Soroka Medical Center is about 25 miles from Gaza. It is the hospital that took care of most of the wounded after the Hamas terrorist attacks on October 7th that claimed the lives of more than 1,400 Israelis.

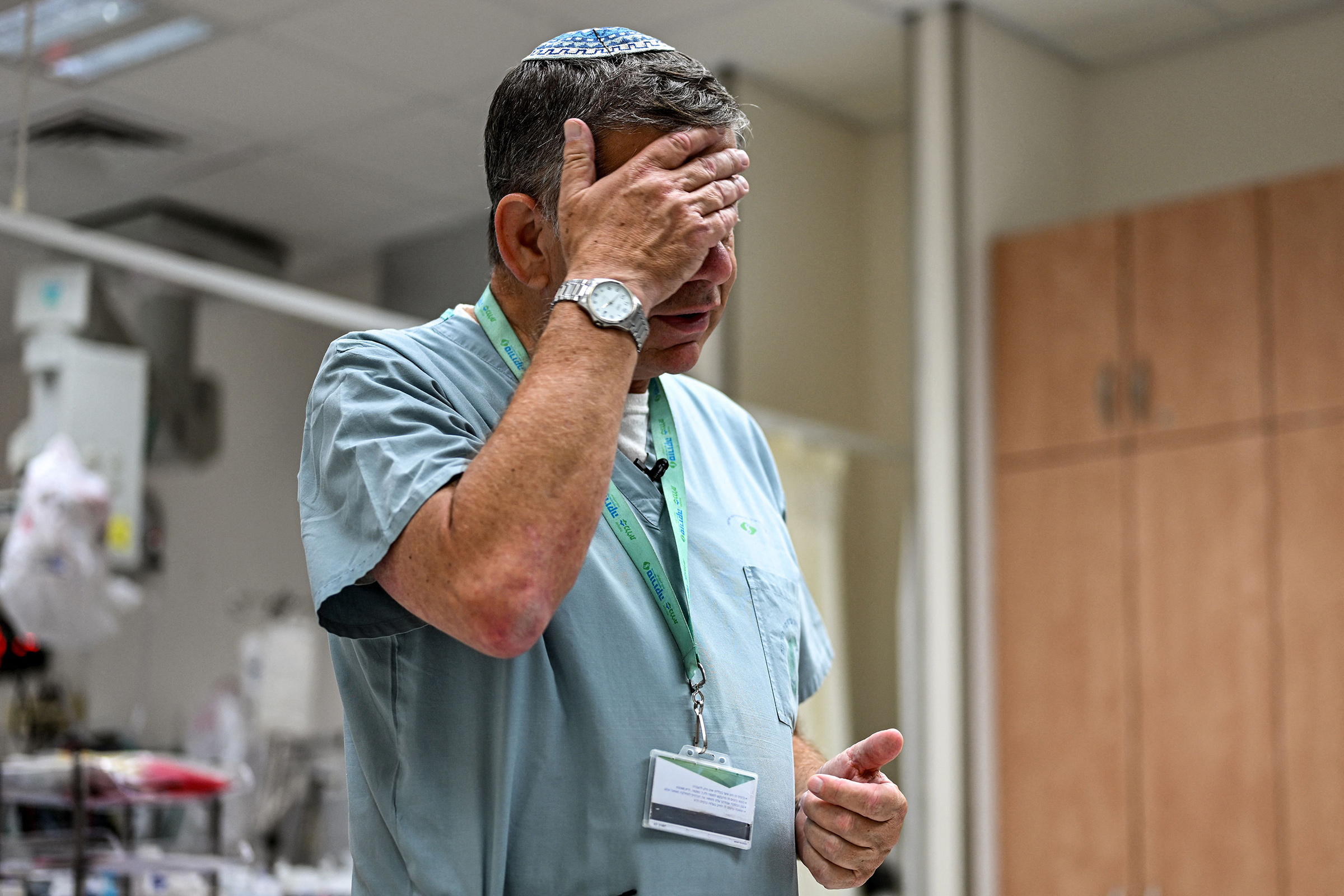

The head of the hospital, Shlomi Codish, described how his staff approached one of the largest mass casualty events due to a terror event in history. What they went through should be required reading for every member of the international medical community.

In the first 16 hours, the Soroka emergency department treated 680 patients, 120 of whom were critically wounded. As victims started arriving, the hospital discharged at least a hundred patients to make room. They activated staff, many of whom were off because it was a Jewish holiday.

“This means people are now expected to get into their cars and drive to the hospital while air sirens are going off around them,” Codish said. They left behind their families, not knowing if their loved ones would be alive when they returned, or if they would return themselves. Still, “everyone has an enormous sense of duty. People just did what needs to be done to get to the hospital and save lives.”

One of the first patients requiring surgery was a pregnant woman who was at full term. She was shot in the abdomen multiple times. “Reading the surgical report describing gunshot woods extracted from an unborn infant is beyond what the human mind needs to hear or know about,” Codish said, describing the injuries as being due to “shooting at point blank.” The mother survived but her baby died.

Codish told me about other patients his team cared for. A young woman shot in her pajamas. A child with four gunshot wounds. There were twin babies found in a house by the army many hours after the attacks on that kibbutz ended. They were hidden in a safe room, unharmed but suffering from dehydration; their parents were lying dead just outside. This was like the stories he heard from World World II, Codish said. “Let’s protect the children in a sheltered room and expose ourselves to the terrorists, so we get killed and they don’t.”

Then there are the patients they didn’t see. “Someone asked me if we saw rape victims,” Codish said. “We didn’t, because the rape victims were kidnapped or killed, and they didn’t make it to the hospital.”

While they resuscitated and operated on patients, doctors, nurses, and other staff didn’t know whether they would be safe themselves. “When the rockets started going off, we had to move several wards that were not sheltered into sheltered area,” he said. That day, according to Codish, 42 air raid sirens went off to warn of incoming rockets. Of these, 18 targeted the hospital area.

The healthcare workers also knew that the people they were treating could be their neighbors and, in some cases, their own family members. Over 90 percent of their staff lived in areas that were attacked. Among those murdered were two physicians and two retired nurses. Many staff members lost first-degree relatives. And a Soroka nurse was kidnapped and believed to be among the over 240 hostages held by Hamas.

One of the doctors killed was Daniel Levy, a 34-year old resident physician undergoing specialty training in ear, nose, and throat surgery. He lived with his family in Kibbutz Bari. When the attacks started, he put his wife and children in a bomb shelter and rushed to the local clinic to care for the wounded. But the clinic was taken over by terrorists and he was shot dead, along with nearly all the clinic staff and patients.

“This is a medical clinic marked clearly as such, where people were caring for injured people, and they were executed within it,” Codish said.

Since the tragic events three weeks ago, administrators at Soroka Medical Center have been working to increase their clinical capacity. They are training clinicians who don’t normally treat trauma patients, like internists and pediatricians. They have increased the number of beds in the intensive care unit and are building a new rehabilitation ward “because we now have hundreds of patients who require rehabilitation, far beyond what we ever needed before.”

There is a lot to learn from Soroka’s healthcare workers. First, emergency preparedness experts can draw from the rapidity of their response in activating protocols, mobilizing staff, and triaging and treating such a high volume of patients, all of which were especially remarkable given the dangers to the staff themselves.

Second, the courage of healthcare providers and the necessity of putting aside their own feelings in the moment does not mean that they are immune to the aftermath. “All of this is hitting home very, very horribly,” Codish said. “We all saw sights we haven’t seen before, and horrors beyond anything we’ve previously expected.” He expects that the trauma “is something we will be struggling with probably for years to come.”

Third, while all healthcare professionals are trained to treat suffering and many hospitals prepare for mass casualty events, there is something very different about the targeted savagery they had to bear witness to. Anyone who struggles to understand the pain that Israelis are going through should remind themselves of what these clinicians encountered. This is not to take away from the very real suffering Gaza civilians are going through in the midst of Israel’s retaliation against Hamas. But the world can never forget, and should never attempt to justify, the unfathomable brutality of the October 7th massacres.

The international medical profession must pay particularly close attention. After all, as Codish warns, terrorists capable of these kinds of atrocities could inflict this pain elsewhere, too. “People must understand that what happened in Israel today could happen in Paris, London, Washington, or New York tomorrow.”

Dr. Wen is an emergency physician, public health professor at George Washington University, and nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. Previously, she served as Baltimore’s health commissioner.

Updated: A previous version of the piece spelled the name of the hospital head incorrectly.

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time