With China’s one-child policy ending on Thursday after more than three decades, looking back to when—and why—the strict policy was first implemented shows us how China’s demographics have shifted in critical ways.

In the 1970s, many countries around the world were worried about population growth, but China, with its combination of a particularly large population and a powerful government, took an extreme approach to the problem. The country initially ran a successful birth control campaign under the slogan “Late, Long and Few,” which cut population growth by half between 1970 and 1976. But, as the decade came to an end, that drop leveled off and the nation was still facing food shortages and fear of a repeat of the devastating famine that killed some 30 million people by 1962.

In 1979, the Chinese government introduced a policy requiring couples from China’s ethnic Han majority to limit themselves to one child. The official start of implementation came in 1980, with an open letter issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The letter outlined the population pressure on the country and set out a goal of curbing population growth, bringing the nation’s total below 1.2 billion at the end of the 20th century. As reports from the time noted, the nation’s 38 million Communist Party members were told to use “patient and painstaking persuasion” to teach the rest of the population how important it was to practice family planning.

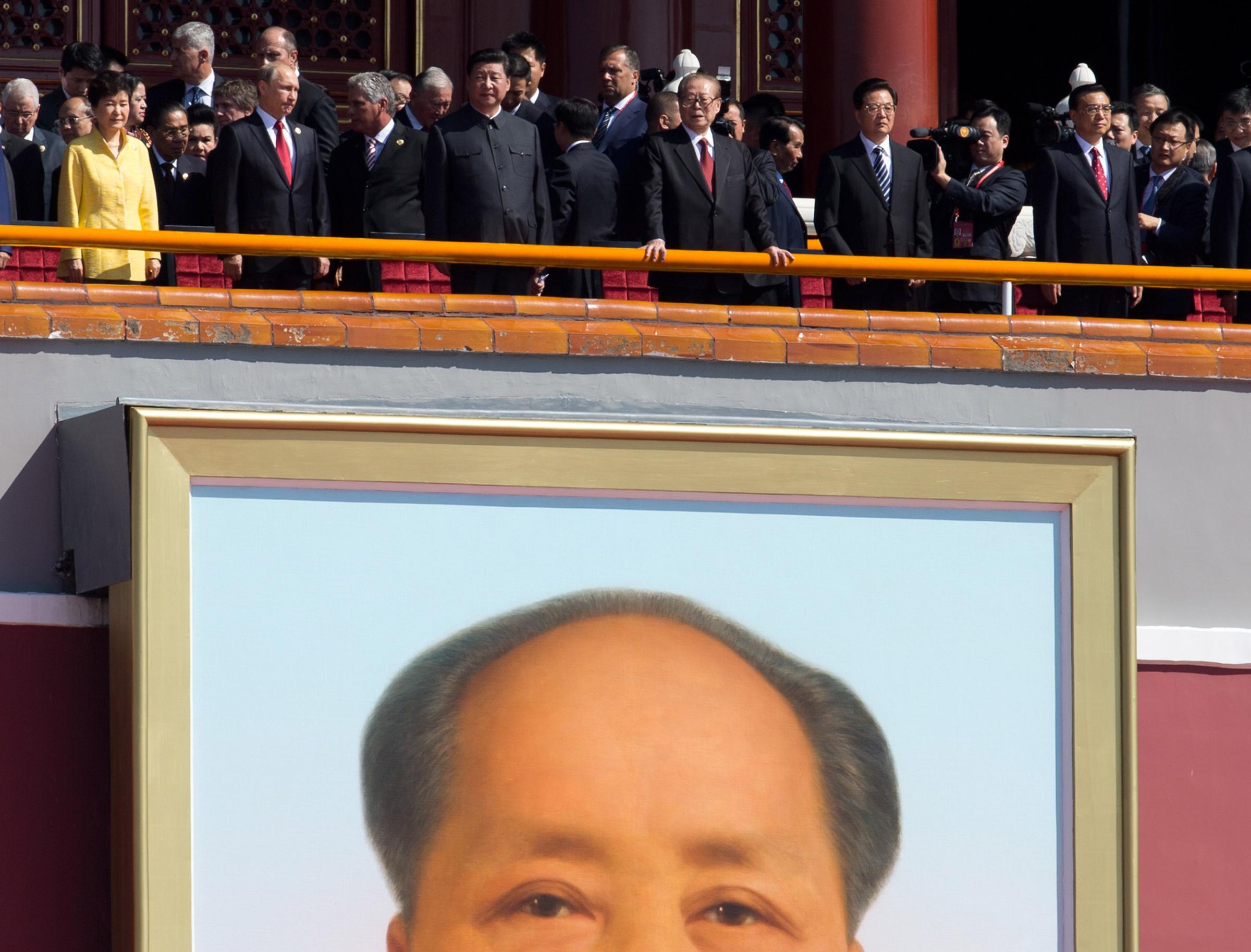

See the Official Flag Raising for China’s National Day

To enforce the law, the Chinese government could fine couples for having another child without a permit. The law also incentivized single-child homes by offering longer maternity leave and other benefits to such families. Compliance with the law was seen as a revolutionary good for society; couples who abided by the mandate were awarded a “Certificate of Honor for Single-Child Parents.”

