As India awaits the final results of its marathon elections, officials are getting ready to breathe a collective sigh of relief that the world’s largest democratic exercise is nearly over. Polling, which started on April 7, took place on nine separate days over five weeks, and ended on May 12. Voter turnout hit a record high of over 66%, compared to 58% in the last national polls in 2009, with final results expected on May 16. “Despite the heat of the Indian summer, we have had a historic all-time high voter turnout, which was a great achievement,” says Akshay Rout, director general of India’s Election Commission.

This was not India’s longest election cycle — 2009 was a few days longer, says Rout — but it wasn’t exactly speedy. So why does it take so long for India to vote? The short of it is this: India’s big. According to the government, there were some 814 million eligible voters in this election — more than the combined populations of the entire European Union or North America. Those voters speak dozens of languages and live in some of the world’s most chaotic urban spaces and some of its most isolated villages. “This is not only the biggest election in the world, it’s the largest human management project in the world,” says S.Y. Quraishi, former chief election commissioner and author of An Undocumented Wonder — The Making of the Great Indian Election. “It’s a very plural society, and we have to make sure nobody is left out.”

To do that, the government deployed some 11 million employees, including security forces and government workers, to help carry out the polls at over 900,000 stations smattered around the country. Nearly two million electronic voting machines were dispatched to help the government keep its pledge that no one should have to travel more than a mile or so to vote. A polling station was set up in Gujarat for a single man who lives in a forest there, complete with staff and its own voting machine. The availability of central and state police to keep voters and workers safe dictates the length of the vote, as does moving them and the necessary equipment around the nation. The days on which voting takes place also have to take into consideration local festivals and school and farming schedules.

Such a prolonged process is not without disadvantages. This cycle, voters and observers were critical about the tenor of the political debate, with top politicians taking increasingly low pot shots at each other as campaigning intensified over the five-week period. More worrying, perhaps, is the likelihood of voters at the end of the cycle being influenced by media reports of the vote’s progress. Opinion polls and exit polls during the voting period are not permitted, but India’s robust domestic 24-7 news cycle would have been hard for millions to avoid. One could certainly argue, for instance, that the opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) may have benefited from a sense of growing popularity of its prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi conveyed by the media during the five-week vote, potentially giving the party an advantage that a one-day poll would not have offered.

But paramount in the process is security, says Quraishi, both to protect voters and election workers in insecure and remote areas, and to ensure that polling booths aren’t commandeered and rigged in favor of a certain politician. Despite precautions, there have been several incidents of election-related violence this year, including a landmine blast that killed seven police officers in a Maoist area of Maharashtra one day before the final May 12 vote. There were also incidents of deadly election-related violence in Kashmir, Jharkhand and Assam. Still, Indian elections used to be a much bloodier affair, Quraishi says. Voting may be long but it is, by and large, peaceful. “Anything that upsets a free and fair election is upsetting to us,” he says. “But what’s the alternative? Loss of life isn’t worth it.”

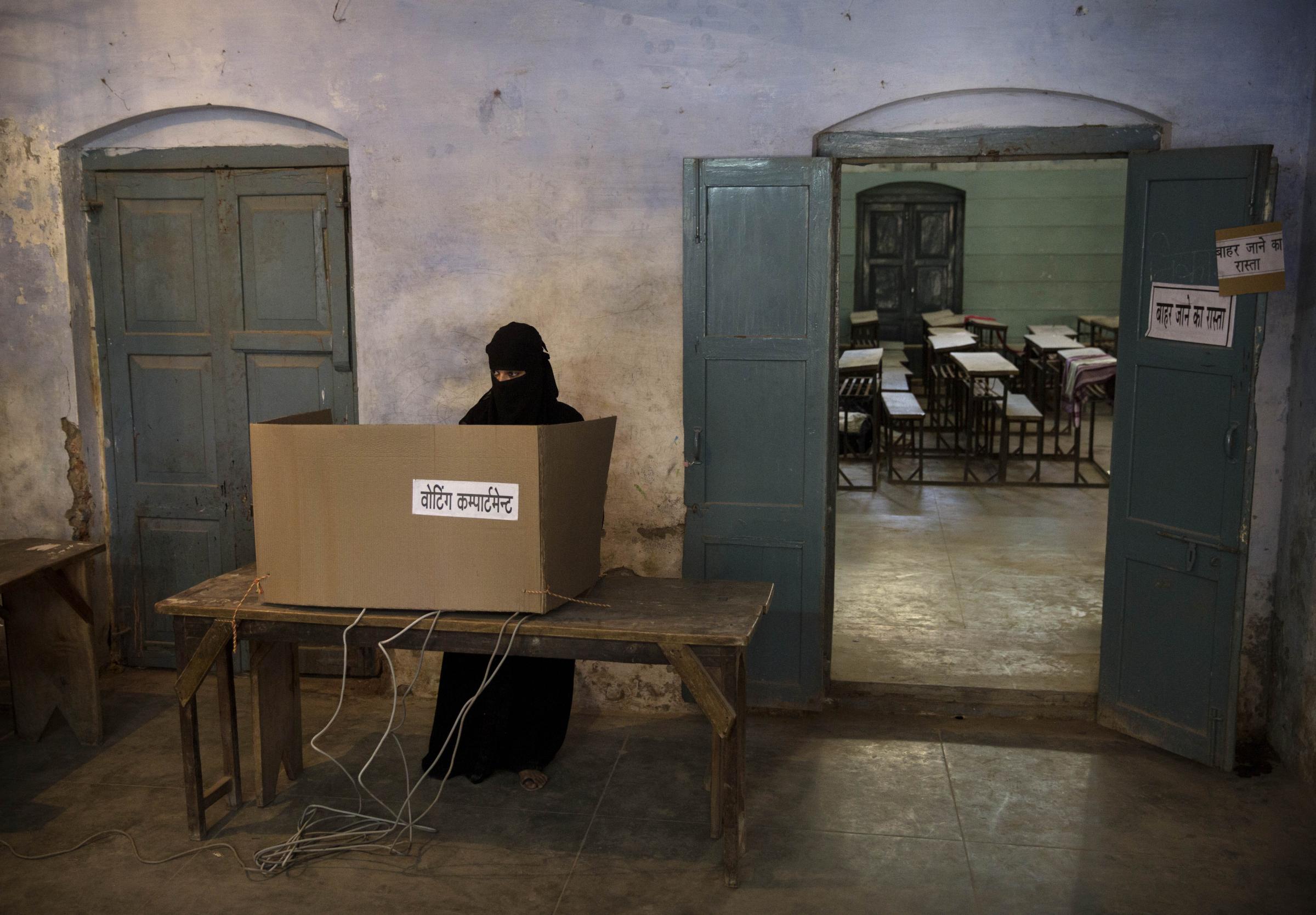

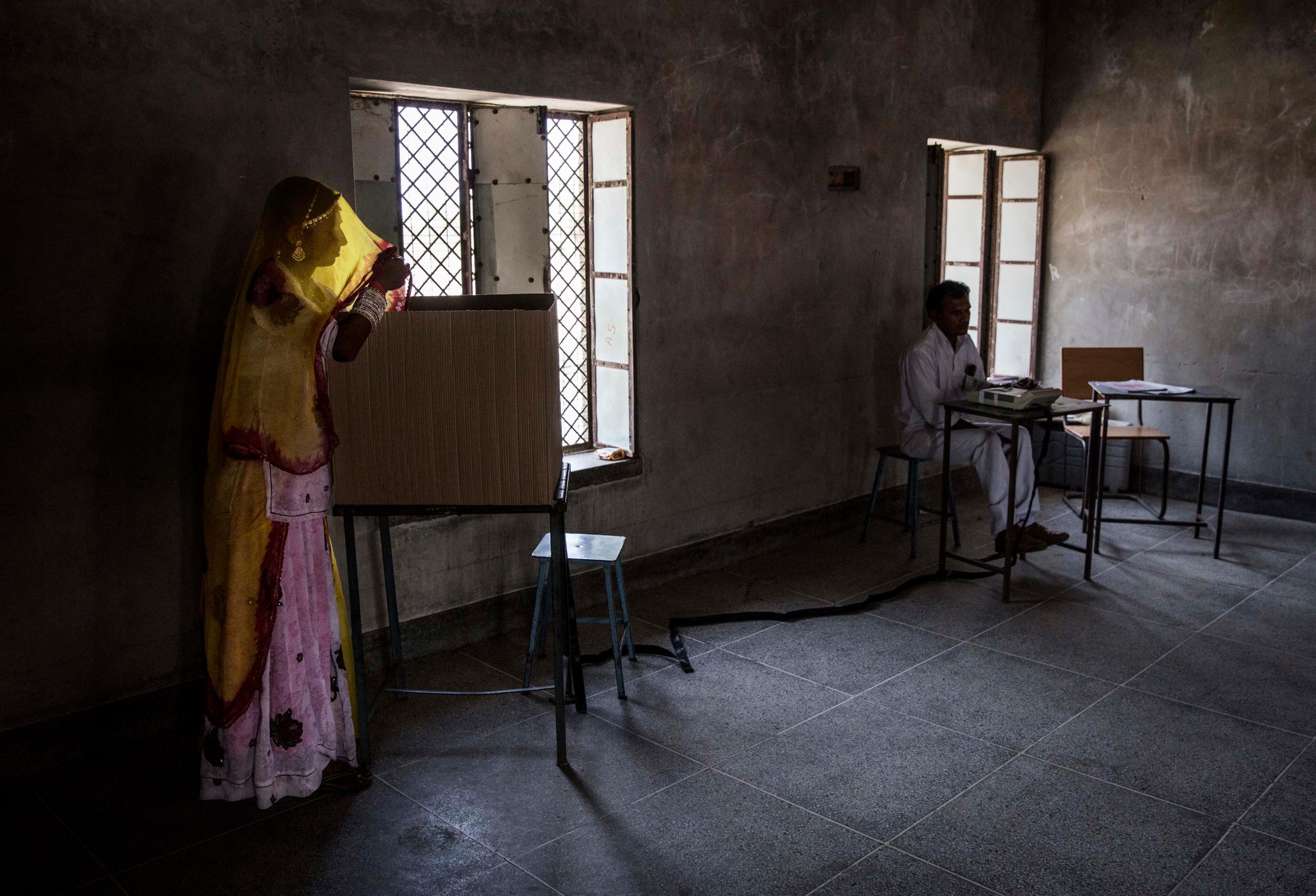

India’s Elections: Snapshots From the World’s Biggest Vote

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com