There are few things that announce a photographer’s presence more than a camera’s flash does. That blinding flare of pure white light has been photographers’ beacon since its introduction to the medium in the late 19th century. From its earliest incarnation as a caustic fireball shedding light on social issues to its slick, shiny glow in fine art and fashion photography, flash has transcended genres to become one of the most divisive and distinctive features in the world of photography.

“It definitely polarizes the photography community,” said Amanda Bock, an assistant curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which has organized ‘Artificial Light,’ an exhibition dedicated to the controversial light source and the photographers who embraced it. “Some photographers, like Mark Cohen, use it in all of their work, while other photographers really shun it and feel that a photograph made by natural light alone is the way to make a good picture.”

Pulled almost entirely from the museum’s permanent collection, the show features work from an all-star cast of classic and contemporary photographers, from Weegee and Lewis Hine to William Eggleston and Andy Warhol — all artists with a distinctive way of looking at the world and a jarring and, at times, confrontational way of photographing it.

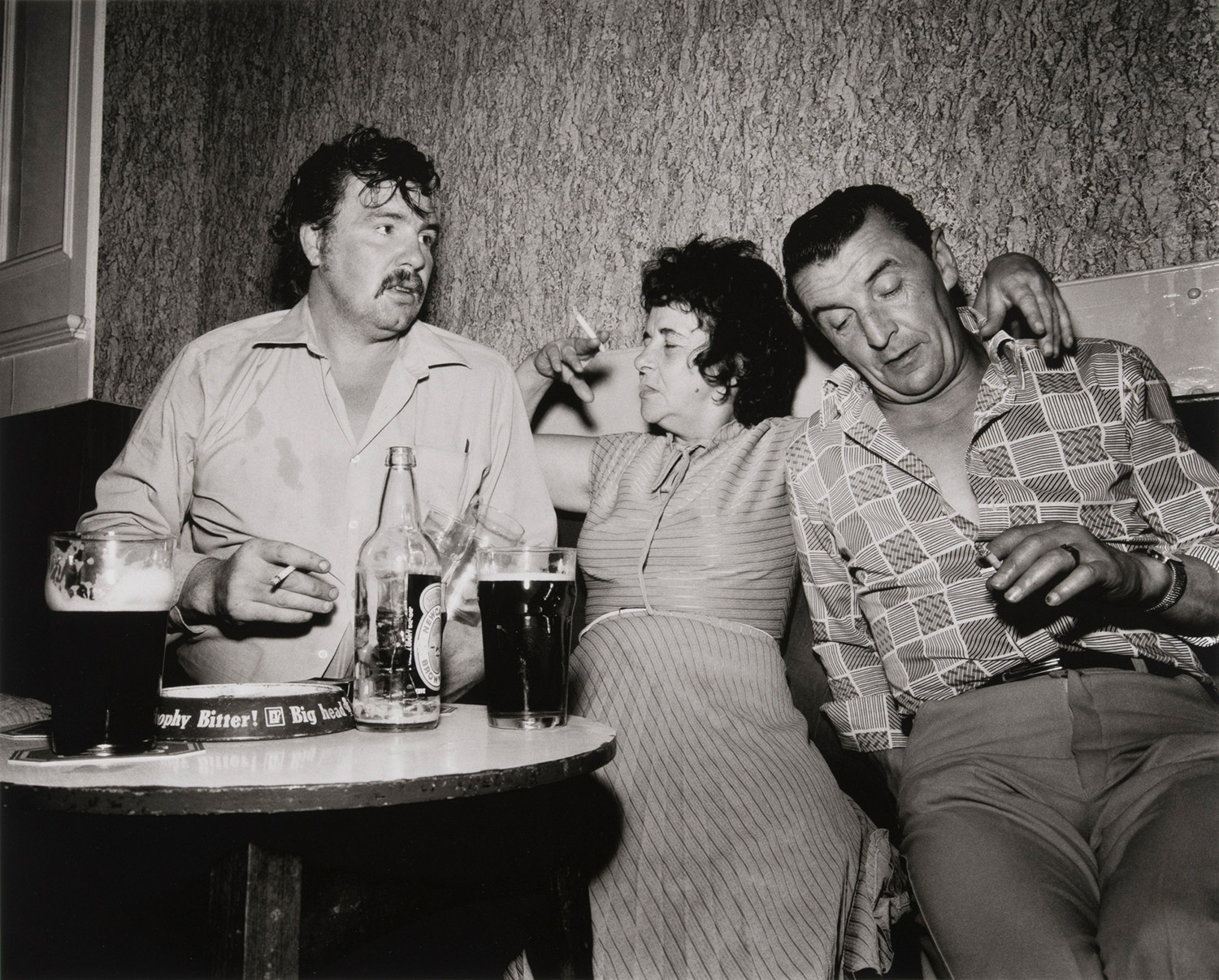

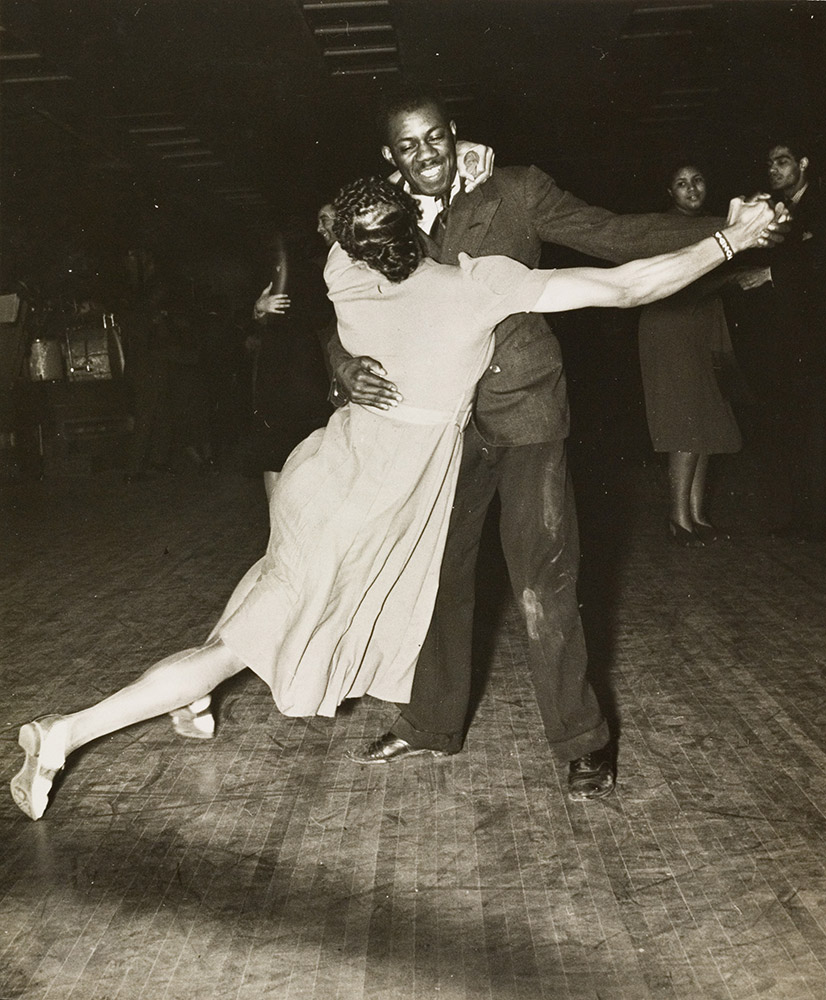

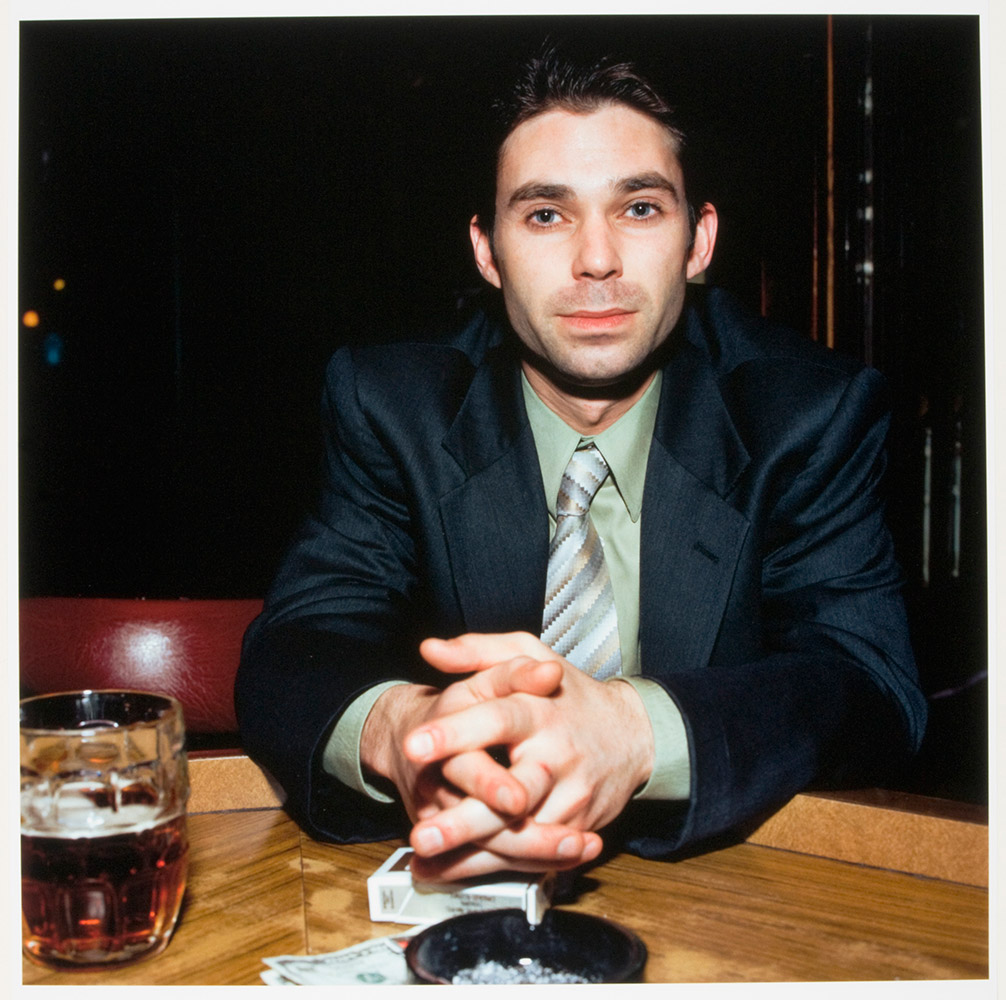

“There is a real overblown look at the world in these photos, where a lot of things are cast in deep shadows and the protagonist is made really evident by being washed out in this incredibly dramatic, white light,” Bock told TIME. “The flash actually becomes the moment itself. It consistently changes how our world looks.”

