If you were a kid in the 1950s, and you got nightmares from a story in a horror comic book, you have Al Feldstein to blame. If you were a kid in the ’60s or ’70s, giggling at MAD’s prankster wit, you have Feldstein to thank. And if you’re a kid today, you are the beneficiary of the gaudy tastes — or lack of taste — that he incited as the editor of Vault of Horror, Tales from the Crypt and MAD. What Marvel’s Stan Lee has been to the superhero culture, Feldstein was to horror and humor in his years at publisher William Gaines’ EC comics. Feldstein’s metaphorical children range from Stephen King to Stephen Colbert, from Quentin Tarantino to the skewering clowns of Saturday Night Live.

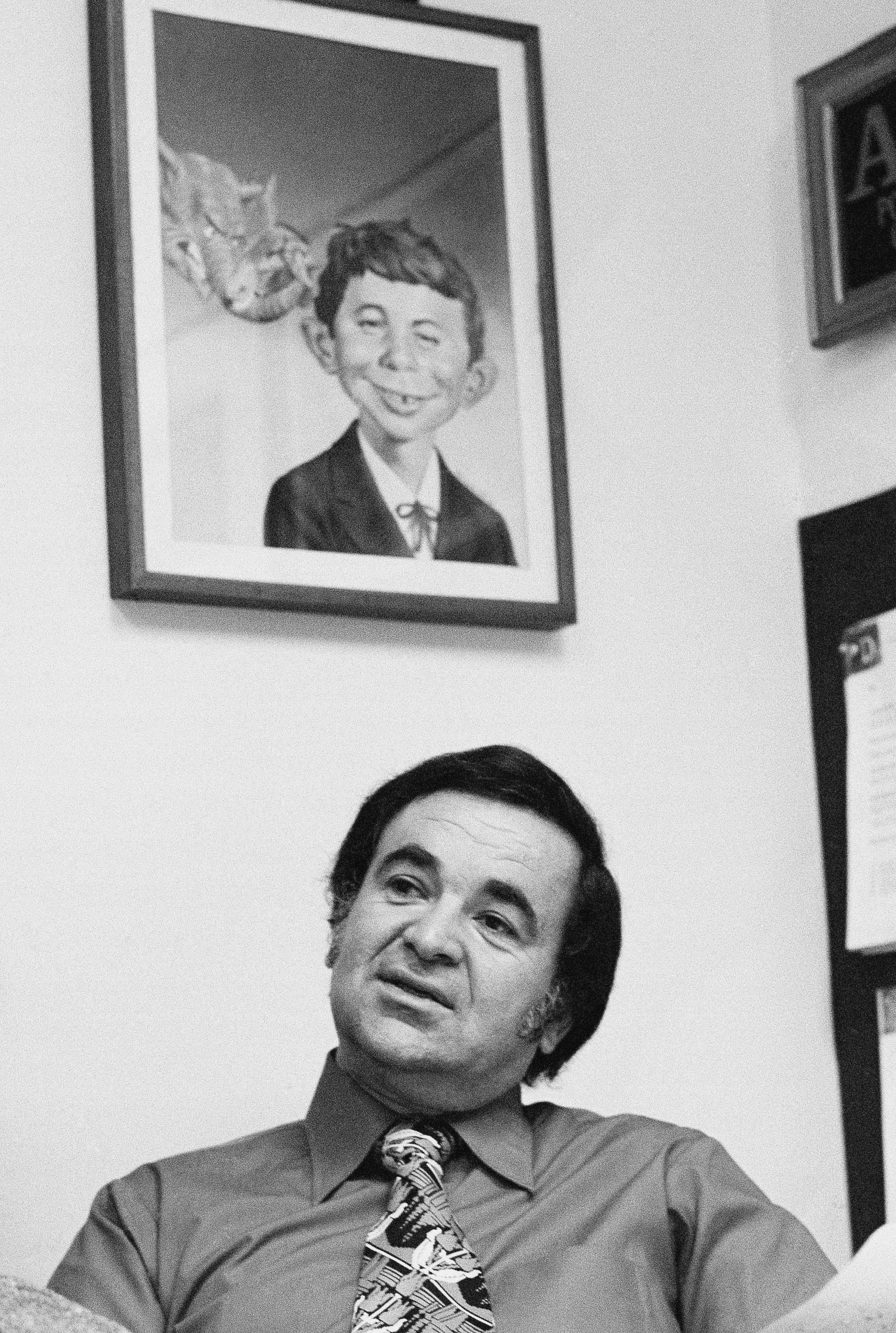

Feldstein, who would edit MAD for 29 years, in the decades of its greatest popularity and influence, died Tuesday at his home near Livingston, Montana. He was 88.

(READ: Kurt Andersen’s tribute to MAD publisher William Gaines)

Under its founding editor Harvey Kurtzman, and then under Feldstein, MAD became for the brain what rock ‘n roll was to the groin: a pulse for irreverence, suspicion, internal insurrection. The laughs that the magazine provoked in curious boys (it was mostly a guy thing) were the intellectual equivalent to the screams Elvis Presley elicited from pubescent girls. Connecting with the MAD zeitgeist meant plugging into the wide world of culture — because, first and foremost, MAD was the medium that kidded the media.

