On Wednesday, Facebook announced a major change to its sign-in button, which lets you use your Facebook credentials to log into other apps and websites.

Instead of allowing developers to help themselves to your personal data, Facebook will let users decide what data, if any, to share. You’ll even be able to sign in through Facebook anonymously, so the app or website knows nothing about you.

In making this change, Facebook is making a bigger commitment to saving us from password hell. If Facebook can get users to realize that they don’t have to share any data with other apps, people might actually use the big blue “sign in with Facebook” button instead of creating yet another username and password.

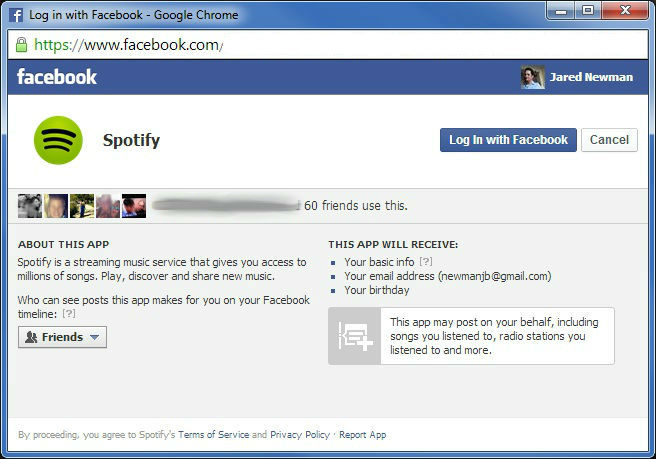

Currently, signing in with Facebook is kind of scary. Here’s what happens, for instance, when you try to connect Spotify to your Facebook account:

By default, it’s asking to share your activity with friends and access a bunch of personal data. You can make your activity private, but there’s nothing you can do about the data. And this type of disclaimer comes up with every new sign-in.

Even if you don’t mind sharing your musical tastes with friends on Spotify, the message is clear: When you sign in with Facebook, you’re always sharing something. That big blue button becomes a turn-off, so instead of using it for new apps or sites, you end up creating more usernames and passwords. Or, more realistically, you reuse the same credentials you’ve used everywhere else, giving yourself one more password to change the next time a site gets hacked.

Facebook recognizes that its push to make everything social has scared people away. “When we were a smaller company, Facebook login was widely adopted, and the growth rate for it has been quite quick,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg told Wired. “But in order to get to the next level and become more ubiquitous, it needs to be trusted even more.”