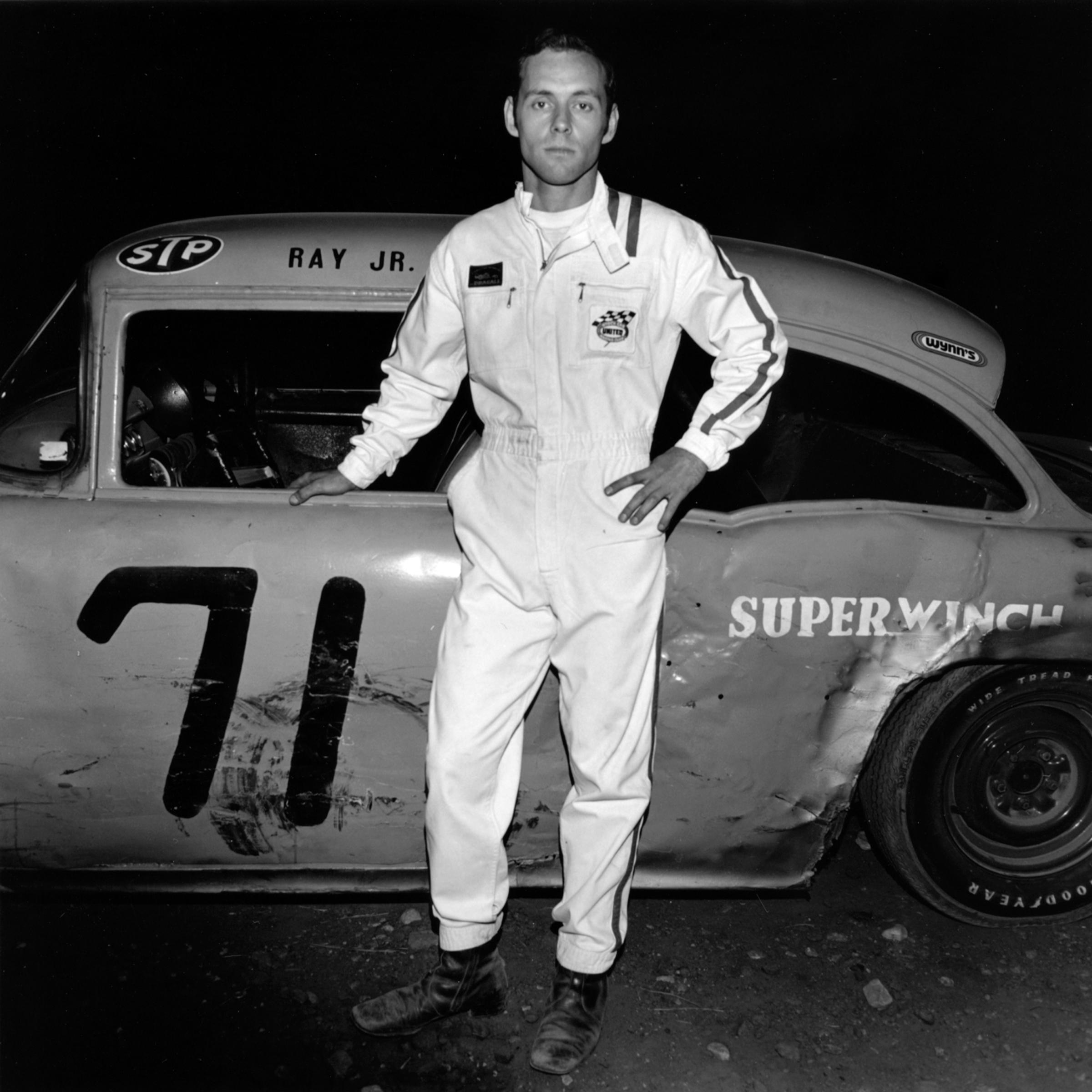

Photographer Henry Horenstein has used flash in his work since he first started shooting, having been inspired by Weegee and typically finding himself shooting in low-light situations. “I like the rawness, of it,” he said. “By lighting everything, it’s not a selective lighting. In a way the flash makes the picture, not the photographer. I don’t want to idealize or sentimentalize things. I want to show it like it is.”

While flash is, at its core, a technological accessory, Horenstien, who has written three photography text books, says it’s a tool that can open up an entirely new world for photographers, allowing them to control the kind and quality of light in an image, and expose things that would remain unseen otherwise. “It’s a far less prejudicial light that can be used in the simplest way even with the most sophisticated equipment,” he said.

Technology has always shaped how photographers make images, but few things have remained as prevalent as flash, despite the massive advances made in the field in the last 30 years. “There aren’t many things that unite an early glass plate picture with a digital image today,” Bock said, “but flash’s ubiquity is still part of the photographic world in 2014.”

Artificial Light: Flash Photography in the Twentieth Century is on show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art until August 3.

Amanda Bock is the Project Assistant Curator in the department of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Henry Horenstein is a photographer and a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design. He is the author of the classic instructional books ‘Black and White Photography: A Basic Manual’ and ‘Digital Photography: A Basic Manual’ and the monographs ‘Honky Tonk,’ ‘Show,’ ‘Animalia,’ and ‘Spoke.’

Krystal Grow is a contributor to TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @kgreyscale

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com