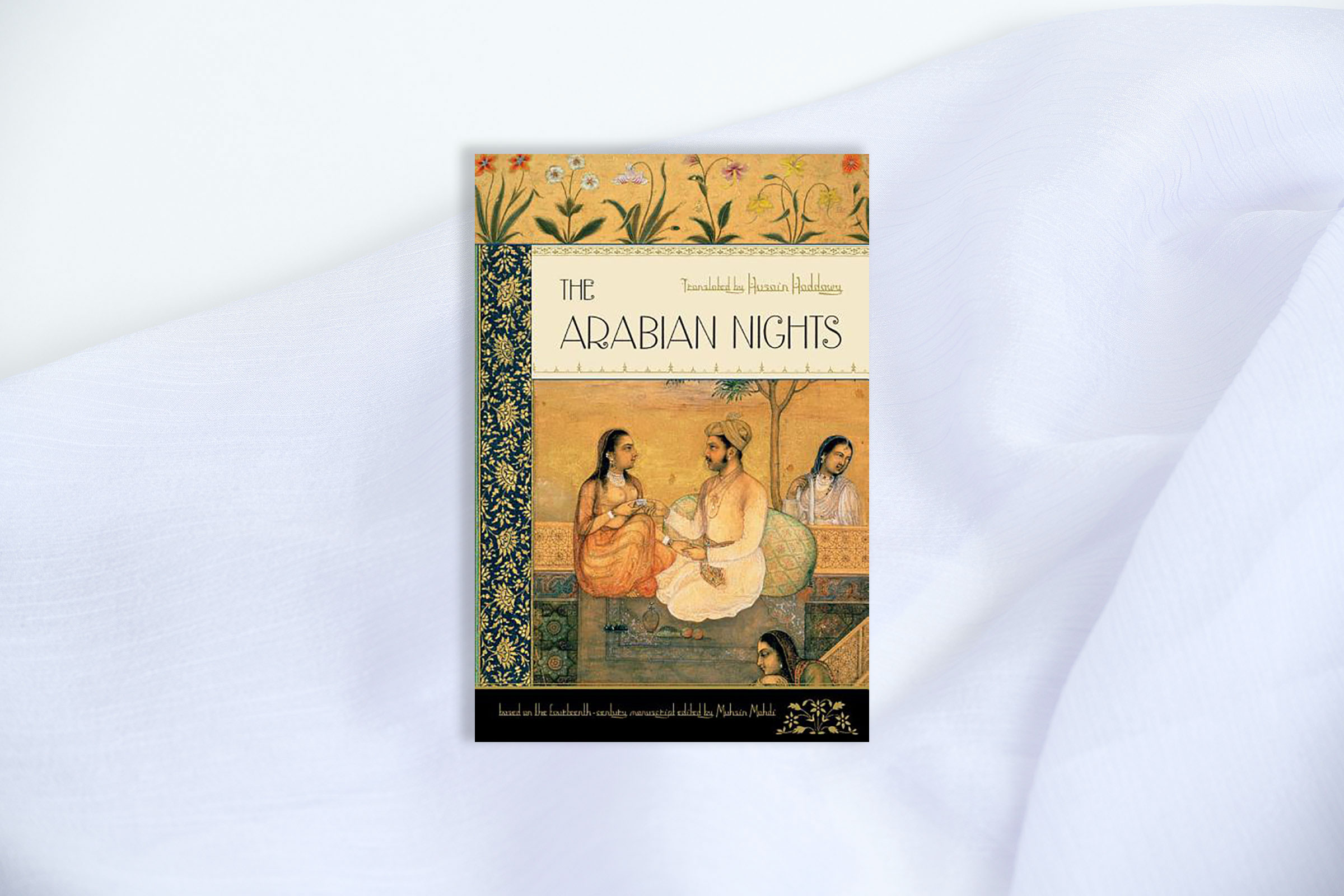

Nearly everyone is familiar with this collection of folktales, also known as One Thousand and One Nights, and its infamous framing device: Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, is set to be married and then killed by the king; she forestalls this destiny by convincing the king to hear a story, which she then draws out for 1,001 nights by ending each evening on a cliffhanger. (In other words, Scheherazade invented narrative television.) It’s hard to ignore that, from the start, this book of short stories is deeply misogynistic; the problematic gender dynamics of its time are pervasive and often stomach churning. And it’s rife with racism toward dark-skinned Africans and casual discrimination of Jews. It’s also impossible to ignore the tremendous influence on storytelling these tales have had, far beyond the Islamic Golden Age in which they were initially compiled—the earliest known printed page dates back to the 9th century. There are stories within stories (within stories, sometimes); there are unreliable narrators; there is foreshadowing; there are plot twists. There are tales of horror, crime, sci-fi and, of course, fantasy. (There is not, as pop culture has led us to believe, a tale of Aladdin, nor of Ali Baba and the thieves.) Without The Arabian Nights—and its genies, sea monsters, automata with life breathed into them, demons commingling with humans and more—it’s hard to imagine certain elements of works by H.P. Lovecraft, H.G. Wells, Jorge Louis Borges, A.S. Byatt, Edgar Allan Poe and the entire comic book industry, just to name a few. While there have been many editions and translations of The Arabian Nights, Mushin Mahdi’s 1984 Arabic-language edition and Husain Haddawy’s corresponding 1990 English translation are among the most celebrated. —Elijah Wolfson

Buy Now: The Arabian Nights on Bookshop | Amazon

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time