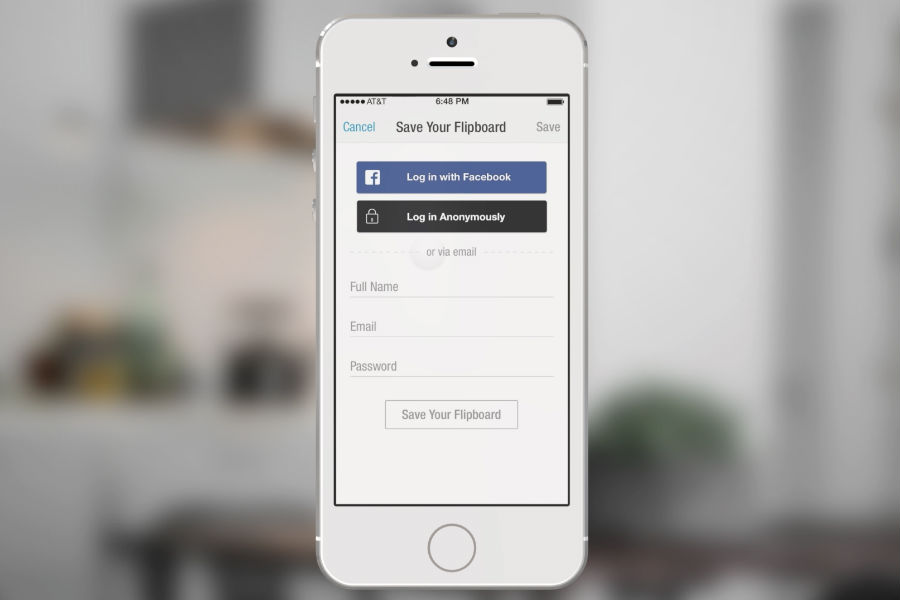

Facebook’s solution is to give users a couple of new options: If they sign in with Facebook, they can now control exactly what gets shared with the app. Or, they can use a new “Log in Anonymously” button, and share nothing. In either case, if you’re already signed into Facebook elsewhere on the device, you don’t have to enter a username or password at all.

Enter Google+

Facebook wasn’t alone in its pursuit of social sign-ins. Last year, Google launched a similar product, allowing users to click the big “Sign in with Google” button on supported apps and sites. These buttons also show a logo for Google+, Google’s own social network.

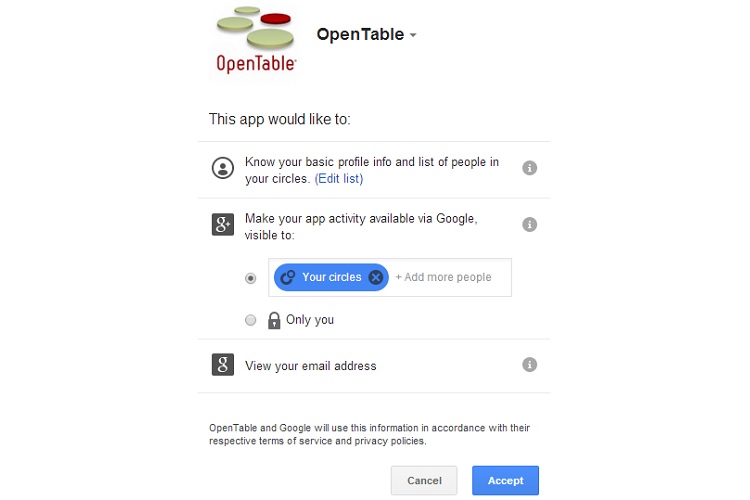

OpenTable was one of Google’s first partners. Here’s what you see when you log in with Google instead of creating a new OpenTable account:

This is only marginally better than Facebook’s version. Your activity is still visible to everyone by default, and OpenTable still gets access to your e-mail address. The only difference is that you can prevent OpenTable from seeing your friends list and basic profile info, but this option is buried behind another dialog box. Every time you sign into another app or site, you have to deal with these options.

Again, the message is the same: If you want to maintain some privacy, you should just avoid Google+ sign-in.

But there are signs of change in the air. Rumor has it that Google will de-emphasize Google+ as a product, which could lead to a change in how sign-ins work. In fact, Google is now testing a more generic blue “Sign in with Google” button, but only for developers. As with Facebook, Google may have more success with its sign-in button if it scraps the social element.

The Case for a Master Key

In a sense, tying lots of accounts to a single Facebook or Google sign-in sounds like a security nightmare, because one breach could bring everything down.

The flip side is that by having a master key, you can concentrate on making it much stronger than your average username and password, thereby strengthening security across many other sites. You could set a longer, better password than you would on other sites, or you could enable two-factor authentication, which lets you authorize only specific devices to access your account.

Two-factor authentication is somewhat of a hassle now, but could become easier with the rise of wearable technology (such as smartwatches) or biometric sensors (such as Apple’s TouchID fingerprint reader), which could provide an extra layer of authentication on top of your password.

Even if you don’t take these extra precautions, both Facebook and Google will alert you to suspicious activity — say, when a login occurs in a faraway location, or when your password gets reset — and you can even choose to get these notifications by phone.

But the master key will only take shape if app developers get on board, and if users feel comfortable with the idea. Google and Facebook have enough developer influence to make the former happen, and if they stop being so hell-bent on making everything social, users might actually follow.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com