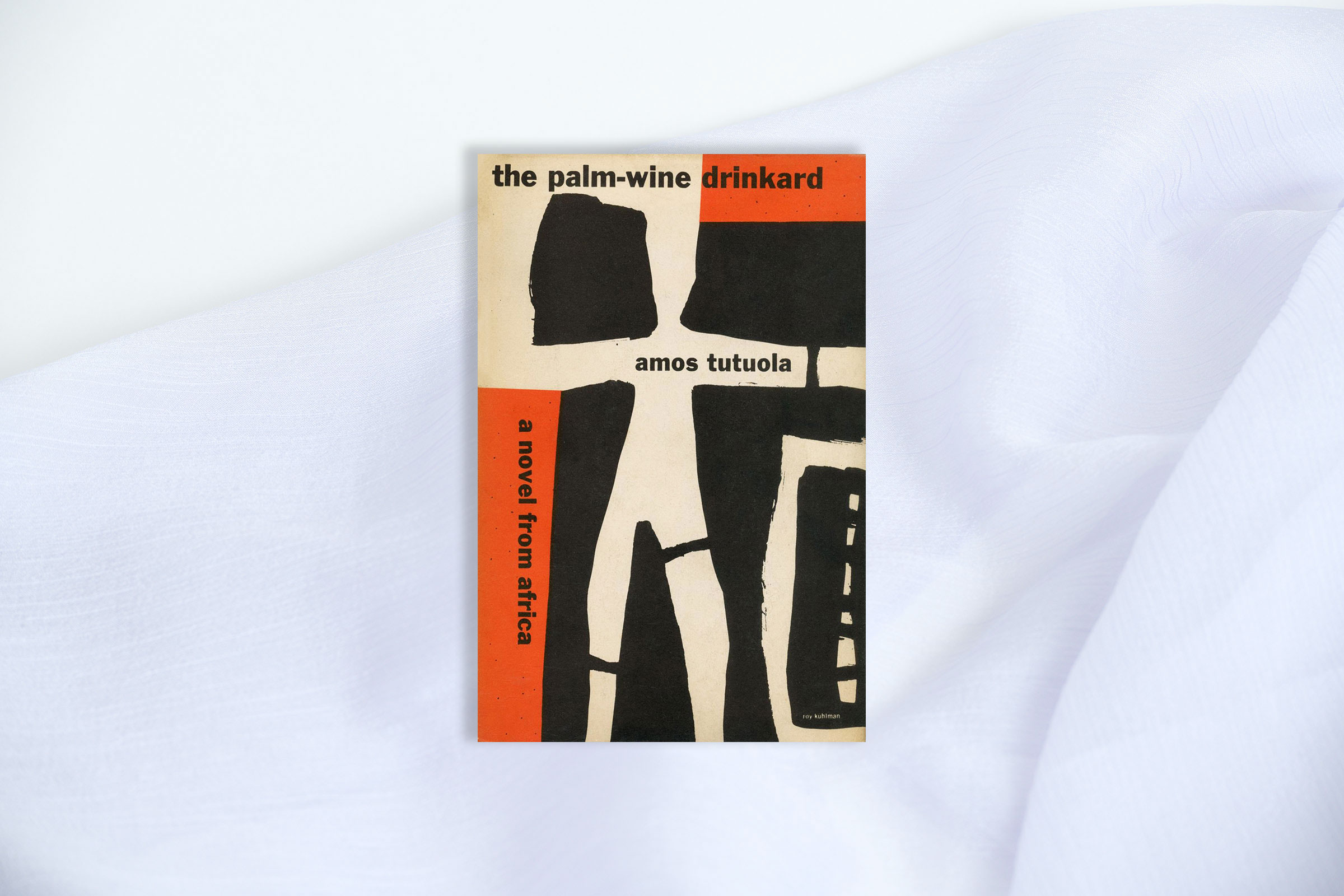

In 1950, Amos Tutuola, a 30-year-old Nigerian, read a magazine and decided he could write too. He drafted what would become The Palm-Wine Drinkard, and sent it as a response to a “manuscripts wanted” ad put out by Lutheran World Press, a Christian publisher. A year later, Faber & Faber, one of the preeminent publishers of English literature, sent him a letter inquiring about publishing it. Soon after, it appeared in print across the U.K. and the U.S. At the time, it was unlike anything English-language readers had ever seen; even today, it’s bracingly original in its voice and ideas. The story’s protagonist and narrator is an alcoholic with God-like thirst and resilience: He drinks 225 kegs of palm wine a day, and that is all he does. The inciting incident of the novel is that his “tapster” dies, and there is no longer anyone to get him all the palm wine he desires. So, the narrator sets off to seek the Deads’ Town, where he believes he can find his tapster, now in his post-life form, and bring him back to his village so he can return to his life of drinking transcendent amounts of booze. Along the way is a sort of picaresque of the grotesque, where the narrator encounters monsters, (mostly malicious) magical beings and all sorts of incarnations of death and destruction. Tutuola, writing at a moment when the Yoruba culture he was born into was colliding with that of British Colonialism and Christian proselytism, weaves in aspects of the new West African modernity with Yoruba myth and oral storytelling so seamlessly you could blink and miss it. And the language, too, feels unique to the moment: Tutuola uses the Colonial British he learned in Anglican school to create a more propulsive and energetic version of English to tell the stories of Western Africa. —Elijah Wolfson

Buy Now: The Palm-Wine Drinkard on Bookshop | Amazon

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness