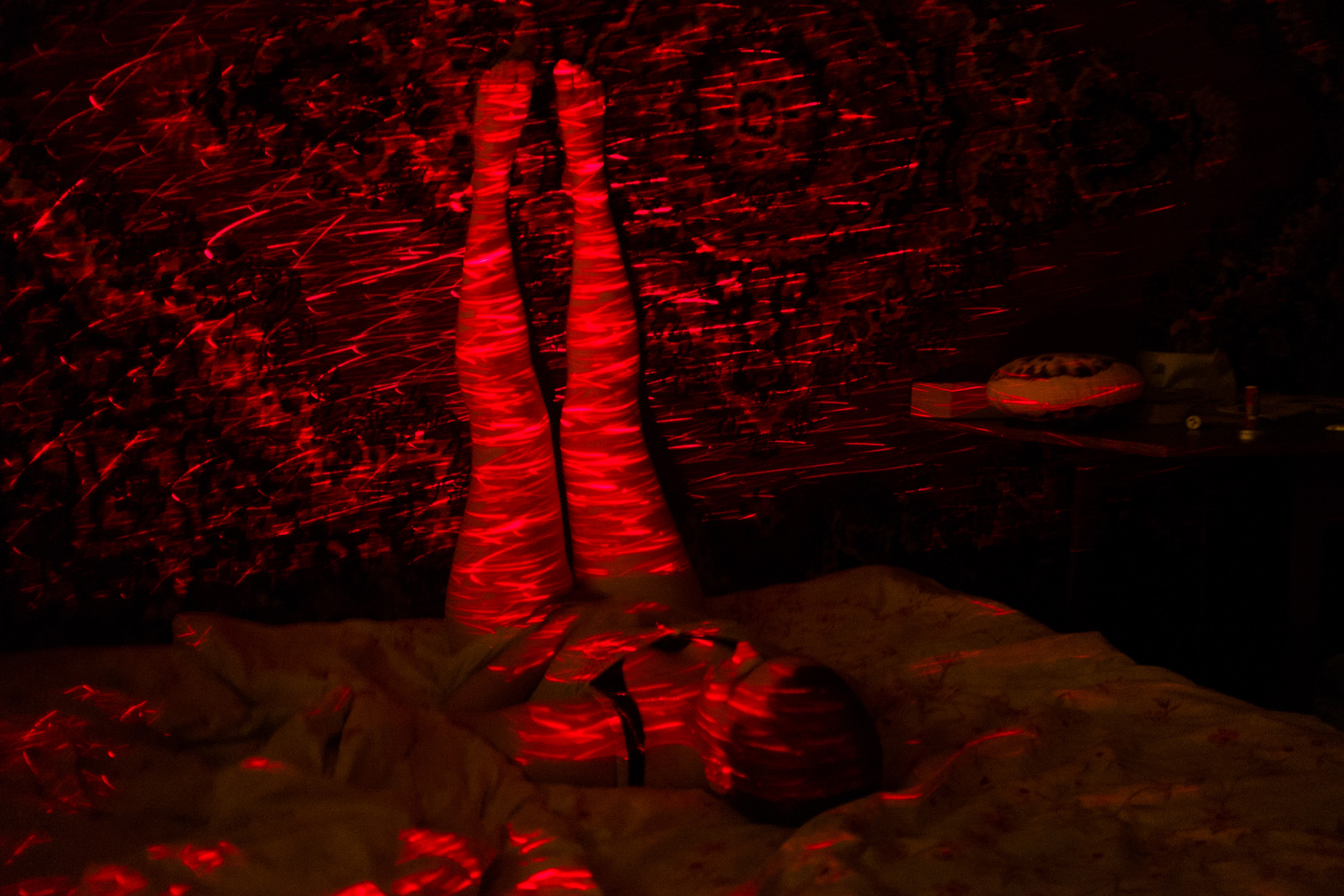

During chemotherapy, my immune system was weakened. I was making self-portraits lying on my bed during nausea attacks. I started to experiment with my red night lamp and its color perfectly matched my feelings, an interesting coincidence considering one of the main prescribed chemotherapy drugs was also red.

I was unable to travel and shoot outside as before. Sometimes I even couldn’t go out. I felt like a prisoner in my own house. Photography became my only activity and the link to my life before the disease. It also became a form of art therapy, which was important when, feeling ill and staring at my swollen face and newly bald head, I felt like isolating myself.

All my life, I’d had long hair. During chemo, it started to fall out so I cut off my plait — a painless but emotional loss. This image became one of the most memorable of my project, a symbol of the physical and mental changes I had to accept.

During this time, I also experienced chemo brain fog, a common term used by cancer patients and survivors to describe thinking and memory problems that can occur during and after cancer treatment. I was not able to concentrate on anything. I sometimes felt like shattered glass.

But it’s not easy to show the sensations, which are totally internal and not visible to observers. After the first chemotherapy course, I started to feel strong pain in my bones, like glowing embers. It flared in different parts of the body, and it was hard to find a comfortable position. I bought a laser pointer and started to experiment.

I tried to keep up my strength and I understood the importance of eating, but I had no appetite. I typically like borsch, a nutritious and invigorating beet and beef soup that’s popular in Russia, but after chemotherapy, food becomes disgusting. Such a simple thing became a serious problem because of strong nausea and taste deviations, so I kept delaying the meal-making photos.

Some cancer survivors would like to forget the period when they were ill. I don’t feel like that. Life is complex: there is pain, disease and death and there is joy, hope, faith and love. During my treatment, my sister got married. I bought a bright red wig, put on one of my favorite dresses and went to the wedding party. It was not easy, but it was fun and I felt that I was still living my life.

Like so many people, I wondered, Why did it happen to me? There’s no real answer, but being a person of faith I understand that disease can be a test, not a punishment. It reminds you to think about your priorities – do something useful, create something, help others instead of just consuming. And it is a part of life, which teaches us and leads to spiritual transformations. A lot of things that I had considered important turned out to be insignificant and faded. Now I try to be kinder to people around me and to spend more time with my relatives.

I know my family and friends were stressed during my treatment too, but they always showed me love, gave me hope and made me stronger. As difficult as it can be, it’s not the time to quarrel. Even the most advanced treatment does not guarantee remission.

My goal here isn’t to scare people who haven’t dealt with cancer in their lives. What I want to show is that my story isn’t a singular one. It’s similar to stories of plenty of people suffering from cancer all around the world. Not all of them can speak about it, but all of them need love and support.

Alyona Kochetkova is a Russian freelance photographer and photography teacher.

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time