As a curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Eleanor Nairne is very particular about how an artwork should be placed. “I always say that you have to ask the work if it’s sat comfortably,” she says. “The work will tell you if it is or not.” So it is that on a Tuesday in October, when the museum is closed, Nairne is having one of her most stressful workdays ever, supervising the placement of 288 delicate, diaphanous metal forms not on a wall but hanging from a 41-ft. ceiling with the aid of four rented scissor lifts, a team of installers, layout instructions in the form of a floor plan and a 3D rendering, and a lot of filigree thread.

Complicating things is that the artist is not present. This is excusable because he is 80, lives in Ghana, has had work unveiled in more than 20 exhibitions this year in cities as far-flung geographically and culturally as Shanghai, London, Dubai, and Lagos, and is quite possibly the most in-demand visual artist alive today.

Rarely has a cultural figure had such transcontinental acclaim as El Anatsui, the creator of the Philadelphia museum’s newly commissioned work. His success is even more unusual because he’s based in Africa, which lacks the East’s and the West’s well-resourced mechanisms for promulgating their creations. But Anatsui often talks about his art in terms of the “nonfixed form,” a reference to both the literal malleability of his monumental works and their adaptability to the space—and culture—in which they are placed. His art is as resonant in Singapore as it is in Switzerland.

Anatsui’s most famous artworks, colossal wall hangings made of linked-up tiny pieces of metal, defy easy categorization. Cascading draperies of color and contour, they have the visual drama of paintings, the pixelation of mosaics, the complexity of weaving, the curves of sculpture, and the grandeur of architecture. “They don’t quite look like anything that people have seen before,” says Nairne. “His work feels so unusual and dynamic as a material experiment.”

Most people have settled on describing them as tapestries or quilts, partly because those are the closest things the Western art traditions have to his giant, supple swaths, and partly because the amount of close-up handiwork that goes into making them is similar. Instead of thread and cloth, however, Anatsui uses the metal lids and neck coverings of liquor and other drink bottles, which are flattened and twisted into various shapes, and then linked together with wire. Bottle caps, Anatsui has observed, “have more versatility than canvas and oil.” He has spent decades experimenting with their capacities.

For the work in Philadelphia, Anatsui is trying something different. Rather than one gargantuan aluminum waterfall, he’s twisted the metal security seals from bottle necks into a material more like a net, which has then been cut into ghostly shapes and suspended from the ceiling, so that from some vantage points they look random, from others they look like a milling crowd, and from others they cohere into a unified whole. “He abandoned the wall. And in doing that, and stepping out into this void, he’s creating something that feels very exhilarating,” says Nairne. “And when we see a person who is an octogenarian doing that, that feels especially exciting.”

Famously, Anatsui almost literally stumbled across the idea of using bottle tops when he found a discarded bag of them on the road in Nigeria in 1998. It lay around his studio for two years while he continued to experiment with other discarded materials, including the cheap wooden trays locals used to display fruit at a market, disks from opened cans, and wooden pestles, doors, and window frames. He also worked with pot fragments, grinding them up to make the raw material for new clay that he adds to clay fresh from the earth. “Life is not a fixed thing,” he has said. “It is something that is in constant flux. And therefore I want my artworks to have some element of that in them.”

It’s possible Anatsui’s facility for gathering what he needs and then working with it was forged during his upbringing in Anyako, a fishing community that juts into the Keta Lagoon near the border with Togo. His father was a weaver and a fisherman, and Anatsui, the youngest of 32 children, grew up surrounded by people doing such repetitive and ultimately meditative work as weaving and mending nets. When his mother died, he was sent to live with an uncle who was a Presbyterian minister, and from there to study sculpture at an art school that largely revered the Western canon. But Ghana was gaining its independence from Britain during Anatsui’s formative years, and he became interested in Ghanaian music and culture. Throughout his work there’s a sense of reclaiming, a notion of rediscovering and reincarnating that which is local.

Hence the bottle caps: they’re cheap, abundant, brightly colored, and a staple of the landscape. Equally importantly, they are loaded with history. Anatsui often refers to the cycle of trade that ultimately brought so many of the caps to his environment: that Africans were taken by force through Ghana to labor in the plantations to produce sugar and rum that was shipped to Europe and then sent to Africa. “The drink represented here by bottle caps links all three continents,” he has noted.

