Hydropower is the world’s biggest source of renewable energy, generating about 16% of the global electricity supply. And it will continue to play a key role as the world looks to meet net-zero targets, not least of all because, like a battery, it can store massive amounts of energy for later and quickly release it in moments of peak demand.

But despite being better for the climate, it’s becoming increasingly clear that renewable energy sources can have a negative impact on the environment. Just 37% of the world’s 246 longest rivers remain free-flowing—without any human-made dams, reservoirs, or other structures controlling how and when the water moves—according to a 2019 Nature study by a group of international researchers led by McGill University and the World Wildlife Fund. Not only can hydropower disrupt local communities, but it can also impact ecosystems, water quality, and biodiversity. One in five fish, for example, that passes through a conventional turbine suffers fatal injuries, according to a team of researchers at the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries in Germany. This can have especially damaging effects on migratory species, like salmon, sturgeon, and eels, whose spawn may have to travel through these dangerous downstream routes to get to the sea.

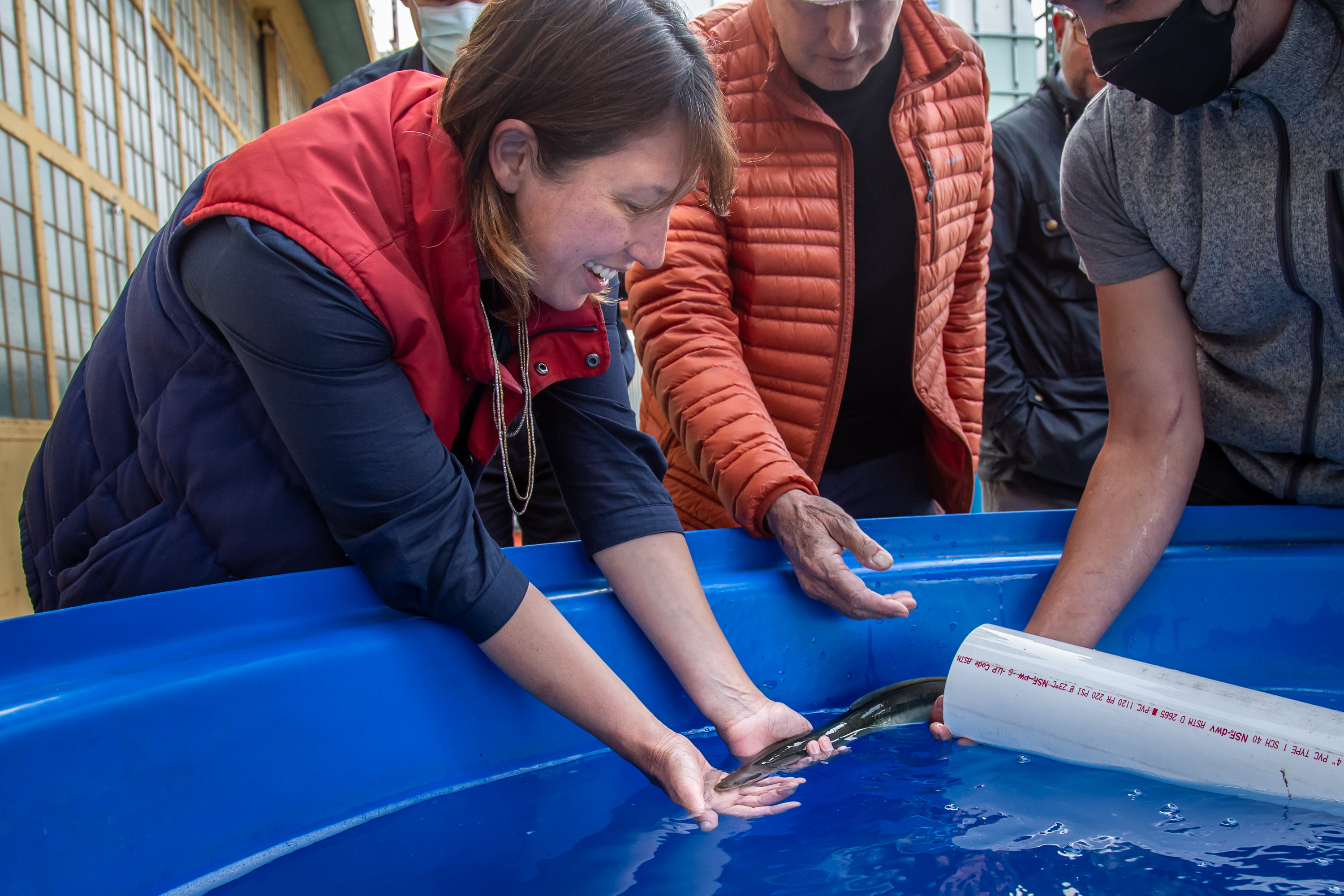

Siblings Gia and Abe Schneider, however, are trying to change this. They founded the company Natel Energy in 2009 to make sure that hydropower is rolled out in the most sustainable way possible. The company created what they say is a fish-safe turbine, and their approach is to modernize existing hydropower plants with their turbines to allow fish to pass safely, while also building new, low-impact run-of-river projects that don’t require dams, which make them as minimally disruptive to river systems as possible.

