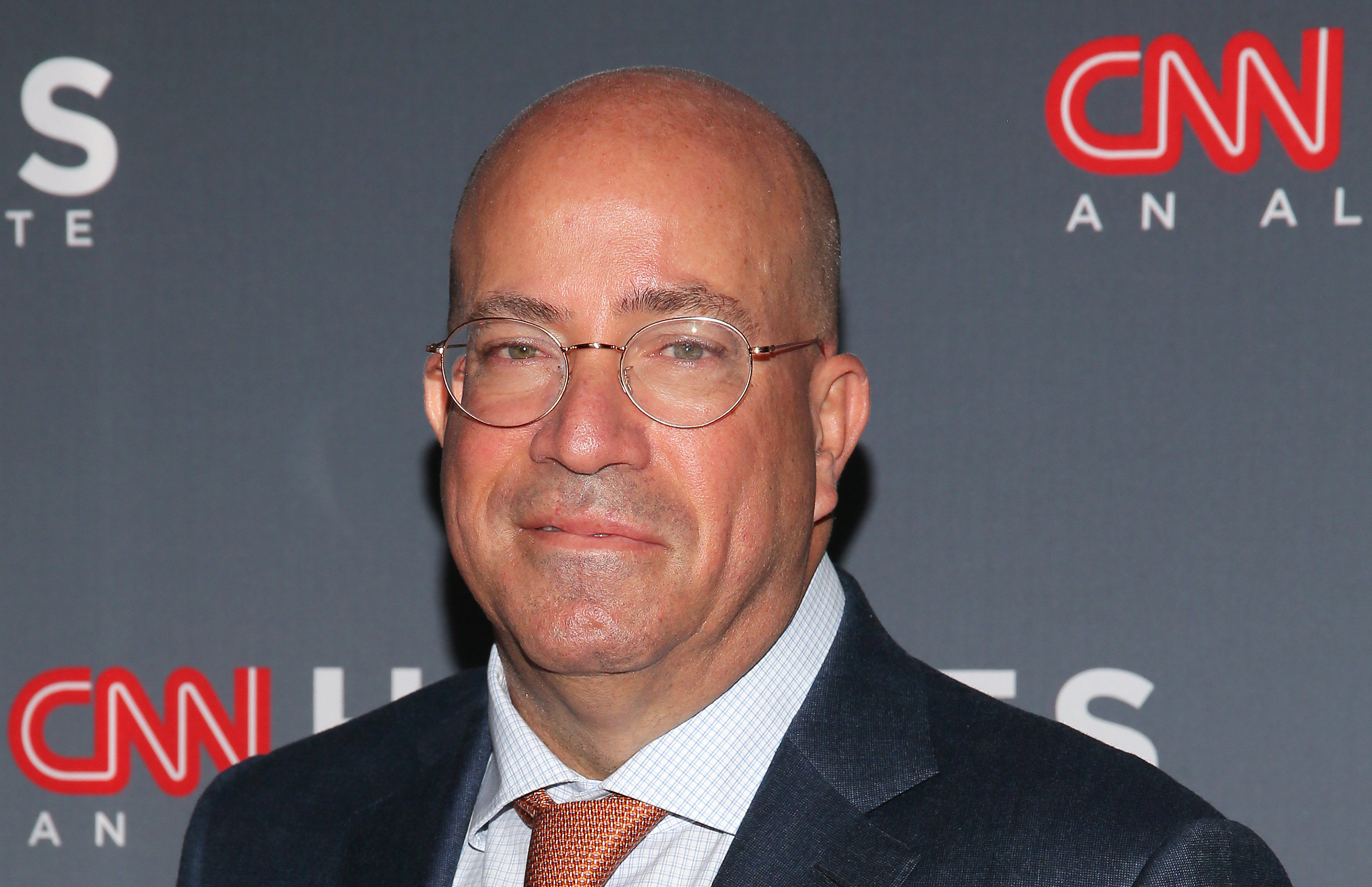

A week ago, Jeff Zucker, CNN’s president and someone I worked with for 4 ½ years, resigned after admitting to a relationship with his top deputy and stirred up a media firestorm.

The dissection of ethics and timelines, conspiracy and hagiography, shows no sign of letting up. The left and right found rare unity in saying good riddance. Yet inside CNN, which Zucker led for nine years, staffers are bereft; Don Lemon and Fareed Zakaria both shared statements of gratitude on their shows.

Why?

I know too little to indict or defend Zucker on what transpired at the company I left 14 months ago, but I do know that the man was a master of messaging and of management. Zucker made his name as a big boss presiding over “Today” and then, later, NBC Universal, but I’m convinced the best show he ever produced was one almost no one saw: his morning meeting, which took place every weekday at 9 am EST.

Yes, a meeting. Meetings have increased 70% since before the pandemic. And they are largely despised; one survey of managers reported 83% of meetings were unproductive. Another rated meetings the “number-one office productivity killer.”

I have worked in at least a dozen newsrooms that have some version of that morning news huddle. None matched the energy of what I saw at CNN, balancing the delivery of information, priorities, vulnerability, openness, and a willingness to change with the story, or with the times.

What made Jeff Zucker’s meetings so special?

Authenticity, ironically, requires great orchestration.

Zucker himself produced the meeting as though it was a show. He arrived having read across all corners of the internet. Sometimes he had papers in hand, while other times he recited tidbits from memory, from a viral video of a baby hearing for the first time to the case for death by age 75.

And like any show, he would first warm up his audience. In the few minutes before 9 am, he’d often banter with those of us trickling in: “What’s the most important news story of the day?” One day, his eyes lit up when I said the US reopening the case of the death of Emmett Till. I had the right answer.

He would script the meetings as well. “That point you made yesterday?” he once said to me. “Say that. It’s really smart.”

Once a week, there might be some announcements of awards, staff moves, new initiatives. With about 4,000 employees around the world, these were often the only common touchpoint in the behemoth organization. Anyone who has worked for a big company knows how hard it is to push change; by aligning people in this daily scrum, it felt like the screws actually turned, albeit slowly.

The meeting was open to everyone.

“Good morning!” he’d start. Then he’d dive in with the story or priority of the day and have the team running coverage detail their plans. Built into the roughly 45-minute meeting was plenty of opportunity for others to jump in with thoughts.

The meeting served as a forum to air story ideas, opinions, even grievances. So much of working in corporate America (and CNN was no exception) is the surreptitious jockeying to get closer to power. That manifests in promotions and resources, but also less-talked-about flexes like flying first class or sharing photos of partying with colleagues on Instagram. The 9 am meeting, though, gave an intern the same chance to weigh in as an executive producer. It was rare—but it was possible.

If someone new spoke up, it often changed the energy of the rooms (New York, Atlanta, and Washington, DC were always on videoconference, but people called in from everywhere around the world).

We worked to make his meetings more inclusive.

Granted, these meetings suffered from the common plight of hearing from the same half-dozen white guys over and over. Zucker took that criticism to heart and asked a few of us what he could do to foster more participation.

I worked on the digital side and was among a tiny number of women of color in CNN executive ranks. As I’ve often written, that comes with double expectations from management and from your own communities. Many times during the morning meetings, there would be side chats, text messages, Slack channels exploding from staff irate over the direction our news agenda was heading. “Why don’t you say something?” I often wrote to the dissenters.

Sometimes, I’d summarize the points and share them publicly, hoping I was getting it right. During my time at CNN, my team grew in scope, numbers, and diversity; one of the challenges was reflecting the diversity within viewpoints. Some people thought we shouldn’t repeatedly run videos of police fatally shooting Black men; others felt we needed to show the truth. Some people thought we should call president Trump a racist; others thought it would open us up to more attacks of being biased.

The most uncomfortable moments of my career unfolded in those meetings; the backdrop of my time at CNN was reckoning with Trump himself. And yet, when you feel your role in a newsroom is to represent people who might not be at the table, you swallow your pride and just do it. In my first year, I found myself leaving that meeting red-faced and self-conscious so many times, then calling or texting friends saying I had just said something stupid again or that nobody seemed to understand me. One friend gave me good advice: “You have exactly seven minutes to obsess over this. Then you gotta let it go.”

I tried her tactic. I also found myself feeling affirmed when Zucker would not only approve of my ideas but would be effusive in his public praise. “I think we should do every single one of the stories Mitra just rattled off,” he once said, as I implored us to cover education more closely.

He was vulnerable.

Zucker, a two-time cancer survivor who has Bell’s palsy and underwent surgery for a heart condition, was fairly open about his own ailments. On the morning of June 8, 2018, he choked back tears as he told the staff about the death of Anthony Bourdain and implored people to seek help if they ever needed it. We knew nothing mattered more than our own health and safety, and these meetings often underscored this basic but important pillar.

Was his vulnerability part of the old-school style of management, where you operate on instincts and relationships? Was it honed and fashioned after stints in other top media jobs where he also fell from grace? Was he orchestrating a feeling of flatter hierarchy than is actually possible in a matrix organization dependent on assembly-line-style production? I think it’s a bit of all of that.

For all of the polarizing language surrounding Zucker now, his legacy and management style and decisions are enormously complicated. Those morning news meetings often reflected that nuance, in ways that the finished product–the economics of linear cable television, the loud roundtables debating an issue, the anchor essay styled as an outraged monologue–cannot. That, in some ways, was the benefit of a free-for-all, day-in, day-out interaction with the president of the company. It was aspirational and open to many sides, even as the rest of the country felt firmly split into two.

When Covid shut us down in March 2020, we shifted to audio meetings, but they remained the connective tissue of a network and workplace now even more distributed and sprawling. Their rhythm had been established pre-pandemic so some semblance of normalcy and routine prevailed, anchored our day and set an intention for the work, despite all the chaos and uncertainty.

As president, Zucker possessed a superpower. The rank-and-file always know who their leader is; the opposite is not always true. A former colleague texted last week: “He made us feel seen.”

Zucker shocked CNN staffers when he announced his resignation last Wednesday. But there was one early sign of the storm to come: A few days prior, he had stopped running the morning meetings.