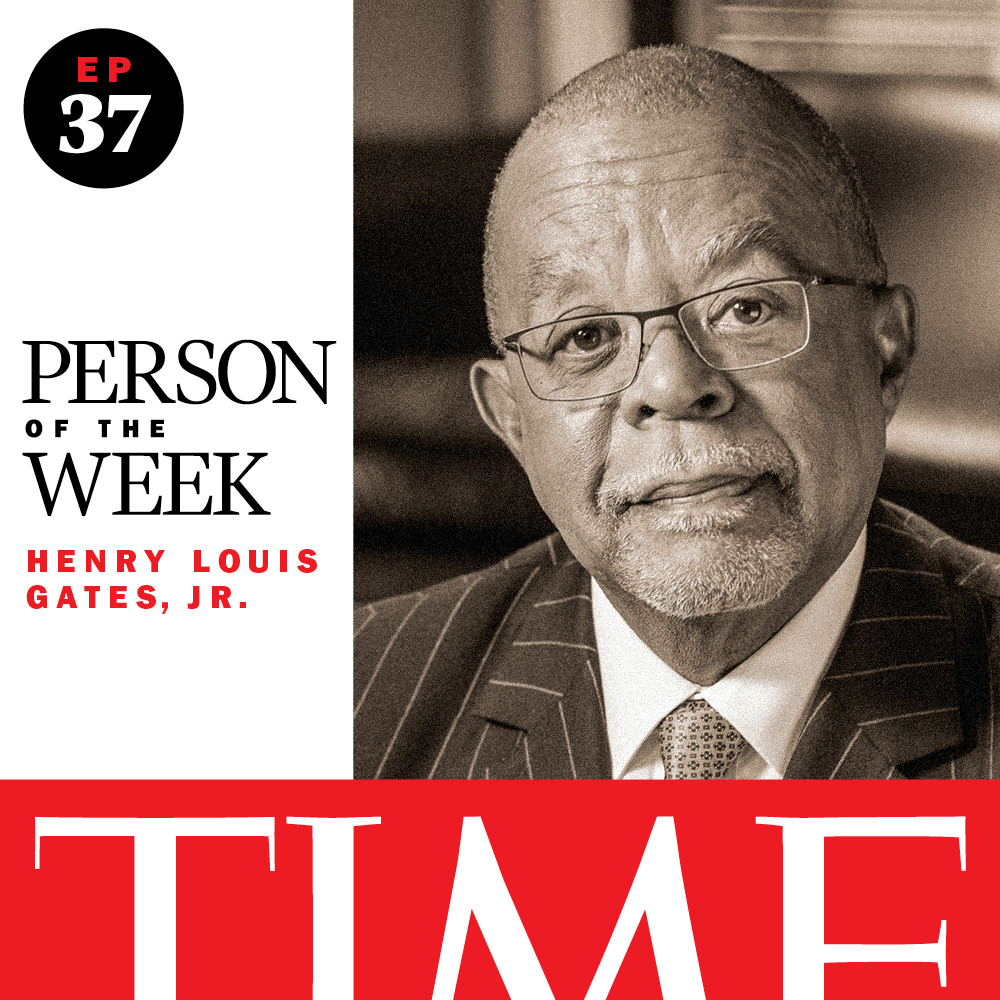

Henry Louis Gates Jr. is one of the most influential scholars of Black history and literature in the United States. He’s the director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University, author of more than 20 books and creator of more than 20 documentaries, host of the groundbreaking genealogy series Finding your Roots, and, as it turns out, my former professor.

But he’s also, really, America’s professor. And his work is foundational to how Americans understand race as part of our shared national story.

He’s won an Emmy Award, a Peabody Award, and an NAACP Image Award—all for his documentary series, The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross. And now he has a new book, The Black Box: Writing the Race. It’s a literary history of how we understand race in America, and tells the story of Black self-definition through writers—from Phillis Wheatley to Frederick Douglass to James Baldwin‚who have used literature to build Black identity in the face of racist oppression.

