At 73, Kwon Dong-yul is tall and upright, a dapper figure in a cap, scarf and wool coat. Last Friday, he took me to a coffee shop in northwest Seoul, not far from the city’s World Cup stadium, and settled into his seat. He took off his hat, and looked out the window, before leaning in.

“I’ve lived 73 years, and I’ve seen a lot,” he said. “But this is the most dramatic situation of my life.”

Kwon and several hundred elderly South Koreans were about to set off for North Korea. Their caravan of cars, buses and ambulances, would cross one of the world’s most militarized borders, and continue on to the Diamond Mountain Resort. There, on North Korean soil, would be family members they hadn’t seen in six decades. There, with luck, would be Kwon’s big brother.

The Korean War separated hundreds of thousands of families. Since reunions started in the late 1980s, about 22,000 Koreans have come face to face with loved ones living on the other side, either in person, or via video call. But demand for spots outstrips supply, and applicants are aging. Some 130,000 South Koreans have applied for reunions since 2000. More than half have since died.

Many were surprised to see the latest round go ahead. The first meet since 2010—when the sinking of a South Korean naval vessel sent North-South relations to fresh lows—looked touch-and-go, because it overlapped with U.S.-South Korean military exercises, which Pyongyang considers to be hostile maneuvers. The north threatened to pull out at first—but relented after a round of high-level talks.

Nobody was more shocked to be heading north than Kwon. He didn’t even know that his brother was still alive until last year, when he got a call from his local police station.

“Do you know Kwon Eung-ryul?” they asked.

“He was my brother.”

“He is alive and wants to meet you.”

Kwon nearly dropped the phone.

In many ways, Kwon Dong-yul’s story mirrors the story of South Korea itself. He was born in the Korean countryside, in 1941, under Japanese colonial rule. His father was a civil servant, and the father of five—Eung-ryul, two daughters, another son, and Dong-yul, the youngest. They moved to Seoul in the run-up to the war.

In 1950, when northern forces occupied the city, Kwon was a 9-year-old schoolboy, his brother, a recent graduate with an excellent grasp of English. It was during the three-month siege that the eldest got separated from the family—drafted, they came to fear, to fight or labor for the north.

He doesn’t remember much else from that era. He knows his parents searched desperately, and that they didn’t find their son. He knows they never got over it. Kwon survived the war, married, and got a job at the Korean Development Bank. He started working just as the country’s economy was stirring to life.

In 1961, general Park Chung-hee seized power in a military coup and set about re-building South Korea’s economy. He nurtured massive conglomerates, or chaebol, that drove rapid industrial growth. In 1975, Kwon got a job with one of these giants, Daewoo, which was then in the business of building ships. He spent the next 25 years with his eyes fixed forward. “We worked, and worked and worked.”

Over the course of his adult life, South Korea was transformed. In the Seoul of his youth, the time between the winter and spring harvests was called the ‘Barley Hill’—you had to climb it to survive. Today South Korea is the world’s 11th largest economy and food and affluence are everywhere.

Kwon has lived well. His three daughters attended top schools and two went on to earn doctorates in the United States. After a stint as the CEO of a furniture company in the 1990s, he retired. Now he spends his time mentoring entrepreneurs, visiting friends, and hiking.