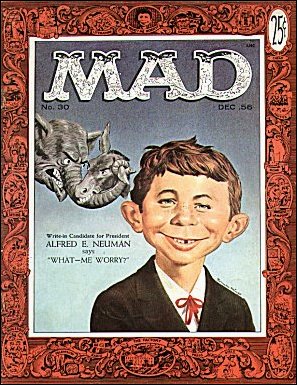

A ’50s comedy genius, Kurtzman created MAD as a comic book in 1952 and turned it into a magazine three years later. But Feldstein codified it. When Kurtzman was fired by Gaines, he took along his brilliant illustrators: Bill Elder, Jack Davis and Wally Wood. Stripped of the men who made MAD, Feldstein quickly assembled “the usual gang of idiots” who would define the magazine’s tone. He also knew what to do with an old photo of a goofy, smiling kid that Kurtzman had adopted as the magazine’s mascot, eventually calling him Alfred E. Neuman. Feldstein put the character on the cover in 1956, as a write-in candidate for President, and he has been MAD’s cover boy ever since.

(READ: Corliss on Harvey Kurtzman and MAD)

Without Feldstein, the magazine may never have survived, let alone thrived. “When Kurtzman left here and Al came back and took his place,” Gaines told the young EC historian Fred von Bernewitz in 1957, “one of the things we definitely decided to do was: let’s sell MAD, first. And let’s try to make it a good worthy magazine second.” The ever-efficient Feldstein got the magazine back to its bimonthly schedule — for a while it published eight issues a year — and quickly assembled a reliable batch of contributors: writers Frank Jacobs, Stan Hart, Larry Siegel and Arnie Kogen and writer-artists Don Martin (“MAD’s maddest artist”), Sergio Aragones (“Spy vs Spy”), Dave Berg (“The Lighter Side of…”) and Al Jaffee (the back-cover “MAD fold-in). The magazine’s circulation grew from 750,000 in Kurtzman’s day to 2.3 million in the mid-1970s. After Feldstein’s departure in 1984, the circulation shrank to about a tenth of that.

Yet MAD was only the second act in Feldstein’s career. His primal influence was from 1950 to 1954, writing and editing the EC horror comics that thrilled young readers and outraged conservative psychologists and members of the U.S. Senate.

(READ: MAD Magazine at 50)

Born in Brooklyn in 1925, Feldstein was 22 when Gaines hired him in 1948. What a smart pickup! Feldstein was every boss’s favorite employee: a hard-working idea man with inexhaustible energy and a nose for the market. Within two years, he and Gaines had dumped their line of romance and Western comics for such titles as Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, Weird Science, Weird Fantasy and Shock SuspenStories. Feldstein wrote and sketched virtually all the stories. For a few years he was filling seven complete magazines every two months, often illustrating stories and drawing the covers.

For precocious children of the early ’50s, the EC horror line was a passkey to the forbidden. Kids felt scaredy-brave, both by subjecting themselves to horror stories and by daring to read something that might be condemned by their parents. These nervy, rebellious frissons originated in Feldstein’s storytelling savvy and gift for lovingly elaborate narration. As he recalled: “The old joke was that I got to write such heavy captions and balloons that the characters had to be drawn with a hunchback.” Though Davis, Johnny Craig, “Ghastly” Graham Ingels and other EC artists had distinctive styles, Feldstein’s words and grisly plots sold the magazines. His sagas of unearthly vengeance and pummeling descriptions of extracted body parts gave the stories their lingering, gruesome, often funny chill.

“By mid-1953 business at EC was astonishing,” writes Maria Reidelbach in Completely MAD: A History of the Comic Book and Magazine. “The Haunt of Fear, The Vault of Horror and … Tales from the Crypt had a circulation of 400,000 copies each.” But the glory gory days couldn’t last. In his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent, the clinical psychologist Fredric Wertham linked the rise in teenage crime to the pernicious influence of comic books. “Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic book industry,” Wertham told the Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency headed by Estes Kefauver.

(READ: The Power and the Gory of EC Horror Comics)

Gaines also testified at that hearing, defending the influence of the EC line on children by saying, “I don’t think it does them a bit of good, but I don’t think it does them a bit of harm, either.” The subcommittee condemned “those materials offered for children’s reading that fall below the American standard of decency by glorifying crime, horror, and sadism,” and within months the comics industry adopted a censorship code that Gaines refused to accept. His horror magazines were dead. All he had left was MAD. And when he fired Kurtzman, the only one to save him was Feldstein, who shepherded the magazine through its palmiest period.

Feldstein also agitated to expand the MAD brand. He told Jenn Dhigos on the Classic-Horror website that he proposed starting a MAD TV show (this before Saturday Night Live), accepting “real (but humorous) ads to subsidize a four-color magazine, and launching “a ‘live’ and ‘animated’ VHS version of MAD (today, it would be on CD!).” Gaines nixed all these ideas. Feldstein said that, after he left MAD, Gaines “started to cut me out of the history of EC … and MAD! …I didn’t even get screen credits for all of my stories that they adapted [in the Tales from the Crypt TV series]. Bill saw to that.”

He retired to Wyoming, and then Livingston, where he became a serious painter specializing in Western themes. Perhaps Feldstein had tired of giving kids belly laughs and stomach tremors. Or maybe his 36-year stint at EC was less a calling than a job, finally earning him enough money to pursue his artistic dream. In his last years he would send out funny, fulminous emails decrying America’s state of disunion. But we’ll remember him, fondly and gratefully, with the phrase he ended each message:

“MADly yours,

Al Feldstein”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com