Throughout our conversation, I was reminded of how Professor Gates really is always looking for that teachable moment. He opened up about what it was like to grow up in West Virginia in the early years of school desegregation, why Finding Your Roots became the show it is today, and how his genealogical research has taught him that all of us are more alike than we are different.

Tune in every Thursday, and join us as we continue to explore the minds that shape our world. You can listen to the full episode here, but here are a handful of excerpts from our conversation, which have been condensed and edited for clarity.

On growing up during the Civil Rights movement:

I started school on the last day of August, 1956, in what we called, ‘the white school,’ and I went to an integrated school for 12 years. And I was treated like a little prince. My brother, Paul is five years older, and he had been in ‘the white school’ a year before I started school. And he’s brilliant, and he was just knocking it out of the park. So they knew that I was from a smart family, but even more important was everybody in that town knew everybody else.

And my parents were widely, deeply respected. My mother was very active in the PTA. As soon as that school integrated, she was there. And in 1957, in second grade, she was elected the first colored secretary of the Piedmont PTA. And that was a moment in civil rights history in Piedmont, West Virginia. And all the Black people in town, mostly the women, on the evening of the PTA meeting, they would all get dressed up and they would go over to the high school just to watch my mother read the minutes…

But look, there, there were racist strictures: we couldn’t sit down in the local hangout called The Cut Rate. The white kids could sit down. We had to order at the counter and we got our food in, you know, take away plastic cups and paper plates. And it drove us nuts. And we couldn’t date white girls. That was a big thing that we were told. The Black girls couldn’t date white boys and the Black boys couldn’t date white girls. So what that meant when you hit puberty is that all the white girls thought about Black boys and all the Black boys thought about white girls.

On why genealogy can help cure loneliness:

I find that the people most interested in genealogy are middle aged. Maybe 50 plus, let me generalize and say 50 plus. Why is that important? It’s important because at that age, you’re experiencing senses of alienation, loss, grief. You know, your parents probably are gone. Sometimes your friends are gone. Family members are gone.

Genealogy allows you to find two sets of ancestors, new ancestors in the past, new family members in the past, and through the wonders of DNA analysis, new relatives in the present. So that precisely when your family is shrinking, you can expand your sense of family back in time, vertically and horizontally.

On whether we’re in an era of racial backlash right now:

I think that we are in an era of backlash, but it’s a backlash generated by fear. The working class people with whom I grew up, thought that to paraphrase Martin Luther King (who was paraphrasing someone else) that the arc of the economic universe was long and bent up, bent positively. And nobody believes that anymore. And in my town, the paper mill that provided everybody virtually with a good life is not only gone… the physical plant had just been destroyed. And you know, it made me very, very sad. And it symbolized concretely what had happened economically, materially, spiritually, to my wonderful little hometown.

So when you feel that the rug has been pulled out from under you, that all of the certainties that you were raised with are gone, and you look around and you see there are all these Latino migrants and all these Black people…You can’t watch a commercial on TV without seeing an interracial couple. And then regular people say, what the hell is that about? What happened to good old white America, you know?

So people lash out because they’re afraid, and you can’t assuage someone fears by bullying them. You have to speak to their fears. So under those conditions, two kinds of leaders arise. Those like Barack Obama and Joe Biden, who are very sensitive and speak to fears. And those who exacerbate fears like Donald Trump.

And I’m not trying to be partisan here. It’s just a fact. And I think that Donald Trump’s popularity is dependent upon exacerbating those fears. It’s like: if you elect me, I’m going to get rid of all these immigrants. I’m going to build this big wall. I’m going to take all these bad books out of these schools. And I’m going to make life like it was in the fifties when you were watching Ozzie and Harriet and Leave it to Beaver.

And a real leader would say: ladies and gentlemen, I love that world. That world produced me, but that world is gone.

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time