In 1975, Anatsui got a job teaching at the first Indigenous university in Nigeria, in Nsukka, and set up a studio there. His sheets, as he calls them, came to Western attention largely through a 2002 exhibition in Llandudno, Wales, that was so popular it traveled to nine other places in Europe and the U.S. By 2007, he earned the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the Venice Art Biennale. As his fame, and prices, started to grow, he employed local townspeople and students in Nsukka to help him keep up with the supply chain and the handiwork.

In 2021, he built a much bigger facility near Accra, and now has operations in both countries, gathering and preparing many of his bottle tops in Nigeria and assembling the works in Ghana. “A whole generation of West African artists and creatives stand on El Anatsui’s shoulders, partly through his groundbreaking works, but partly through his model of always giving back to the communities that formed him,” says Lesley Lokko, the Ghanaian Scottish architect who is founder of the African Futures Institute, and was the director of the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Anatsui’s community-based, organic way of working has enabled him to have a much wider reach than artists who make work on their own. But it’s also key to the organic nature of his practice. He doesn’t usually sketch his designs in advance, “I let the material lead me,” he has said. “If it can’t say something, then it better not be made to say it.” After all, he once noted, “trees grow without a blueprint.” And he likes to give curators like Nairne the freedom to add their own input in how a finished piece should be installed.

Not being at the museum to supervise (except sometimes via Zoom) is fine with him. Anatsui is not overly precious. He likes the way each human hand makes things a little differently. “As an artist I have to decide how to harvest those differences into something organic,” he has said. Each piece reflects the accumulation of the unique abilities of each local craftsperson who touched it—from Accra to Philadelphia.

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

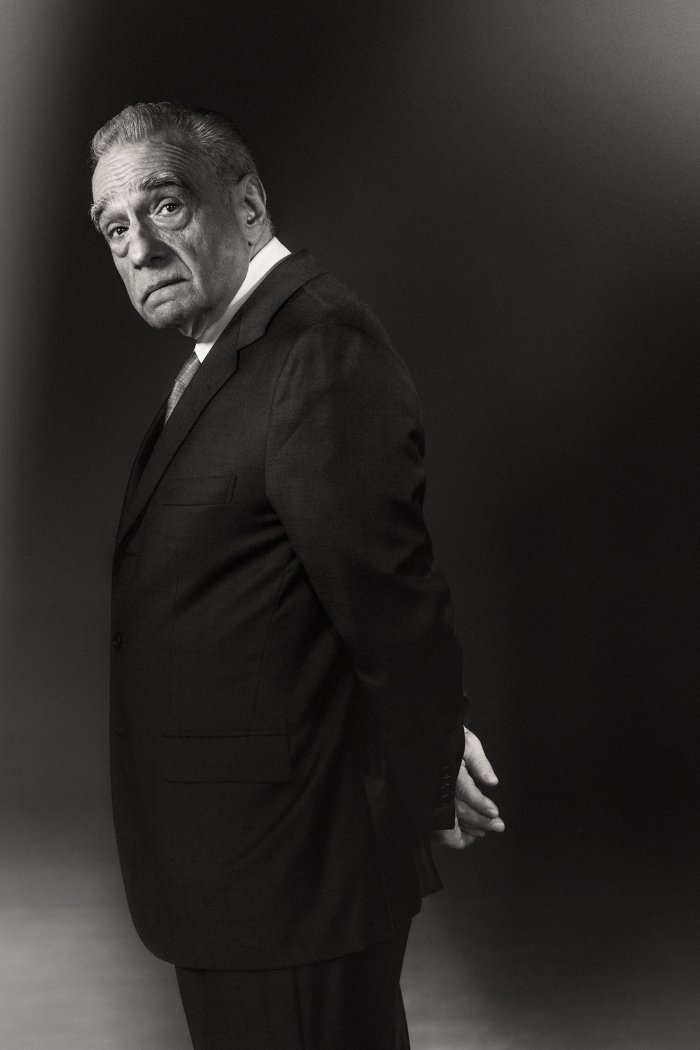

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness