When photographer Elliot Ross and I traveled the 2,000 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border it was the spring of 2017. The post-election climate had enflamed a sense of cultural and political difference in the United States — much of which centered around the debate about the border wall. We set out expecting to find residents there who were fundamentally vexed by the relationship between the United States and Mexico; between immigrant, indigenous and Caucasian communities; and between border inhabitants and undocumented migrants. Instead, we found the opposite — and heard about fears largely left unvoiced.

While the issue of President Trump’s wall was seeding deep divisions within the greater population, it was building consensus and accord in border towns and cities — across demographic, racial and partisan lines. “It has brought a lot of people together,” explained Louis Harveson, a professor at Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Tex.

The adjacent counties of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California are peaceful, tight-knit communities that more often than not voted Democratic in the 2016 presidential elections. But they are also bonded by a crisis of faith. Much of this concern stems from the 649 miles of physical barriers built for the Department of Homeland Security under George W. Bush’s 2006 Secure Fences Act, which required the construction of a set minimum of fencing. The U.S. Border Patrol first began erecting physical barriers on the southern border in 1990 with a 14-mile-long primary fence separating Imperial Beach, Calif., from Tijuana, Mexico. Further construction stalled due to environmental concerns until the Secure Fence Act mandated that the Department of Homeland Security complete no fewer than 700 miles of fencing.