The policy was relaxed slightly in the mid-1980s, with the government allowing second children for some families in rural areas or offering exceptions for households in which both parents were themselves only children.

For a while, the unprecedented policy could be considered a success, at least in terms of population goals. As TIME’s Hannah Beech reported in 2013:

The family-planning program, coupled with market reforms launched around the same time, is credited with catalyzing China’s modern transformation. With fewer bellies to feed, the government turned a hand-to-mouth society into the world’s second largest economy. Although many families, especially those in the countryside, are exempted from the one-child maximum, Chinese women bear, on average, about 1.5 children, compared with about 6 in the late 1960s.

But still, the law has been controversial since its inception, as it contributed to concerns over forced abortions and sterilization, and a gender imbalance resulting from female infanticide.

Now as China faces an aging and shrinking population rather than an exploding one, the government has decided to end the controversial policy.

Read TIME’s take on the one-child policy’s effects from 1987, here in the TIME Vault: Bringing Up Baby, One by One

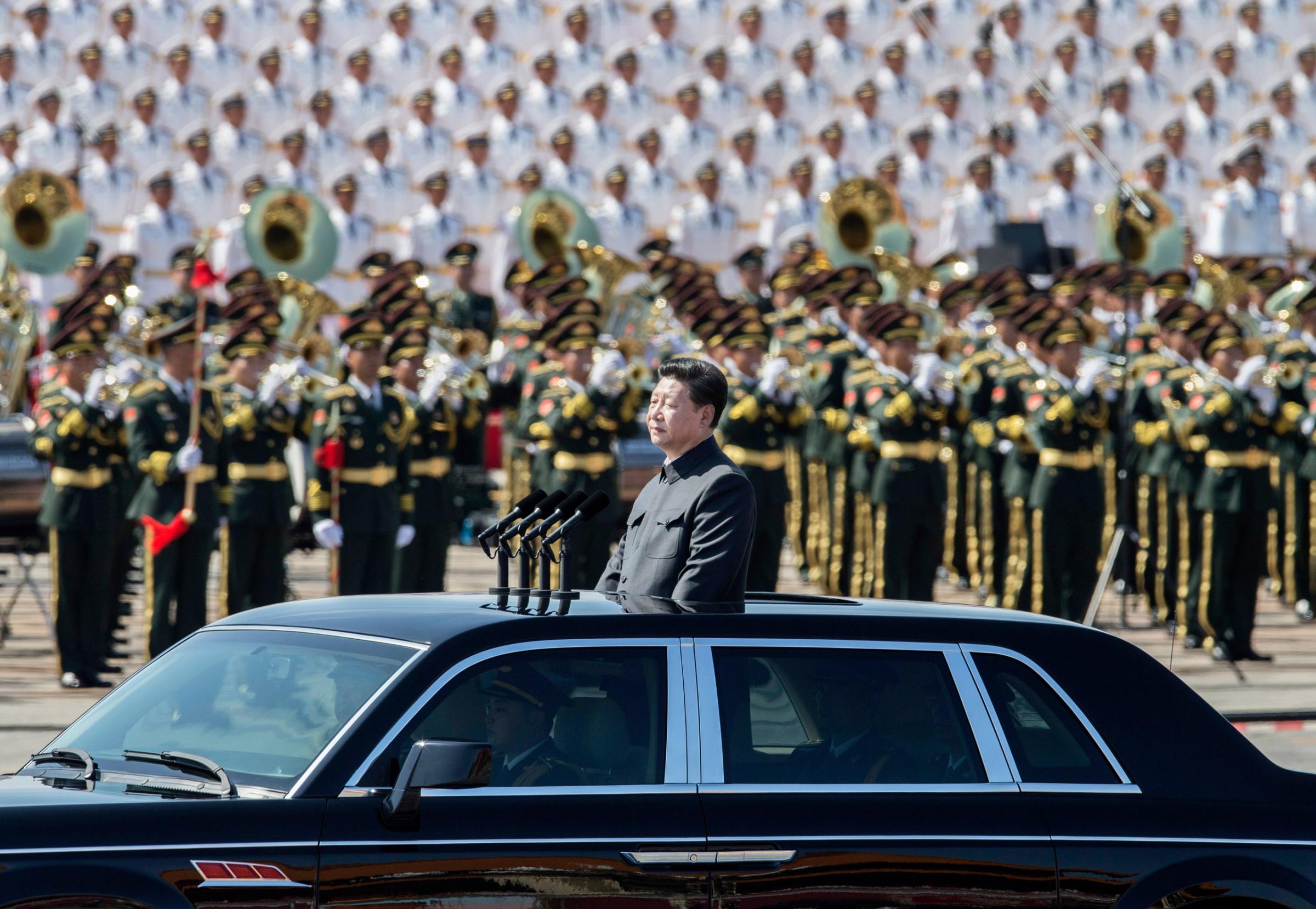

See China's Epic Parade Commemorating the End of World War II

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Tessa Berenson Rogers at tessa.Rogers@time.com