Frieda Fairman has been a respiratory therapist for 14 years. At Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, that typically involves working with patients on a range of breathing problems, from sleep apnea to asthma to heart attacks. Now, it means she is at the center of the hospital’s COVID-19 response.

Because Harborview is a regional trauma center that sees patients from across the Pacific Northwest, Fairman, 43, says she is used to intense situations. “We see things daily at work that most people would never see in their lifetimes. It can be overwhelming at times,” she says. “But we also take solace in the fact that this is not normal.” But after the first COVID-19 death in the U.S. happened nearby in Kirkland, Washington, Harborview started to test patients who had recently died to determine whether they may have also had the virus. “When that first test came back that showed a patient who had died previously was COVID-positive, that’s when it all of a sudden started to hit,” Fairman says.

Her hospital currently has enough mechanical ventilators and covid-19 rooms, but Fairman is already preparing for a surge in the next few weeks that could overwhelm their supplies, mirroring the situation in cities like New York, Chicago and Detroit. Fairman walked TIME through a day in her life on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

5 a.m. — Fairman wakes up early to work out or prepare food for her family before work. By the time she’s ready to leave for her 12-hour shift, her 10-year-old son, Israel, is often already up reading comics or playing with Legos. While Fairman’s gone, he logs in to attend virtual school, which has moved online since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Her husband Jamal, who is not working during the state’s stay at home order, is home to supervise.

6:30 a.m. — Her shift at Harborview Medical Center begins. She gets the report from the night shift staff and finds out her assignments—usually between four and eight patients in the Intensive Care Unit that she’ll attend to all day. Once Fairman knows which patients she’ll be treating, she gets updated on all the details of their condition: what brought the person to the hospital, their full medical history, any changes that staff saw overnight, the status of their breathing and, if they are already on a ventilator, where the machine’s settings stand. Her hospital has converted the entire neuroscience ICU to take only COVID-19 patients. They have also created three acute care COVID-19 units for patients who don’t need intensive care and have set up a triage tent outside the Emergency Department to receive people who may have the virus.

7:15 a.m. — Fairman heads to whichever unit she is working on that day. There, she looks over her patients’ charts and reviews the equipment available to her. She needs to know how many ventilators are not already being used by patients and exactly where the airway cart is in case someone else needs to be intubated, or put onto a ventilator.

8 a.m. — The first rounds of the day begin. Fairman meets each of her patients, checks to see if they’re responsive, does her initial assessment and listens to their lungs. “A huge part of what we do as respiratory therapists, aside from supporting somebody breathing, is seeing if they can actually cough and clear their airway,” Fairman says. If it looks like the condition that put a patient on a mechanical ventilator—these days often COVID-19—has stabilized, she may consider weaning that patient off the ventilator. It’s her job to adjust and monitor all of the machine’s settings, controlling how fast a patient breathes, the size of the breath they are taking, and other measures that help synchronize their body with the equipment. The ventilator needs to be minimally supporting a patient for them to qualify for weaning, she says, and all their other vital signs—oxygen levels, blood pressure, heart rate—need to be under control too.

The patient’s primary care team is also doing rounds, so as the doctors come around, Fairman stops her work to update them on her patients’ status. While this is going on, she might be pulled away to help with new patients coming in or taking others to get more tests or x-rays done.

12 p.m. — All of this carries right into second rounds. For patients who need breathing help but are not in serious enough condition that they need a ventilator, Fairman works with them on deep breathing exercises to help them cough. If they have a broken rib, for example, and are unable to cough on their own for a long period of time, that can be dangerous. “If you don’t deep breathe and cough like you’d naturally do, the smaller parts of your lungs start to collapse,” she says. In the case of COVID-19 patients, they are often short of breath, so she might give them supplemental oxygen or albuterol to help open up their lungs.

The second rounds of the day are often more calm than the morning, but a patient’s condition can change at any time. If someone worsens and needs to go on to a ventilator, the doctor will do the intubation procedure before Fairman takes over. She secures the tube, hooks it up to the machine and ensures all the settings are appropriate. “The ventilator is a very technical piece of equipment,” she says.

