Legos. Jigsaw puzzles. Knitting. Playing catch against an empty wall.

There’s a certain corner of the internet that abounds with advice from support-center employees about how to stay entertained in an often rotely repetitive job. On the Reddit forum “Tales from Call Centers,” workers describe more elaborate tactics: doing Google deep dives on customers, taking notes on calls to assemble into a novel, mentally arguing both sides of a debate.

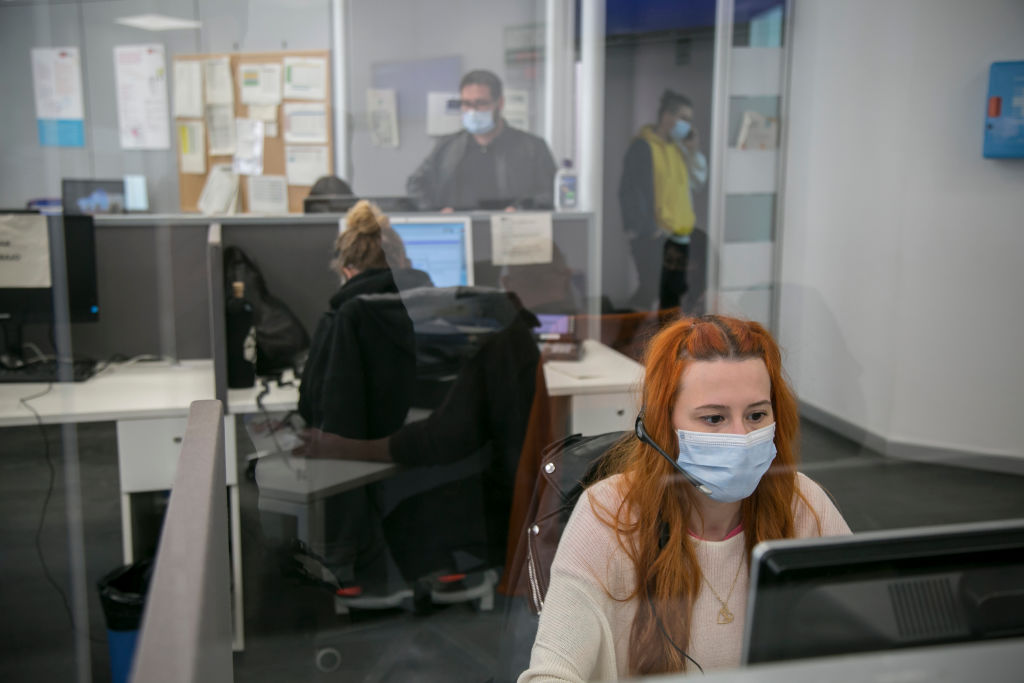

One recent survey from the pay-benchmarking site Emolument identified support functions as one of the top three most boring job categories, with 71% of employees in that group describing themselves as bored at work—a designation that’s supported by study after study examining boredom in front-line customer-experience workers. In call centers, which have a notoriously high attrition rate, many industry experts point to boredom—the monotony of fielding call after call, the lack of autonomy in adhering to preset scripts—as a key driver of employee burnout.

Researchers call it “boreout”: the sense of depletion that comes from being underwhelmed on a prolonged basis at work, characterized by many of the same symptoms that accompany more typical burnout, including disconnection and exhaustion.

And at a time when more than half of US workers report feeling at least somewhat burned out, the problem of boreout takes on its own added urgency. Remote work, for all its upsides, has made many of the issues common to call centers endemic among knowledge workers more broadly. More people than ever are doing the same thing in the same place, day in and day out, without the sense of variety that a change of environment or in-person collaboration can bring.

“Most burnout is actually the result of being underwhelmed—not that it’s too stressful, but that there’s no stress at all. There’s just nothing,” says social psychologist Ayelet Fishbach, a professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and the author of Get It Done: Surprising Lessons from the Science of Motivation.

“There’s this u-function of motivation, that you’re motivated when you’re optimally engaged,” Fishbach explains. The upside-down ‘u’ shape, known as the Yerkes-Dodson law, plots out a Goldilocks state for engagement, when neither stress nor disinterest is dragging it down.

In settings like call centers, where the risk of boreout is high and the nature of the work itself often leaves little room for flexibility, it becomes all the more vital for employers to understand the psychological factors that pull employees toward the bored end of the curve. We talked to Fishbach about creating new challenges, when rewards aren’t the answer, and small changes to work setups that have outsize impact in preventing boreout. Here are excerpts from our discussion, edited lightly for length and clarity:

Talking about boredom and lack of motivation at work feels like a little bit of a chicken-and-egg question. Which one typically comes first? How do those two things play off each other?

From the beginning of organizational-behavior studies, people have looked at how to create a work environment that’s not too repetitive. A case I teach in my classes is when General Motors partnered with Toyota to create a joint venture back in the ‘80s, when Toyota brought to the table the idea that people’s jobs building cars should not be boring. General Motors had a hundred job descriptions, which meant every person was basically putting a single screw in a car. Toyota shifted to a team of five people building a car, with the sole purpose of making it more interesting.

It was an interesting case of teaching American managers that people are people, and they’re not good at repeating the same behavior again and again. All that is to say that people are variety-seekers and sensation-seekers. We truly struggle with doing the same thing again and again, and the more minute that activity, the more repetitive, the harder it is to stay focused. The likelier it is that our minds will wander, and the more likely it is that people will make mistakes and eventually burn out.

How can burnout be prevented in settings where there are some constraints around changing the nature of the work itself—when it may be more repetitive or there’s not as much variety in jobs to be done?

The challenge is to bring intrinsic motivation to it, and the common practice there is to do something with other people. We’re social animals. To bring intrinsic motivation to this boring job, do it with another person.

My grandmother used to work in a factory putting covers on plastic tubes. It’s as boring as it sounds. You do it for hours: You take the cover, you take the tube and connect them. But there were a bunch of ladies sitting together and having a conversation for hours, discussing every trash TV show that they watched. And she was quite happy with that.

So bring something external to the job, but do it while people do the job. We also know that many people like to do their work while listening to music, for another example. It’s the idea that as you do your work, there’s something fun going on. There’s something interesting and sufficiently engaging without being too distracting.

It’s not, ‘Do this boring job and by the end of the month I’ll send you some award.’ Anything that’s long-term is less effective. People are motivated to do the task for the long-term benefit, but they don’t feel as intrinsically motivated as they do it. It’s like finding the interesting workout instead of the boring one, or bringing music and books to the gym. It’s much more effective than thinking about the long-term benefits of doing the workout. Not that compensation is not important. Obviously it’s important. It’s not enough.

To what extent is lack of challenge a separate component of burnout from lack of variety? Is there an optimal level of challenge to ward it off?

In general, what we find in terms of achievement motivation is that you need the challenge to be at a medium level. If you present people with a really easy task, you see no change in heart rate. If you present an impossible task, you see no change in heart rate. But in between, you have the task where people energize themselves.

For the work to be interesting, I need to be thinking it’s unclear whether I’ll be able to do a good job. There needs to be some question whether it’s even possible to do a good job. It’s not a huge uncertainty—hopefully when a surgeon is operating on a patient, they have pretty good confidence they can do it right—but it’s not 100% guaranteed. You need to be concentrating. You need to try. It’s not just going to happen by itself.

Are there any best practices employers can use to figure out what a medium-level challenge looks like for their employees?

There’s no simple recipe. What might be challenging and interesting for me might be too simple for you and might be overwhelming for someone else. You need to remember that your employees are not machines—the machine can do the same bad action over and over again and never get tired, but people need to have some cycling between different tasks that they do.

And you need to keep track of who did what, so that people do different things in some rotation. What’s motivating for a person their first week on the job is different from what motivates them six months into doing the job. Now they have expertise and experience, and they need to do something harder.

You also need people to understand why they do what they do. If you’re building a car, you should understand how what you do makes a car. If you’re doing customer service, dealing with calls, you need to understand how that fits with the agenda for the store or the service provider. Why am I going through this script? What am I trying to get?

Once someone is burned out from underwhelm, can that be undone?

Like any other problem, it’s easier to prevent than to fix. But the strategies will be the same. You’ll try to change something about the context in which people do their job, so you’ll switch roles or get them to interact more with other employees. Create social context. Introduce challenges.

And gamify the workplace. For more mundane jobs, one of the classical studies had people just copy text. And what the researchers found is that people were switching from their right hand to their left hand, from red text to blue text. They were doing competitions with themselves over how much text they could copy in a minute. Basically introducing challenge to something that was awfully boring. You can be in competition with yourself and make it interesting.

I hesitate to say that you should do a competition that will turn people against each other. When you talk about people in customer service, they already have to deal with the consumers and the bosses, and now if they also have to be in competition with fellow employees, that’s kind of the worst advice. We can make it more like a game without creating enemies. You want it to be so one of the main reasons to go to work is to have that social network. Do not mess up the social network that people created.