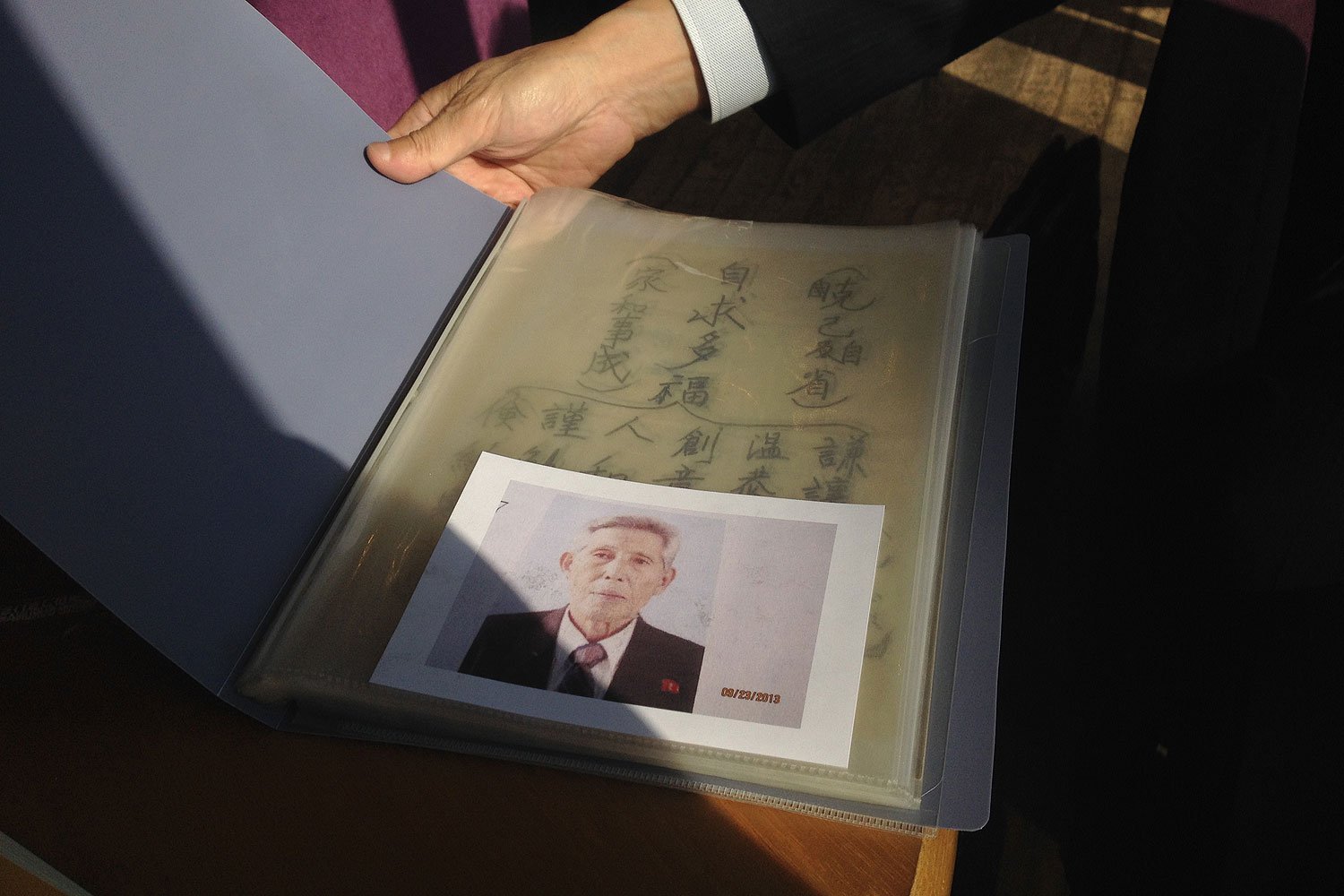

His brother’s life has been a blank. Last September, the Red Cross sent Kwon a picture of Eung-ryul. Kwon scrutinized it for clues. Eung-ryul looked good: clear eyes, full head of hair. He must have married, had kids. But how did he make it through the war, and the famine of the 1990s?

“When I meet him, the first thing I will do is thank him for living so long,” he told me that Friday in the coffee shop.

Two days later, Kwon met his brother, whom he recognized right away. But it didn’t feel real. “I wondered, ‘Is this man with a cane really a brother of mine?’ he says. “But when he started talking about our family, about our parents, I realized this is real, this is happening, it is him.”

Eung-ryul looked good for 88. At their first meal together, he ate heartily and drank several glasses of liquor, Kwon says. The first thing he did was apologize for failing in his duties as the eldest son. “He told me, ‘I should have looked after our parents, arranged their funerals and visited their tombs. But I could not, I am sorry.’”

Over five two-hour meetings and an hour-long goodbye, the brothers shared their stories. Kwon learned that his elder brother was indeed conscripted and forced north to fight. In what Kwon describes as a stroke of luck, Eung-ryul was shot and injured in battle. The bullet grazed his chest and passed clean through his left arm—a wound just serious enough to get him off the front line.

Because Eung-ryul spoke English, as well as some French and German, he was treated as a specialist and granted residence in the capital city, he told Kwon. He was assigned to work as a translator for a state-run radio station. It was there he met his wife, a fellow South Korean. They had three children together, and six grandchildren.

Many South Koreans were purged after the war, but Eung-ryul’s skill set kept him safe. He translated 12 volumes of Juche ideology—the socialist notions of self-reliance propounded by the nation’s revered founding father, Kim Il Sung The labor earned Eung-ryul a string of commendations.

“I think he was lucky,” says Kwon. “Because he translated the words of Kim Il Sung, nobody could touch him.”

There are lots of pieces missing. South Korean officials warned participants not to talk too much about politics, and reminded them that North Korean participants were briefed, maybe coached, for 10 days before the meeting. So they spent their time talking about the remote past, about their parents, and their siblings.

Because of economic sanctions, gifts are regulated. Kwon brought his brother cloth for a suit, and some winter clothes. He sent cookies and chocolate for the grandkids. Each delegate from the North brought their family member a local liquor used to honor ancestors at their graves. Kwon promised to visit their parents this spring, as is the custom. “I’ll tell them their eldest son is alive, that he has a family.”

Now back in Seoul, Kwon plans to share his story and to push for more reunions. He wants both sides to treat the matter as a humanitarian, not a political issue. North and South Korea should make personal exchanges a priority, he says. If they wait to resolve the nuclear question, or the issue of U.S. troops being stationed in South Korea, he will never see his brother again.

Odds are, he won’t anyway. “This should not be the end of the story, it should be the start,” Kwon says, pulling out his handkerchief. “I tried not to cry too much, but I could not stop crying when I said goodbye.”

It had been 64 years.

—With reporting by Stephen Kim / Seoul

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Emily Rauhala / Seoul at emily_rauhala@timeasia.com