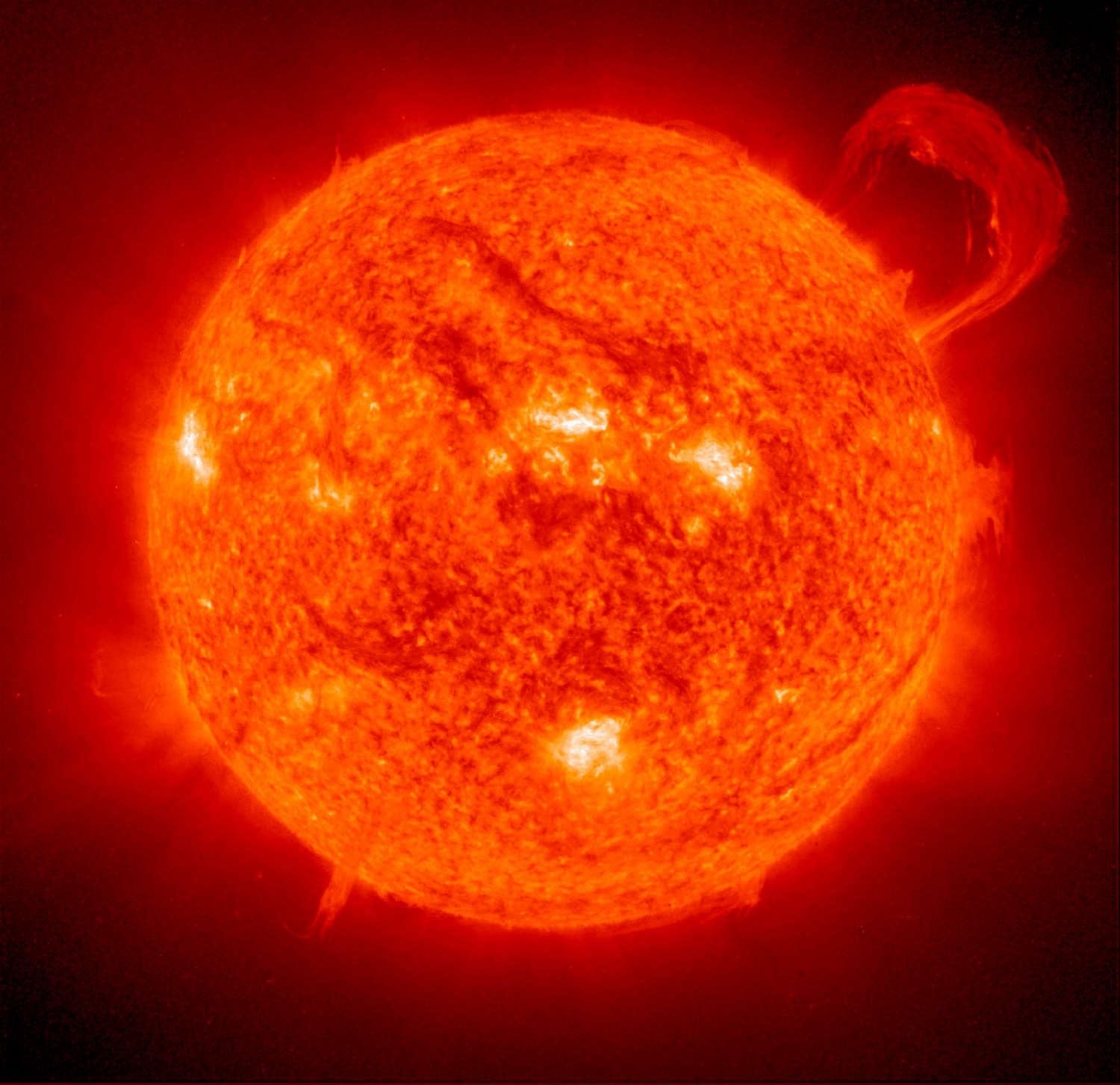

Astronomers have long known that stars are born, not one at a time in isolation, but in huge litters, all at once. In the Sun’s case, it happened about 4.6 billion years ago: a huge molecular cloud of interstellar gas and dust collapsed under the force of gravity, heating up until the densest, hottest knots of matter burst into thermonuclear flame and began to shine. The Sun has somewhere between 1,000 and 10,000 brothers and sisters, but over the eons they all wandered off into other parts of the galaxy, never to be seen again.

Or at least, not until now. A team of astronomers led by Ivan Ramirez of the University of Texas at Austin thinks it has found one of the Sun’s long-lost siblings— a star known HD 162826, which is floating through the Milky Way about 110 light-years from Earth, near the constellation Lyra. “We were really just doing this as an experiment,” says Ramirez, lead author of a paper on the discovery which will appear in the June 1 Astrophysical Journal, “to test our search technique. The fact that we actually found it makes this even cooler.”

The idea behind a search for solar siblings is straightforward enough. Each star-forming molecular cloud has a slightly different chemical composition, based on both its age and its location in the galaxy—a sort of cosmic DNA that carries over to the stars that emerge from the cloud. Find a star with that same DNA, and you’ve found a sibling.

In practice, though, it’s a bit more complicated. You can’t measure those fingerprints with absolute accuracy; two clouds might be similar enough to fool you. So while Ramirez and his team identified 30 probable candidates from earlier searches done by other astronomers, they went a step further: they took precise measurements of the candidates’ distance from the Sun and their motion, allowing them to reconstruct the stars’ paths through space since they began to wander off.

Once they’d done that, only HD 162826 made the cut. It’s not a twin of the Sun: HD 162826 is about 15% more massive than our home star. That’s no surprise, however since a given molecular cloud will give rise to stars of varied sizes. (Ramirez was also on a team that found a near-twin of the Sun in 2007—but that one is about a billion years younger, and was born from a different cloud.)

It’s actually surprising that the astronomers found even one solar sibling. The Sun’s brothers and sisters could have wandered thousands of light-years since their birth, nudged here and there by gravitational encounters with gas clouds and with other stars. “Estimates of how many we’d be likely to find here in the solar neighborhood have been quite pessimistic,” says Ramirez—one at the most, and quite possibly zero.

Finding just one solar sibling isn’t going to tell astronomers all that much by itself, and since a star’s travels are difficult to reconstruct without knowing precisely where it is today and how it’s moving, it’s currently impossible to search for the Sun’s blood relatives further out than about 300 light-years. “We don’t have accurate distances any further than that,” says Ramirez.

But a new European satellite called Gaia, launched last December, will change all that. It’s slated to get precise information on the positions, distances, chemical abundances and more for a billion different stars, reaching to the center of the Milky Way, thousands of light-years away our solar system.

Armed with that information, Ramirez and other astronomers will not only be able pinpoint many more of the Sun’s long-lost siblings, but they’ll also figure out the common origin of thousands of other stars. “Grouping stars according to their origins,” he says, “and understanding how they spread out over the past few billion years, is really crucial to understanding how the Milky Way has evolved.”

It’s also oddly reassuring to know where the Sun’s family has ended up after so much time. HD 162826 has been under observation for some time, purely by coincidence, to see if it might have planets. Nothing has turned up yet, but the searches aren’t sensitive enough to detect Earthlike planets. It’s not impossible that we’ll someday learn that this first rediscovered Solar sibling has children—and that Earth itself has a first cousin.

See the Astronomical League's Most Beautiful Photos from 2014

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com