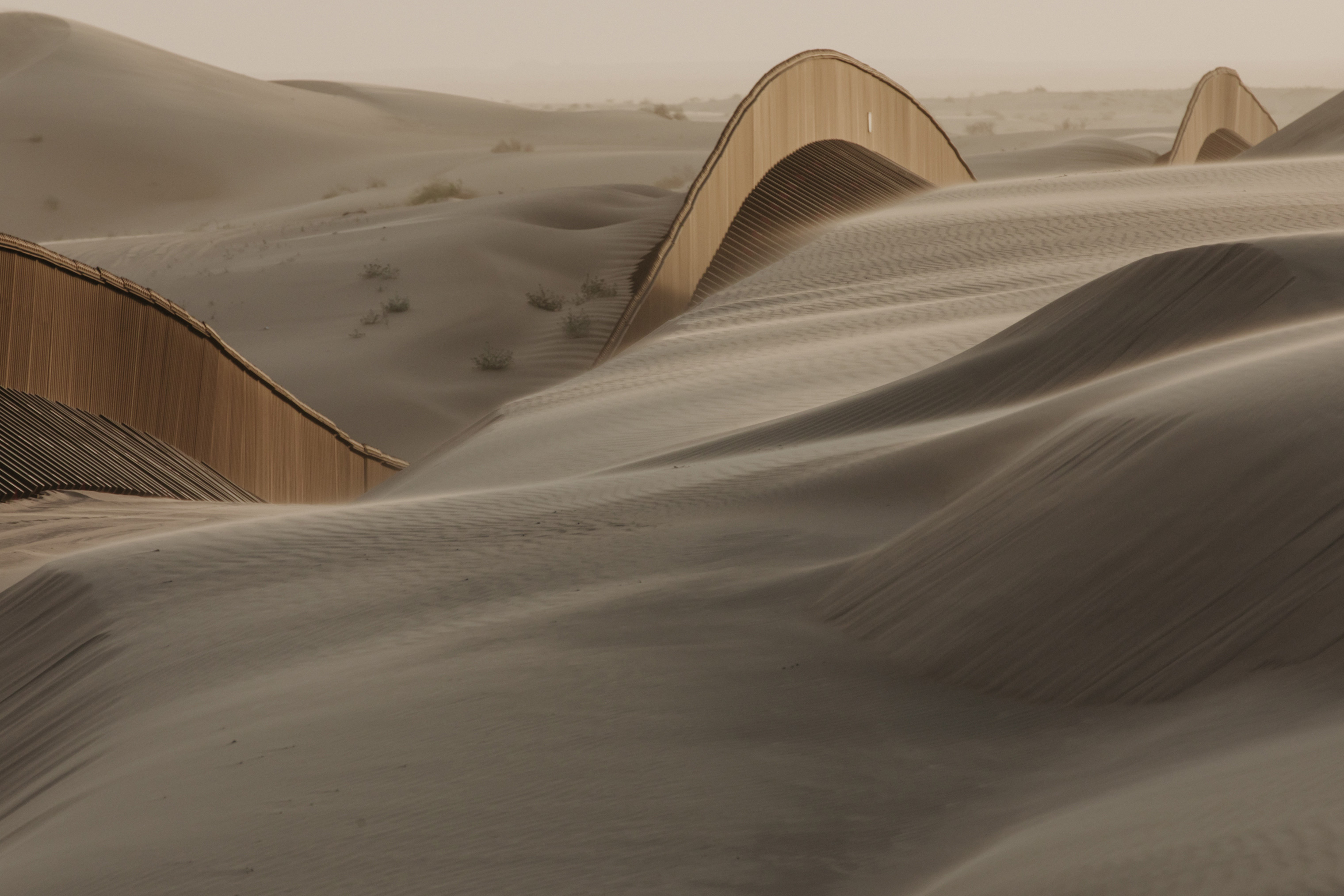

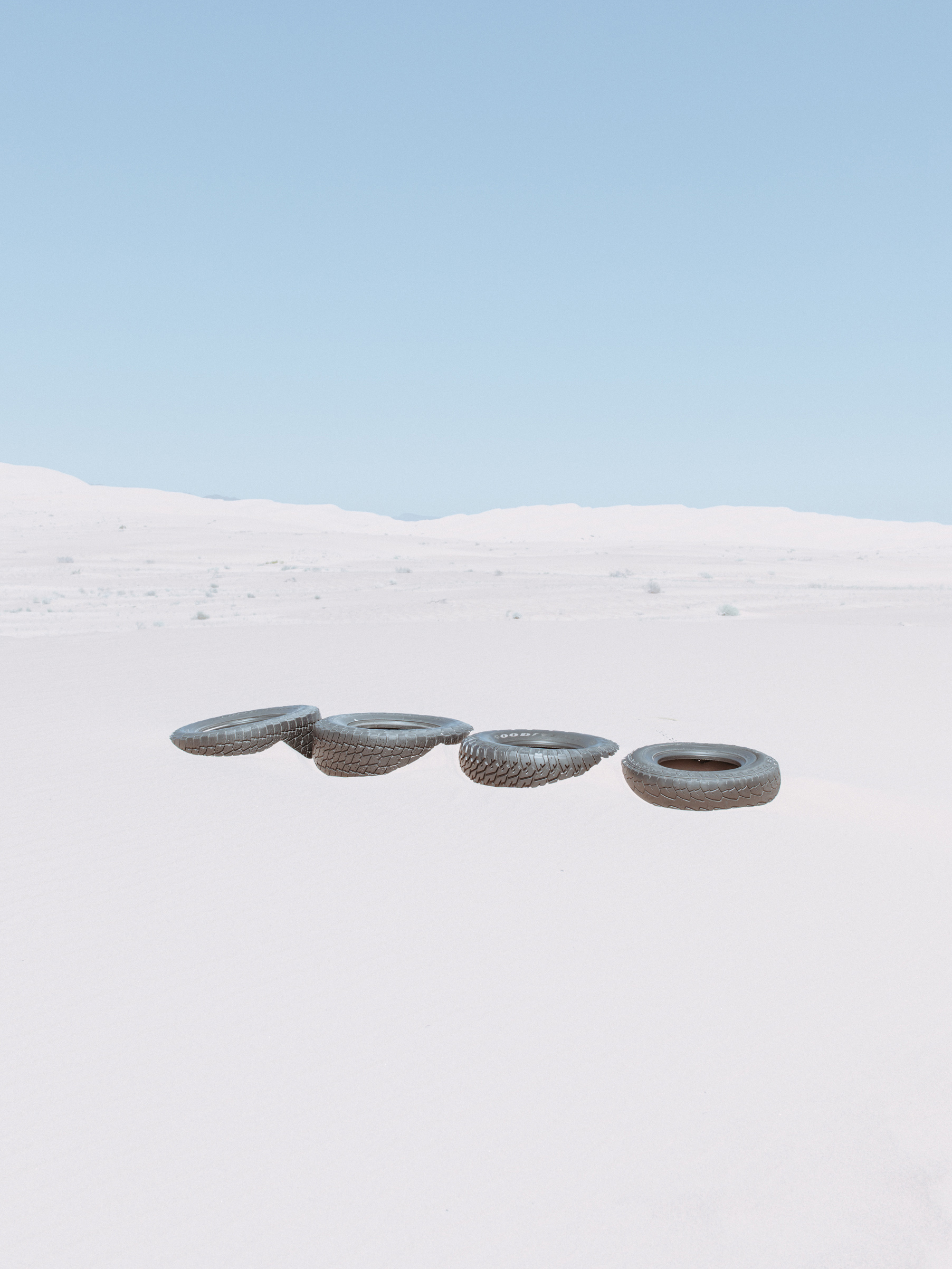

Locals largely view the result as a pipe dream that should have stayed in someone’s imagination. In some places, fencing stops short at a saguaro cactus, large boulder or country club, but then slices right through “easy build” areas: often low-income/working-class neighborhoods, public parks and wildlife preserves. (Some of the poorest counties and safest cities in the nation are situated on our southern border, where the cost-benefit equation of pouring billions of dollars into more “wall” is particularly offensive.)

In response to outcries by ecologists and conservationists about habitat fragmentation caused by the current infrastructure, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) cut a number of holes into the fencing, as if the migrating species had an area map of these caveats. Despite the common assumption of antagonism between ranchers and conservationists, particularly in rural parts of Texas and Arizona, in some areas the two groups have in fact aligned and coordinated their efforts to protect fragile desert ecosystems from the impacts of border-security measures — such as fencing, heavy vehicle use, surface clearing and the construction of levies and culverts that disrupt the natural watershed. “It used to be ranchers on one side, environmentalists on the other,” Tony Sedgwick, whose 4,500-acre ranch sits right on the border outside of Nogales, Ariz., said. “But we realized we have common goals. Ninety percent of our interests overlap.”

In certain parts, such as Nogales, Ariz., local authorities were left with a public works nightmare. Flooding worsened by these barriers killed at least two people and caused millions of dollars’ worth of damage to local business and infrastructure. Then there are the places where the fence skips a field or two, or just a few dozen yards. Unofficially, these isolated tracts of fencing are referred to as “contingency miles” — since the Secure Fence Act required counties to build barriers but not to join them up (or follow the actual border). The effects of which now impose interesting challenges on the U.S. residents who live on the “Mexican” side of an 18-foot steel bollard fence. In the Rio Grande Valley, Texas, the border fence can sometimes wander up to a mile north of the Rio Grande River, which forms the state’s international boundary line with Mexico, trapping some residents and thousands of acres of Texas land between the border wall and the legal border.

As a result of all this, a substantial number of border residents simply do not trust in the federal government’s ability to understand and responsibly manage land-use concerns when it comes to enhancing physical barriers or securing the border.

After two months, and not yet out of Texas, we began to feel that any insistence on diagnosing the pro-wall versus anti-wall binary was useless. The more the issue is forced upon these communities, the more it seems to collapse in on itself, as people refuse to give the argument legitimacy. Even Trump supporters told us “that ain’t going to happen.”

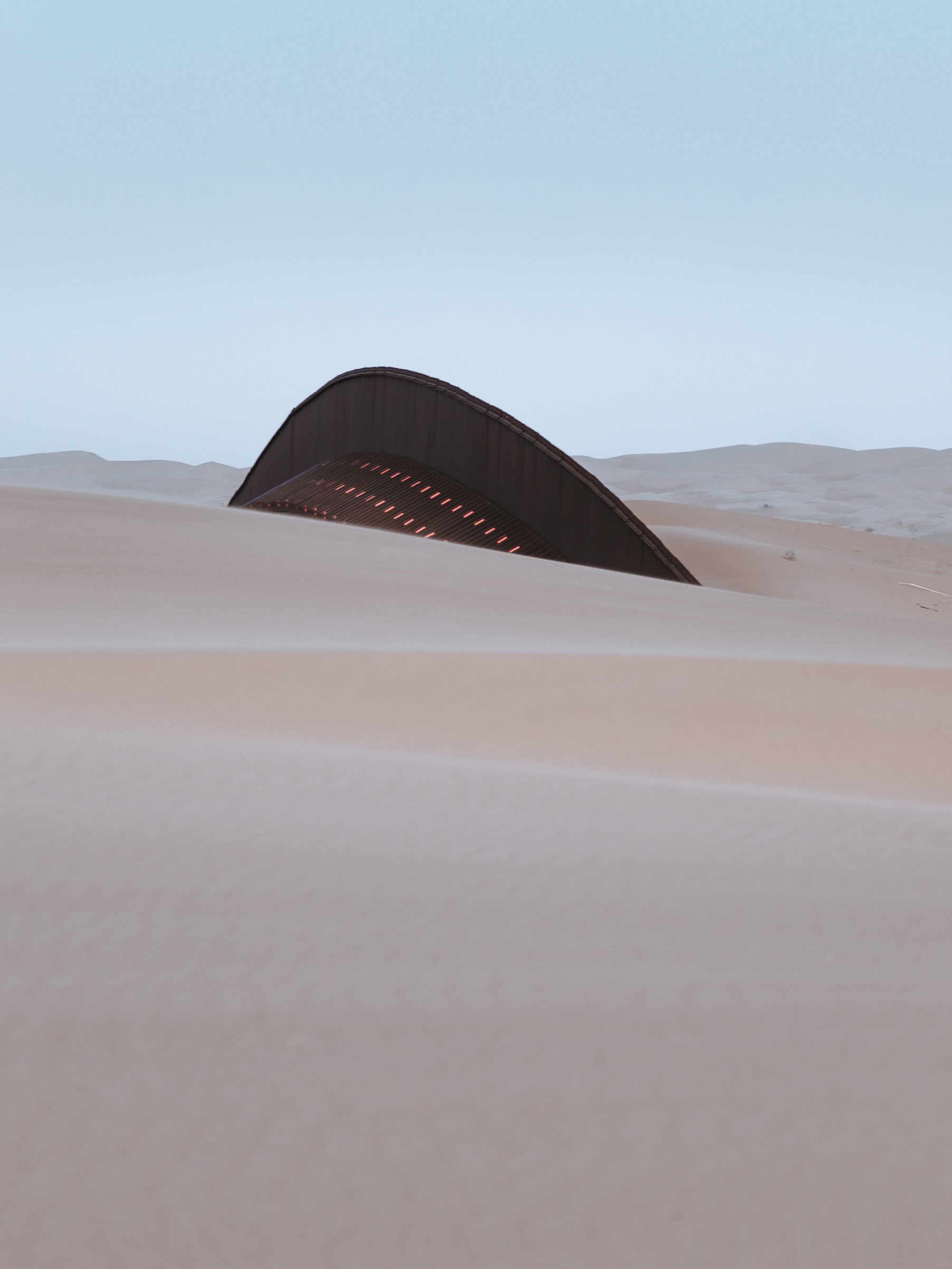

But they did have other concerns. What people commonly spoke out about, and what we observed, is the extent to which, along the border, the everyday life of ordinary citizens exists in a surveillance state. In the Rio Grande Valley, Texas, police observation towers look over the Home Depot parking lot. A father and Tejano who works at a nearby Lowe’s and lives across the road from the border wall in Brownsville said that being watched by the U.S. government on one side and the cartels on the other has made him and his neighbors both paranoid and fearful. Throughout our time in the borderlands, being stopped and questioned and sometimes searched daily — even hourly — by CBP agents became routine. Though at other times, they were oddly difficult to reach, including when Elliot and I ourselves discovered a 15-year-old Honduran boy who had crossed the border. We attempted to call CBP, only to find the number listed on their website was incorrect; when we flagged agents down, they accused us of aiding and abetting the child, whom we had given food and water. Locals also complained about a variety of other disruptive CBP practices. “The only real thing ruining the peace is the Border Patrol,” said Betty Lindstrom, whose property abuts the border wall outside of Naco, Ariz.

The presence of the CBP has increased a great deal in recent decades — which has been particularly challenging on tribal lands, where jurisdictional confusion, geographic remoteness and a long-standing mistrust of law enforcement make everything more complex. Ofelia Rivas of the Tohono O’odham Nation described a state of crisis among her people, suffering from repeated abuses and harassment at the hands of Border Protection and the destruction of their way of life, which started with their homeland being divided between the United States and Mexico.

The southern border is a cross-continental no-man’s-land, but not for the reasons commonly imagined. It’s not an empty, hostile landscape. It’s not a heavily militarized zone where violence frequently flares up between border-security agents and cartels or between citizens and migrants.

Instead, the people who live there avoid the border because its existence — and all it requires — has limited their rights. Many of them told us that building a full border wall, and therefore bringing with it an even greater government presence, may only make their lives harder.

Correction, Feb. 19: The original version of this story misstated the type of material used to mark parts of the border between the U.S. and Mexico. It was marked with railroad rail, not railroad ties.

Genevieve Allison is a freelance journalist and artist based in Colorado.

Elliot Ross is a photographer based in New York.

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision