Despite its vaunted intelligence-gathering capability, the U.S. military was surprised when enemies in Iraq and Afghanistan began building and deploying roadside bombs to kill and maim U.S. troops.

It got so bad that a soldier asked Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld nearly two years into the Iraq war why U.S. troops were forced to defend themselves against such improvised explosive devices with homemade “hillbilly armor.”

“You go to war with the Army you have,” Rumsfeld told the soldier, “not the Army you might want or wish to have at a later time.” It took the Pentagon three more years before Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles finally began trickling into Iraq.

While the troops were waiting for that armor, the Pentagon was also neglecting to track the traumatic brain injuries caused by such blasts, a new medical study says. TBIs—the “signature wound” of the post-9/11 wars—are tough to diagnose and treat. Without a good accounting of those who experienced a TBI, those challenges multiply.

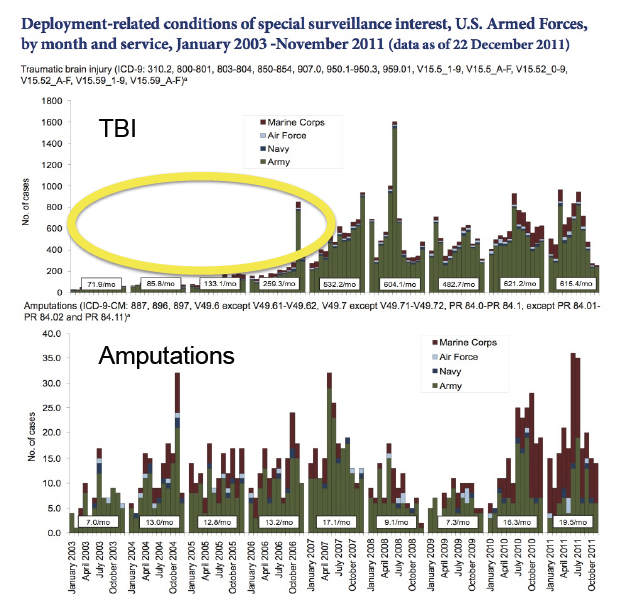

The report’s authors, using amputations as a proxy for TBIs, conclude that the military documented only one in five TBIs estimated to have affected U.S. troops between 2003 and 2006. Responding to legislation, the Pentagon began tracking TBIs more closely beginning in 2007.

Overall, during the eight years spanning 2003 to 2010, the study estimates that 32,822 active-duty troops suffered undocumented TBI wounds. That’s more than the 32,176 documented by the Pentagon over the same period of time. “This analysis provides the first estimate of undocumented incident TBIs among US military personnel serving in Iraq and Afghanistan” before Congress demanded the improved counting, the report says.

Such missing diagnoses are important, says the study, conducted by a pair of Johns Hopkins University health experts. Undocumented TBIs could lead to troops being booted from the military as malingerers or for personality disorders—discharges that could restrict their access to care from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

For those remaining in uniform, it could lead to additional combat tours, boosting their chances of a second TBI and the “visual and auditory deficits, posttraumatic epilepsy, headaches, major depression, and suicide risk” that accompany multiple TBIs, according to the study. Even a so-called “mild” TBI can rattle the (helmeted) brain inside the skull, leading to a host of maladies including memory loss, cognitive deficits, mood volatility, substance-abuse disorders, personality changes, sleep difficulties and possibly post-traumatic stress disorder.

“In recent years, the U.S. military has generally been reactive, rather than proactive, in responding to public health crises, including suicide, psychotropic drug misuse, and gaps in wounded warrior care,” says Remington Nevin, a co-author of the study. “Public-health leaders within the Department of Defense have a troubling history of having epidemics and programmatic deficiencies identified only by outsiders long after the time to act has passed, rather than having these identified internally in time to mount an optimally effective response.”

A top Army psychiatrist at the time says troops minimized the issue, and their leaders weren’t seeking it out. “Soldiers did not want to come forward, for fear that would be taken out of the fight, or thought to be malingerers,” says retired Army colonel Elspeth Ritchie. “And we — the medics and the line [officers] — were not looking for it.”

The authors used an interesting yardstick to estimate the number of undocumented TBIs: they calculated them by developing a mathematic formula that established a relationship between amputations and TBIs, based on the wars’ later years when the Pentagon was more rigorously tracking TBIs. Unlike TBIs—the so-called “invisible wounds” of the nation’s post 9/11 wars—amputations are visible and easily counted.

IED blasts cause most TBIs and amputations, making missing limbs a good tool to estimate the missing TBIs, says the paper, by Rachel Chase and Nevin of Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health. “Including amputation counts in the model as a proxy for injury causing events is appropriate, given strong clinical and ecological evidence of common mechanisms of injury” for amputations and TBIs, they write in an article in the Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation slated to be posted next week.

Too often, wars’ impacts aren’t gleaned until years later. Mustard gas experiments poisoned thousands during World War II. Cold War nuclear-weapons tests are suspected of causing cancer. Agent Orange was the ticking time bomb in Vietnam—the Department of Veterans Affairs is still adding to its list of medical consequences. Gulf War Syndrome stemming from the first war with Iraq, in 1991, remains a mystery. Traumatic brain injury is simply the latest in the list of war’s unintended repercussions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com