So far, Natel has two operational projects, in Madras, Ore. and Freedom, Maine, with several more in the pipeline; the company is planning to install two more projects this year, one in Virginia and another in Austria.

“My brother and I deeply care that that development happens in a way that supports sustainable outcomes in rivers, because rivers are our lifeblood,” says Gia, the CEO of the Alameda, California-headquartered company.

It’s All About Water

The Schneider siblings both earned engineering degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology around the turn of the 21st century. Afterwards, they took different career paths—Gia worked in finance and energy, and Abe was a mechanical engineer—but they came together in 2009 to found Natel, with their late father, with the aim of creating hydropower systems that help, rather than hurt, ecosystems. It’s an obsession that is personal for them both. Their father, a renewable energy technology inventor, taught them as children about climate change.

Growing up in Texas, Gia recalls as a teenager going on a white water rafting trip with her father to protest a large hydropower project in Canada. As teens the siblings also took regular vacations to fish at a river in Colorado. They noticed that the branch of the river with beaver dams was flourishing, while another branch where the dams were removed by a cattle company, wasn’t. Their theory, says Abe, was that the cattle company removed the dams to improve grazing because they thought the beaver dams drowned the meadows, but in reality the beaver dams created them. This realization that natural dams played a crucial role in maintaining a healthy habitat helped inspire their future approach to hydro planning.

Unlike large hydropower plants, which can have a damaging environmental footprint, Natel wanted to make turbines that would enable rivers to maintain their natural flow as much as possible to protect a healthy ecosystem. The company’s “restoration hydro” design philosophy, which incorporates the concept of biomimicry—learning from and emulating nature to create more sustainable designs—couples a fish-safe turbine with low-impact structures in strategic sites that use and mimic the natural landscape. Restoration hydro project structures might mimic beaver dams, natural log jams, or rock arches, and depending on the river and environment, it might be possible to install turbines without actually damming the river—which would dramatically change the landscape.

In doing so, the goal of restoration hydro is to help restore watershed and ecological function that may have been damaged, whether naturally or by conventional hydropower projects. On top of this, unlike traditional hydropower projects, this design supports groundwater recharge—when water seeps through the earth, replenishing aquifers—reduces flood and drought risks, and improves water quality.

“Every hydro project is also a water project, not just an energy project,” Gia says.

Tackling The Biodiversity And Climate Crisis

In order to be less hazardous to aquatic life, Natel’s fish-safe hydropower turbines have thicker, more steeply slanted blades than normal hydropower turbines. The blunt edges of the blades deflect fish, while their slope reduces the likelihood of a direct impact. Natel says its unique blade design has a greater than 99% fish survival rate.

Gia says that when thinking about tackling climate change, the biodiversity crisis can’t be overlooked. For years, researchers have been looking into how to make hydropower projects less environmentally damaging, with some using screens to prevent fish from entering dams. And in some places large hydropower projects have fallen out of favor. Other sectors of the renewable energy industry are experimenting along these lines as well: wind energy companies are working to make turbines safer for birds, for example, by painting one of the rotor blades black to make it more visible to birds, while there is increasing focus on the negative impact solar farms can have on biodiversity when land is cleared to make way for the panels.

“At the end of the day, we need to get megawatts, and clean megawatts, renewable megawatts, [which] are better than fossil fuel megawatts in the context of climate change,” she says. “But I do think that we have to prioritize biodiversity because when you zoom out to the big picture, we face not just a crisis of climate change as the earth as a whole, we also face a real crisis on biodiversity.”

Environmentally Friendly—And Cost Effective

When the siblings started Natel, they were laser focused on how to make hydropower better for rivers. At the same time, they knew that “nobody on the finance or the energy side is going to want to sacrifice efficiency or cost,” she says. “What we inserted into that equation is that we also wanted it to be fish-safe, and river-connecting, and we were like, ‘we’ll put those design criteria on par with the other constraints, and then use that to drive the engineering process.’”

Natel says the cost of generating power using its turbines is about 4-8 cents per kilowatt-hour, or $40-80 per megawatt-hour (the range in cost depends on the size of the turbine or plant; larger turbines and plants tend to result in some savings). Compare that to typical large hydropower projects in North America where, on average, the cost of new projects built over the past decade was around 8 cents per kilowatt-hour, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

Natel’s turbine also eliminates the need for fish screens, reducing both upfront and ongoing costs for things like maintenance, and the compactness of the turbines means that civil works to build plants using Natel turbines are less complex. “It’s about as efficient as any conventional hydro turbine out there, but it’s fish-safe,” says Gia.

The siblings hope that what they’re doing can help demonstrate a more sustainable approach to renewable energy—proving that companies shouldn’t have to choose between what’s good for the environment and what works economically.

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision