It’s not the most original premise in cinema history: A soldier visits an inn and encounters the innkeeper’s daughter, and the two then have sex. The actors portraying the characters in this vintage black-and-white movie look more like confused amateurs than confident professionals in their awkward onscreen chemistry. At this point, if you’re still curious to see this, good luck — it’s very likely you won’t be able to find an actual print of it, let alone on DVD or online.

But this particular French movie, A L’Ecu d’Or ou la bonne auberge, made in 1908, does have some historical significance: it is believed to be one of the first-ever adult films. That piqued the curiosity of Charles Thompson, a.k.a. Black Francis, the singer of the alternative rock band Pixies.“I just began to kind of Google that information to see what came up,” Thompson tells TIME. “It seemed like the same bit of information kept coming up about this title, A L’Ecu d’Or ou la bonne auberge, which means sort of like, ‘The Gold Coin’ — it’s like an old form of French money — or ‘The Good Inn.’”

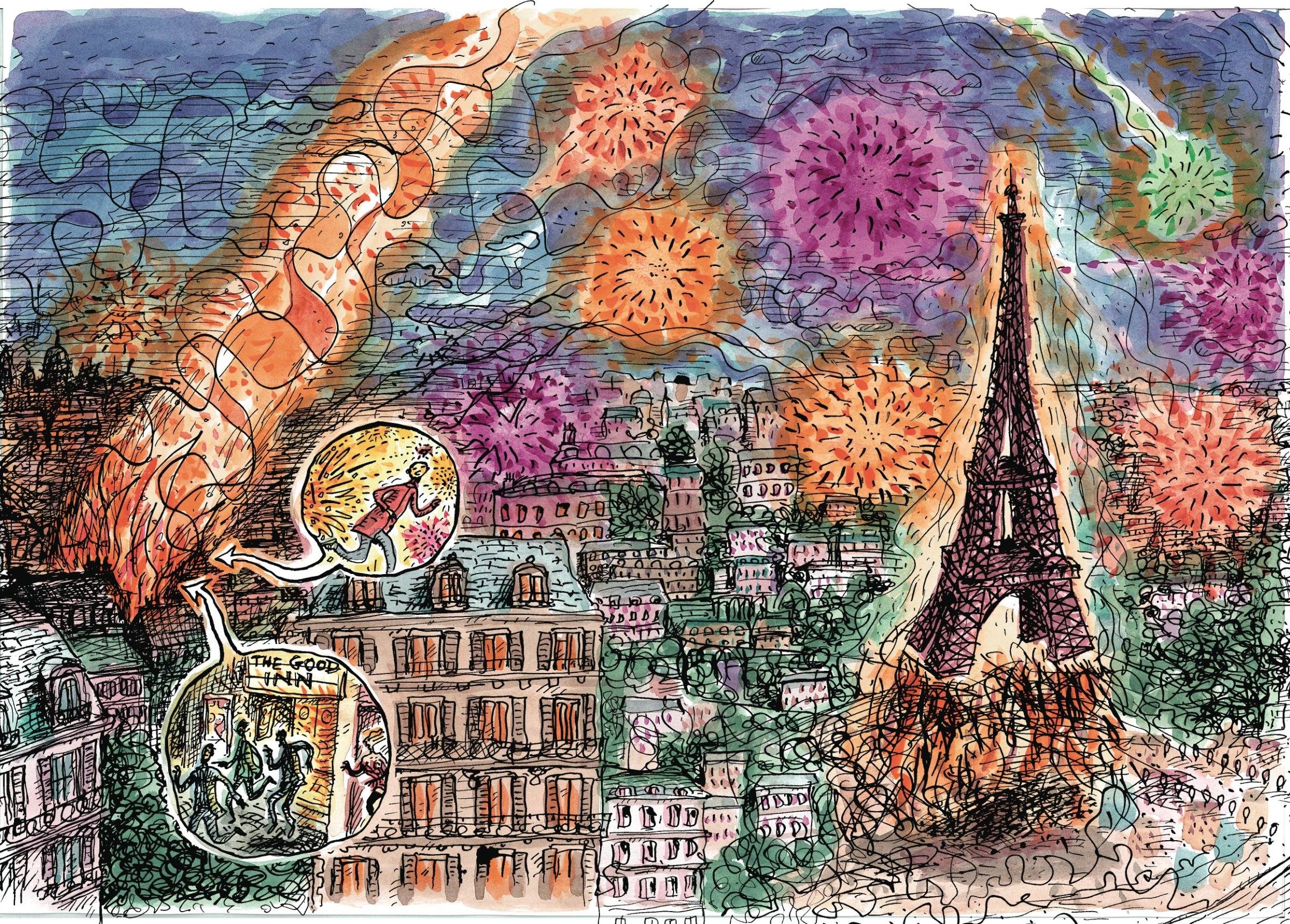

Thompson’s interest in A L’Ecu d’Or ou la bonne auberge served as an idea for a hypothetical movie, and he even recorded a few demo songs as a soundtrack. Discussing the idea in 2010 at a cafe in Austin, Texas with the writer Josh Frank, Thompson began to consider making an actual movie. The result: the two collaborated on a newly-published graphic novel also titled The Good Inn (with whimsical illustrations by Steven Appleby, who had provided the artwork to the Pixies’ 1991 album Trompe le Monde), based on the stag film.

Set in 1907, the book The Good Inn chronicles the adventures of a French soldier, simply named Soldier Boy, who goes on a journey after surviving the explosion of the battleship Iena. It does follow the original film’s plot in that he does have a sexual tryst with the innkeeper’s daughter named Nicole. But then a surrealist fantasy element is introduced — as he makes love to Nicole in the dark, Soldier Boy notices a light coming from a pinhole on the wall. Looking through it, he sees his own doppelganger and a woman resembling Nicole in bed while being observed by other people in the room. When Soldier Boy looks through the pinhole again, he sees no one in the room, except what appears to be a movie camera. It leads to a chain of events in which reality and fantasy intersect.

Thompson and Frank were unable to find a print of the extremely rare original movie, but they filled in the gaps for the book’s story through research about early French cinema. The authors also incorporated actual people from the era into the book — such as Albert Lear, one of the first French pornographic filmmakers, portrayed as a maverick who saw potential in the medium. “I really want to see a print of it for the purposes of this film script that we are writing because I don’t know what we can glean from it, but we might be able to get something,” says Thompson. “I don’t know if we’ll get a name or just some little thread to fill in the blanks a little more. I’ve been a little bit unsatisfied in that department.”

“I would like to see the film because I would like to see the credits,” says Frank. “I do want to see the names. But as far as actually seeing the movie, I like the fact that we have this freedom right now to make up a lot more. I feel like if we actually had the movie, maybe it would close us off from what we actually want to do.”

Soldier Boy is the book’s main protagonist; he gets involved in a series of unexpected events as he comes to grips with a ship explosion that killed his friend and the shock of seeing his lookalike in the adjoining room at the inn. “I think [Twilight Zone] is the greatest influence on me in terms of, ‘So, what do we do with this idea? What does Soldier Boy do?'” he says. “Well, he finds a hole, and there is a doppelganger. He doesn’t know why this is happening to him.”

“The real starting point for the invention of this idea was that Charles put together two separate true histories,” Frank says. “One being the explosion on the Iena, and the other being the first pornographic film starring a soldier. And I think the big starting point was, ‘What’s the back story of this soldier?’ and the other thing that interested you was the explosion on this ship, which happened in the same year.”

The Good Inn coincides with the release of the Pixies’ first new album in 23 years, Indie Cindy. (It’s also the first record without original bassist Kim Deal, who left the band in 2013.) One of its new songs, “Bagboy,” originated from the song cycle that Thompson had worked on for the proposed movie project. “As a band, we actually played a lot of the music that was around this song cycle,” he says. “But none of them have ever ended up as part of a record. I’m glad they haven’t merged too much. We didn’t know whether or not the book or the movie of how much it was going to dart around time. I haven’t been able to decide whether the music should be anachronistic or not, or if it should represent that time. I’m moving away now from being anachronistic.”

With the book now published, both authors are in the process of getting their film made and assembling a production team. “We had a couple of meetings,” Thompson, who admits he has fallen in love with the characters in The Good Inn, says. “We’re working on the script, we got a couple of people involved. There’s a music producer that I’m starting to work with, and another songwriter – a French woman – to help me compose some French libretto for the songs.”

“We thought this warrants a piece of art that you can hold in your hands,” says Frank. “But also it was the idea that by doing this book, this crazy movie idea might come together. I feel personally that it completely has.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com