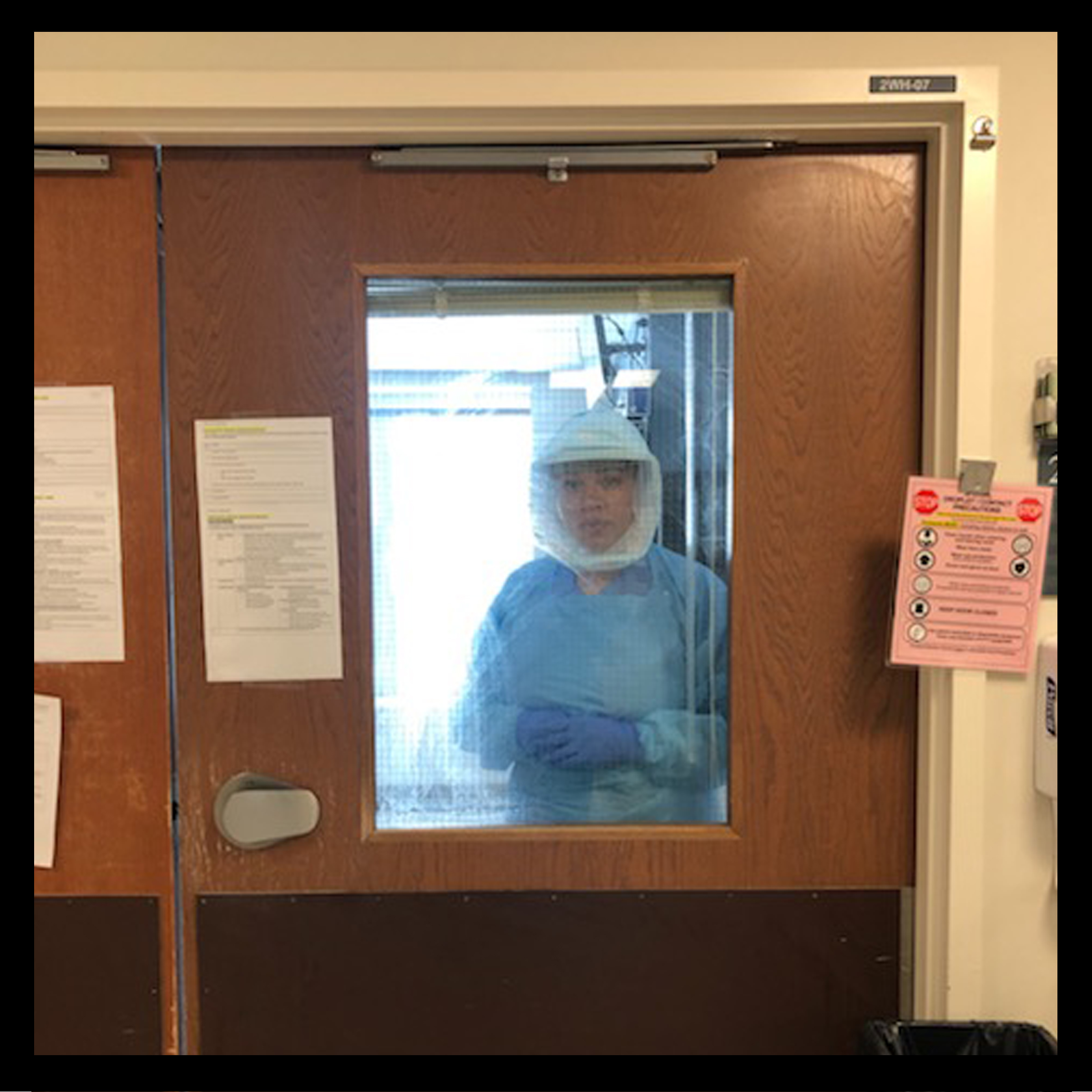

1:30 p.m. — Fairman quickly grabs lunch. She’s always careful about infection control—every time she leaves a patient’s room, she stands in a “hot box” space taped on the floor and a colleague watches her remove her personal protective equipment to ensure everything is done properly. “By the time I go to lunch, I probably wash my hands 40 times between the hand washing and hand sanitizer,” she says. Fairman typically tries to bring a sandwich or something healthy like fish, especially now that ordering delivery is harder since no visitors are allowed in the hospital.

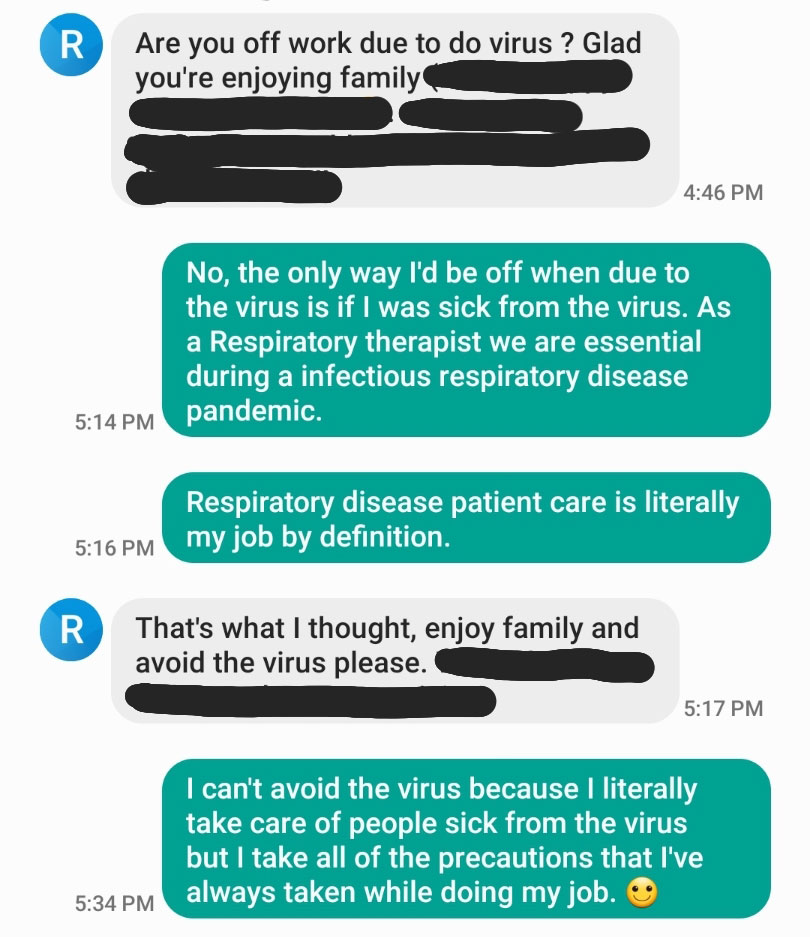

2 p.m. — During the day, Fairman says she tries to text or call her husband and kids to keep them up-to-date. “I just try to encourage my family not to be anxious about me going to work and bringing anything home to them,” she says. “I’ve been a respiratory therapist for 14 years and so respiratory infection has been a part of my life for this entire amount of time.” Since COVID-19 started, her hospital has chosen to re-use masks and other personal protective equipment, but they haven’t seen huge shortages yet. “I’m going to take every necessary safeguard I can,” Fairman says.

3 p.m. — Then it’s back for final rounds. This is the “tidy up round,” Fairman says. If a patient’s condition has improved, Fairman might get to see them move out of the ICU, but if their breathing has worsened, they might need to be intubated. With the number of COVID-19 patients increasing by the day, Fairman says she now sees more patients going on ventilators than coming off.

6:30 p.m. — Fairman logs everything that has happened during the day in each patient’s chart and prepares to give her evening report by 6:30 p.m. She writes about how the patient looks, how their lungs and other vital signs are doing, how they’re tolerating the ventilator or responding to other breathing treatments. When COVID-19 was not a factor, she could talk to patients’ families or other visitors about their conditions, but now that no visitors can be in the hospital, it’s especially important to keep track of every detail so families can be updated when they are available.

“Last weekend, one of my COVID patients, she was intubated on the breathing tube and we had to have her really heavily sedated because she wasn’t tolerating the breathing machine very well. And so we had her family on FaceTime. There was an iPad in there. We had it in a plastic bag and the family was able to call in and I just literally had it propped up so that they can just talk to her even though she wasn’t awake,” Fairman explains. “That’s not always the case.”

7 p.m. — After giving her final report to the night shift staff, Fairman changes out of her scrubs and back into clean clothes as an extra precaution before leaving the hospital.

7:30 p.m. — When she arrives home, Fairman disinfects. “As soon as I walk in the door, I take my shoes off, put them in a certain area. Literally go right upstairs, take everything off and jump in the shower. So then usually my husband and my 10-year-old will go around and wipe door handles and all that stuff,” she says. She has told her son not to touch her until she’s taken a shower. “My son might want to come up to me and give me a hug, but he’s been better about it in the past couple of weeks. I’m like hold on, I’m not clean,” she says.

8 p.m. — Israel eats dinner before his mom gets home most nights, but then Fairman says the family tries to play card games or talk about their days to keep up a routine.

9 p.m. — She and her husband put their son to bed. Before the pandemic, Fairman also taught a clinical practicum at Seattle Central College each week, but that has been canceled since mid-March. The shelter in place order has meant the family actually has more time to spend together these days, which is a gift when everything else going on is so intense. She’s used to dealing with tough situations at work, but COVID-19 feels different. “Now when we look outside our bubble and it’s everywhere is what makes it even harder,” Fairman says. “There’s no way for us to rectify that this is not normal. It’s affecting everybody.”

Even when she leaves work now, it’s hard to escape the constant information about COVID-19. Fairman says she deleted her Facebook account recently because she needed to get away from the overwhelming discussion. “There’s no way to get away from it,” she says. “That’s how it feels. You’re just going to keep getting inundated with it at work and in your community.”

Still, she says she is not an anxious person, and maintaining her schedule has helped keep her steady in this uncertain time. In addition to the extra hours with her 10-year-old and husband, she makes a point of checking in with her older son, 22, and daughter, 18, who don’t live at home.

12 a.m. — Fairman, who is also a bodybuilder and used to compete in national figure competitions, says she knows she should go to bed early most nights so she can get up early to lift weights and do cardio exercises. But sometimes she stays up late just to chat or listen to music with her husband.

Their extended family and friends do worry about her. But on a recent group chat with friends, she reassured them: “Before this pandemic I was a respiratory therapist, and I’m still going to be a respiratory therapist through this pandemic and after this pandemic.”

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision