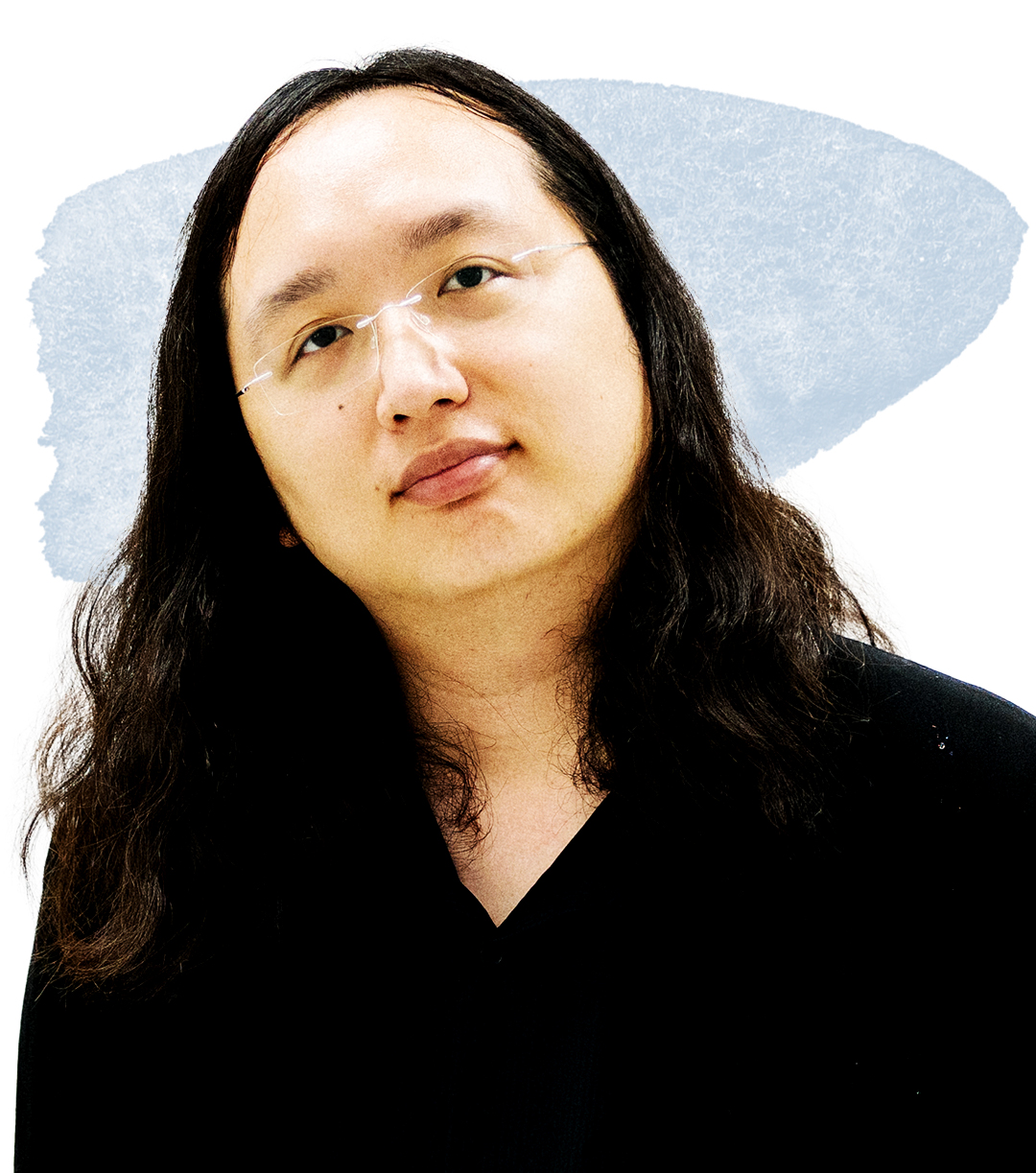

As Taiwan’s first-ever Digital Affairs Minister, Audrey Tang has her work cut out for her. Since assuming her role in 2022, the civic hacker turned government official has been grappling with not only ensuring Taiwan’s digital resilience, but also the fraught task of navigating both the risks and opportunities that AI poses for the island’s fledgling democracy.

While many politicians are focused on shielding democracy from the worst aspects of AI, Tang is experimenting with how to use it to enhance democracy—particularly in terms of AI regulation. Earlier this year, she collaborated with the Collective Intelligence Project policy organization to introduce Alignment Assemblies. The online forums enable ordinary citizens to weigh in on a wide array of issues, including the uses, ethics, regulation, and impact surrounding AI. Using a chatbot akin to ChatGPT, participants are prompted to engage with different arguments and ultimately share their views through a survey, which asks users to say whether they agree or disagree with statements such as “AI development should be slowed down by governments” and “I think we will have to accept a lower level of transparency than we are used to, but that this will be worth it given the gains AI offers.” (They’re also holding in-person conversations in cities around Taiwan.) This kind of collaboration “makes deliberative democracy more scalable,” Tang says. “And also it makes the AI development more democratic in that it’s not just a few engineers in the top labs deciding how it should behave but, rather, the people themselves.”

Taiwan has used this kind of consultative approach to governance before, most notably during its 2015 public consultation over regulating Uber, which ultimately incorporated the public’s recommendations into government policy. Tang has made that kind of rough consensus, civic participation, and radical transparency—Tang’s meetings are often recorded, transcribed, and uploaded directly to the Ministry of Digital Affairs’ website; ours was no exception—central pillars of her governance.

“If any community feels that the current path of AI somehow causes harm, causes what we call epistemic injustice—maybe they are Indigenous nations, maybe they have ways that are different from the current mainstream AI’s training assumptions, maybe they have different social norms—then there needs to be a way for them to, like what we did around Uber, come up with the rough consensus,” Tang says. “Then we can retrain AI models or work with the AI service providers to tailor-make the kind of AI that fits the local people’s needs instead of asking local people to adapt to whatever mainstream AI is doing.”

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time