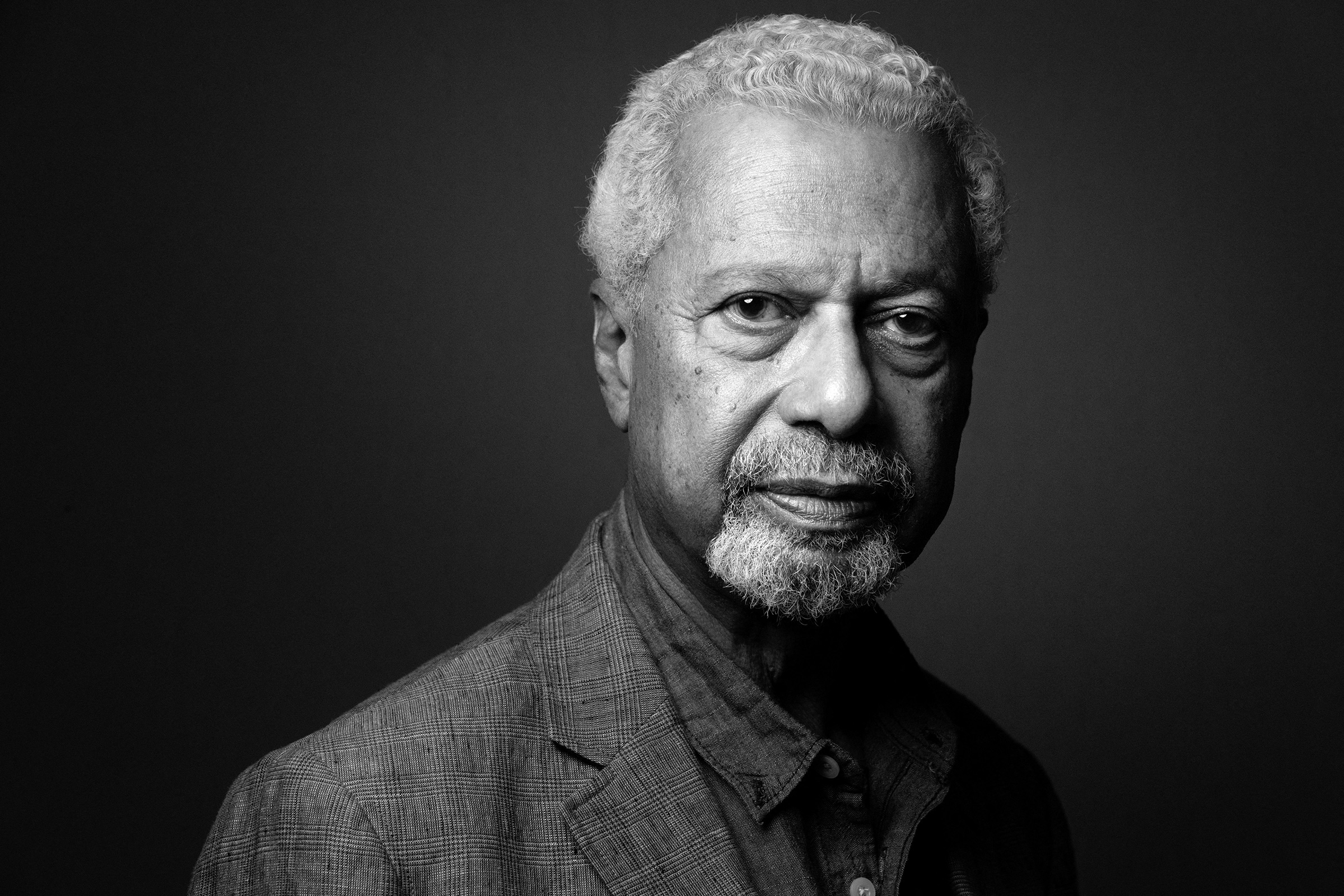

Nobel Laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah left his homeland—the island of Zanzibar—during the revolution and upheaval that followed the end of colonial rule on the island. For nearly forty years, his novels have explored the effects of colonialism and displacement on the human spirit. He spoke to me from his house in the United Kingdom to mark the republication in the U.S. of his landmark works: Desertion, Afterlives, and By the Sea. He told me why the movement of refugees and migrants from the global south to the global north today cannot be separated from the injustice of colonialism.

Angelina Jolie: It is such a pleasure to meet you. I’m so grateful you would speak with me.

It’s a pleasure to meet you and to do this.

You’ve had a resurgence of discovery—many people rediscovering you and your books.

Well, that’s what the Nobel Prize does, I guess. Whatever we say about prizes, if you’re looking at the positives, it suddenly brings us this person whose work has been happening for decades, but we’ve never heard of it.

And you’ve been teaching and writing for so many of these years?

It was always what I wanted to do, and the two things are self supporting. It’s not because you need to be an expert in teaching literature in order to be a writer. But I think you’re better informed about writing because you’re a teacher of literature, and possibly a very informed teacher of literature because you’re a writer.

Read More: Nobel Laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah Urges Us Not to Forget the Past

So much of what I see in your work is about the human connection. I’ve spent a lot of time with refugee families, trying to understand what causes displacement, what it is to lose your homeland. I haven’t had to experience that, but I’ve met many people who have, and I know your work speaks about that.

There’s nothing new about this phenomenon of large movements of people. The nastiness that is part of human societies constantly creates situations where we have movements of people who have to seek safety somewhere. This is what people have done, say, from Europe, to the rest of the world, [in the past]. In our current world, the movement of people is [now] mostly from the formerly colonized territories of the world, colonized by European nations and European powers. When people are in need, they go to places where it’s safe. So it’s no surprise that the movement now is this way, heading from these formerly colonized places. When people turn up then there is an obligation to say, at the very least, ‘How can we help you?’ And if we don’t want to help [them], we can say, ‘I’m sorry, now you have got to go back.’ But not to detain people and to treat them as if they’re criminals.

You mentioned that many of the places where people are fleeing have a history of colonialism. This dawned on me while I was working with the UN‚—and I chose to leave at a certain point. It would be hard not to sit in a place where there was displacement and poverty and conflict and think, had these people had the ability to trade more fairly and different other kinds of support, there wouldn’t be this level of conflict or poverty or displacement. This kind of loop comes back in aid relief. It’s really quite hard not to see [it], and not to be very upset by it.

You’re being very careful in how you’re framing this. But I don’t have to be as careful as you. European colonialism—particularly in Africa—transformed everything from top to bottom: borders, cultures, education, nations. And for most countries it’s been 50 years, and still the legacy of all of that is completely unsorted. What I dislike the most [is] this kind of narrative of criminalizing people who are actually attempting to do what you and I would have done, and what I did, and to try and find a better place—a safer place—to live. I don’t think this is the most humane way to respond to these issues.

I know you were 18 when you fled.

I was 18 when I left. I don’t like fled.

How do you make the distinction?

My life was not at risk. I wasn’t in danger of being locked up, of being killed, unlike some of the people that we see, from Syria, from Afghanistan. I left because I wanted a better life, because I wanted to study, and because they closed the schools. I was 18. And I said, ‘I’m not having this.’ But it isn’t because I fled. I wanted to start a new life.

That is one of the themes of your book Desertion. How did it come about?

I was thinking about the absence of stories about relationships or love between Europeans in the colonial world, and in our case, in the case of [Zanzibar]—people who lived along the coast. It would have been unthinkable for European women to have a liaison with a local person in our part of the world during the 19th century. But for sure, because men are more kind of freewheeling in this way, there must have been relationships—perhaps even equal relationships, not just dominating or horrible relationships. But why have they not written about it? That’s what started me off thinking about how that might have come about, because I know it I did. You’ve seen the film Out of Africa?

Many years ago.

AG: In the funeral scene, you see a picture of this woman, mostly covered up but you just know that she’s a Somali woman. Who’s that? The answer is, that was his mistress. It’s not in the novel. It’s not in Out of Africa the memoir. That was in the next book that [Karen Blixen] wrote, a series of letters. That was one of the few references there is to the possibility of such relationships. There were such relationships that were not spoken about or written about. That was the first thing that interested me. A liaison like that would have been disapproved of from his side, you’re thinking of a European man. It also would have been disapproved or from our side, because [it] seem[s] like a kind of prostitution: Why are you messing around with these people who don’t have any respect for us? There would have been consequences.

And would desertion have been one of these?

AG: The way I was thinking about it was, there are multiple forms of desertion, like the lover [in the novel] leaving, because that’s what a European man was likely to do, or the two brothers, [when] it’s clear that one of them is going to leave. The other one does not intend to leave. It was a way of exploring all those issues about consequences. Decisions about affiliation: How faithful should you be? Should you be faithful to the community you’re born in? Or should you seek something else somewhere else?

Is that why you continue to often write about Zanzibar?

I don’t know if I am always in a position to choose what I write about. For many writers, the landscape that you explore is probably a fairly limited one that is informed by your experience, and your knowledge. But ultimately the things that engage you probably don’t change that much. I find myself trawling the same little landscape.

Jolie is a contributing editor at TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders