On a recent trip to Louisiana, I sat across the breakfast table from Dr. Nicole Freehill, an OB-GYN who has been practicing for more than a decade, as she explained how caring for her patients has changed since the state banned abortion in June 2022. She described the helplessness of telling a teenage survivor of sexual assault, pregnant and desperate not to be, that there was nothing she could do for her. “There are patients where you just know from the way they’re looking at you that traveling to another state is not an option,” Freehill said. “It’s untenable.”

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, 14 states including Louisiana have banned abortion completely. What’s happening in Louisiana is a microcosm of what’s happening across America: the anguish of having a fundamental right stripped away and the resilience of people working tirelessly to help in the midst of a dire situation. Now, with the future of reproductive health care, including fertility treatment, hanging in the balance, the Supreme Court is preparing to decide the fate of one of the last remaining lifelines for people in states like Louisiana: abortion pills.

Even before Roe was overturned, pills were the most common form of abortion in the United States. A safe, effective, and FDA-approved method for ending pregnancy and treating miscarriages, abortion pills work best when taken within about the first 13 weeks. Pills can be prescribed remotely by licensed providers in the U.S. and sent through the mail without an in-person visit, which is crucial in rural areas and states that have banned or severely restricted abortion. Aid Access, an organization dedicated to providing abortion pills by mail, reports that they receive more requests from people in Louisiana than in any other state.

All of this is at stake right now, as the Supreme Court prepares to hear oral arguments in a case that could impose extreme and medically unnecessary restrictions on abortion pills. The case, brought not by medical experts but by anti-abortion activists, gives the Court a chance to override the FDA’s approval of mifepristone, one of two drugs used in medication abortion. All of this despite the fact that mifepristone has been used safely and effectively by more than 5 million people over the last two decades and rigorously tested in more than 100 scientific studies. It’s safer than Tylenol, Penicillin, or Viagra.

No matter where you live, this case should be on your radar. Restricting access to abortion pills would have sweeping implications for 65 million women of reproductive age living in the U.S.—not only in states with abortion bans, but in places like New York and California. This has nothing to do with science and everything to do with banning the most common method of abortion in the country. (In fact, in February 2024, an academic journal retracted two studies cited in a lower court ruling to restrict medication abortion, citing factual errors and “a lack of scientific rigor.”)

If the Supreme Court decides once again to advance a political agenda at the expense of people’s lives and access to essential health care, we don’t have to imagine what the consequences will be—we’re already living with them. Researchers estimate that, since Roe was overturned, there have been more than 64,500 pregnancies as a result of rape in states with abortion bans. (Louisiana, like many other states with total bans, provides no exceptions for rape and incest.) While some abortion bans include exceptions when the life of the pregnant person is at stake or the pregnancy is incompatible with life, experiences like Kate Cox’s in Texas and Nancy Davis’ in Louisiana illustrate the horrifying truth: In the moments when these exceptions are most urgently needed, they do not work.

In the last year and a half, Americans have been confronted again and again with the devastating impact of abortion bans. Brittany Watts in Ohio was brought up on charges and hauled before a grand jury for having a miscarriage. “Ashley,” a seventh-grader in Mississippi, became pregnant after being sexually assaulted by a stranger in her yard; unable to afford the nine-hour round trip to the closest abortion provider, she’s now a mom. In Texas, Yeniifer Alvarez-Glick died as a result of the state’s abortion law. Equally chilling are the stories we’ll never hear: In the first six months of 2023, there were an estimated 1,800 additional births in Louisiana, suggesting that many people who cannot access abortion in their community are left with no choice but to simply remain pregnant.

Read More: She Wasn’t Able to Get an Abortion. Now She’s a Mom. Soon She’ll Start 7th Grade.

But abortion bans are just the beginning of efforts to restrict Americans’ reproductive decisions, not the end. After the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos had the legal status of children, several fertility clinics in the state paused treatment, devastating patients whose journeys to parenthood were abruptly put on hold. Anti-abortion groups have advocated for so-called “personhood” language—like the provision in Louisiana state law declaring that “every unborn child is a human being from the moment of conception and is, therefore, a legal person”— as a path to criminalize not only abortion, but everything from birth control to IVF.

Adding insult to injury is the fact that, in a country that is already home to the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world, pregnancy care is suffering as a result of abortion restrictions. According to one study, women in states that banned abortion post-Roe were up to three times as likely to die during pregnancy, childbirth, or the postpartum period. Another study found that 93% of OB-GYNs in states that have banned or severely restricted abortion have been unable to follow standards of care because of abortion laws. Kaitlyn Joshua, a mom and community organizer from Baton Rouge, has described being turned away from not one but two emergency rooms while having a miscarriage. Terrified and bleeding through her jeans, Joshua was told by doctors that while a surgical procedure or pills could help with her pain and speed up the process, they could not treat her as a result of Louisiana’s abortion ban. “I was in total disbelief that I could live in a country that would put me in this predicament,” she said.

For Joshua, that was just the beginning. She shared her experience with a reporter and at a public forum held by the hospital. Messages poured in on social media from Louisianans denied care or told their only option would be to travel hundreds of miles to access abortion. When we met up at a coffee shop during a break in her Saturday errands, she bounced her four-month-old baby on her lap and told me she is determined to keep speaking out: about the devastating impact of abortion bans, about the barriers to care faced by Black women in the South, and about why anyone who can get pregnant should read up on abortion pills. “You never know when you might need them,” she said.

Spend any amount of time in Louisiana, or any state that has banned abortion, and the growing divide between the ideology of those in power and the will of the people they represent becomes painfully clear. A majority of Americans, including a majority of Louisianans, believe abortion should be legal. Two-thirds of Americans want abortion pills to remain accessible, including more than half of Republicans. A poll a year after Roe was overturned found that one in four Americans said state efforts to ban or severely restrict abortion have made them more supportive of abortion rights, not less. Every time voters have had the chance to decide on this issue, abortion rights have won.

Read More: Doctors Are Still Confused by Abortion Exceptions in Louisiana. It’s Limiting Essential Care

When the Supreme Court overturned Roe, it was like a match on dry kindling. There were hundreds of protests in the weeks that followed; some called it “the summer of rage.” More than one pundit wondered whether women in America could possibly sustain that level of fury for the long-term. A year and a half later, it’s clear: We can and we will.

After all, it’s outrageous that nine unelected Supreme Court justices, not one of whom has spent a single day in medical school, are once again in a position to determine the rights and futures of millions of people. It’s infuriating that so many of the Republican politicians pushing for a national abortion ban—including likely presidential nominee Donald Trump—are permitted to spout myths and misinformation without ever having to answer for the cruelty inflicted on people all over this country. And it’s unconscionable that anyone who does not want to be pregnant or have a child—for any reason—would not have the freedom to make that decision on their own terms.

On a sunny Friday in January, Petrice Sams-Abiodun, Vice President of Strategic Partnerships for Planned Parenthood Gulf Coast, walked me through the beautiful New Orleans health center, newly opened in 2016. The waiting room was bright and airy, with private spaces for patients who need a few minutes to themselves and shelves of children’s books for anyone who shows up with a toddler in tow. She showed me the rows of exam rooms, the state-of-the-art lab for test results, the paintings by local artists on the walls—and the extra-wide hallways, surgical sinks, and restrooms built to exact specifications to comply with the state’s targeted restrictions on abortion providers. The state refused to grant Planned Parenthood’s license to provide abortions, and then Roe fell, and the point became temporarily moot. Sams-Abiodun pointed out the recovery room where patients could rest after an abortion, comfortable recliners still in boxes, dust gathering on the state-mandated nurse’s station. “This room makes me the proudest and the angriest,” she said.

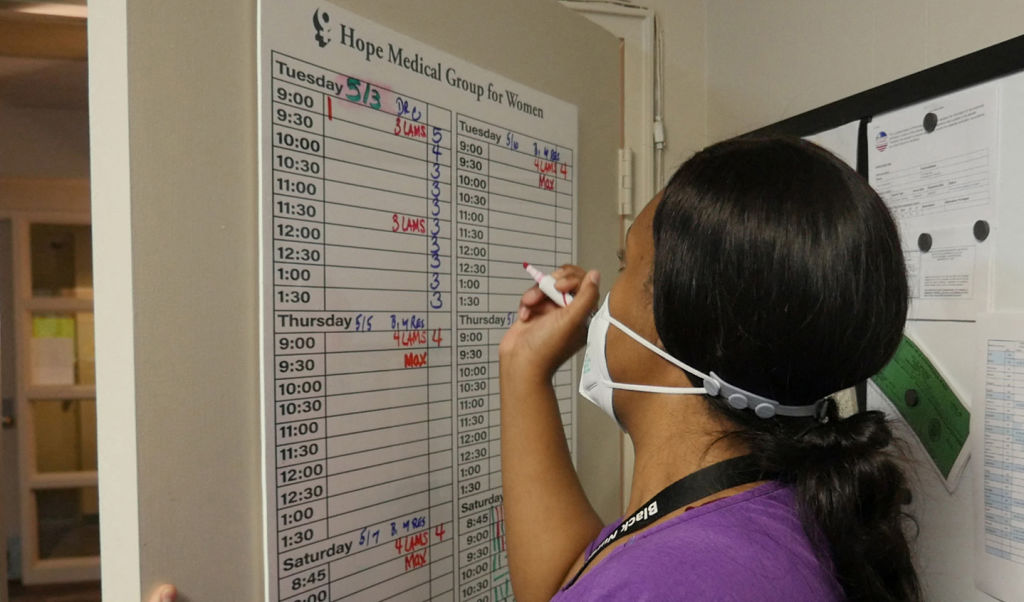

The truth is, it’s not enough to stay angry. We need to channel our rage into action. And in Louisiana and across the country, Sams-Abiodun and so many others are doing exactly that. Abortion funds are gathering resources to help people travel out of state. Activist networks are helping connect people to care, including abortion pills by mail. Health care providers are sounding the alarm about the crisis unfolding before our eyes. Legal groups are litigating on behalf of abortion seekers. Organizers are working tirelessly to spread word about what’s happening, from state legislatures to the highest court in the land. People who have never considered themselves “political” are signing up to volunteer for candidates and campaigns. Local and national journalists are doing extraordinary, powerful reporting. Everywhere I go, people are sharing their own stories, and doing brave, important work in incredibly tough circumstances. Because when the alternative is giving up on entire swaths of the country, there’s really no alternative. “It’s like walking through the mud,” one clinic staff member told me. “It isn’t easy, but you just have to keep going.”

Cecile Richards is the co-founder of Charley, a chatbot that provides information about abortion options in every zip code in the U.S., and a co-chair of American Bridge 21st Century. She is the former president of Planned Parenthood Federation of America, New York Times bestselling author of Make Trouble, and a 2011 and 2012 TIME 100 Honoree.

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders