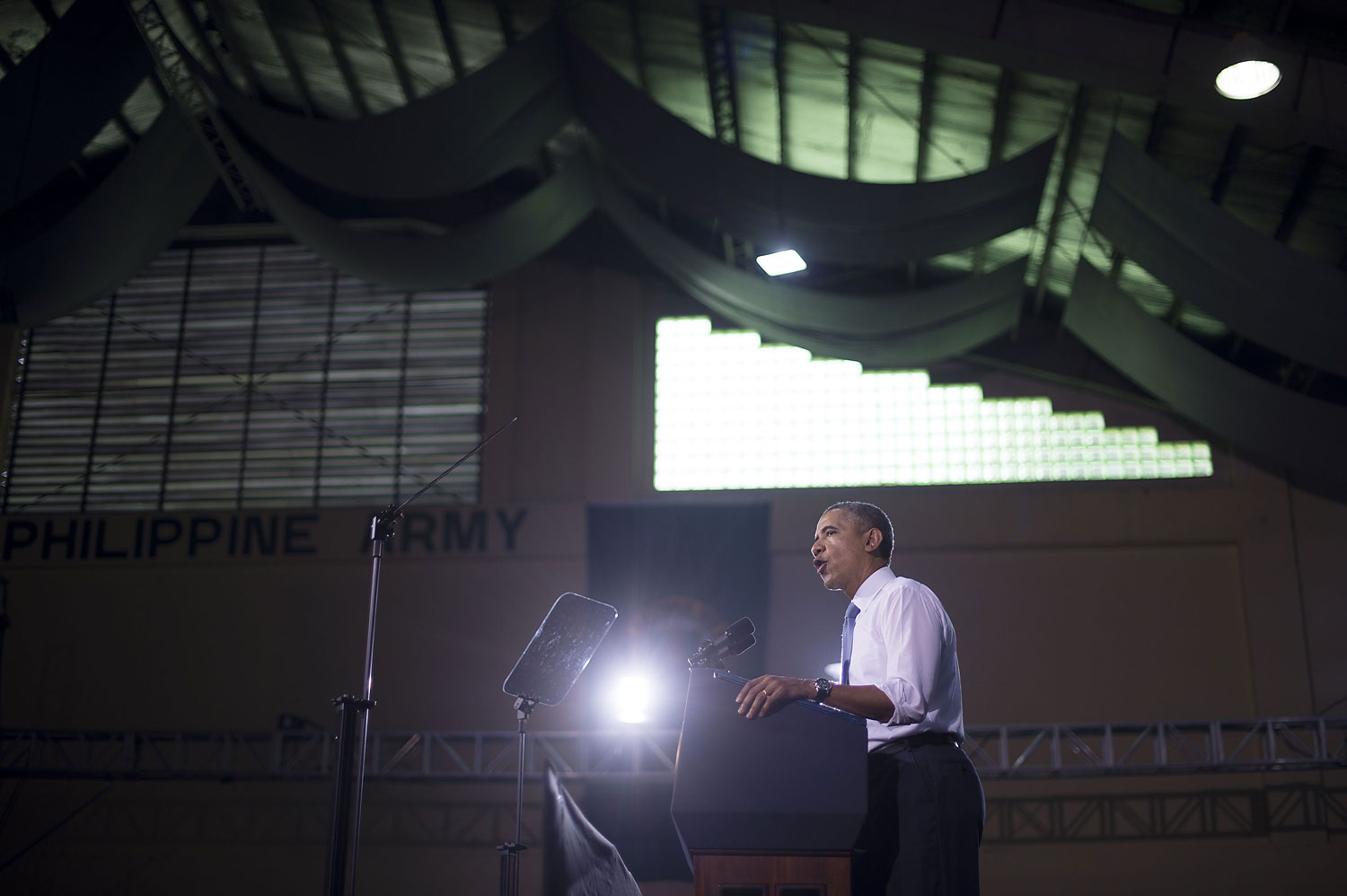

U.S. President Barack Obama’s four-nation tour of Asia ended Tuesday with a speech at Manila’s Fort Bonifacio. Standing in a gymnasium packed with camo-clad soldiers, Obama spoke about the 10-year military pact signed Monday. The agreement, which was the centerpiece of his visit to the Philippines, will give U.S. planes, warships and troops greater access to the archipelago. Many Filipinos see the deal as a counter to China, with which the country is locked in a bitter maritime dispute. Obama insists it is not. “Deepening our alliance is part of our broader vision for the Asia-Pacific,” he said.

Left unsaid, of course what this “vision” for Asia means for the region’s rising power, China. The recurring theme of Obama’s tour was that it was not about Beijing. This was a friendly visit, full stop — and it was indeed full of well-wishes and vows of trust. Yet the more Obama denied it was about China, the less it rang true. Through stops in Japan, South Korea, Malaysia and the Philippines, China loomed large — the proverbial dragon, or panda, in the room.

The mixed messaging underscores the challenge of one of the Obama Administration’s signature foreign policy initiatives: the so-called pivot to Asia. The plan calls for the U.S. to shift resources away from the Middle East to East Asia, where they see more opportunity ahead. But China is also expanding its influence in the region. And Obama chose to visit four countries that are wary of China’s rise.

“President Obama obviously wants to avoid any appearances that this is part of a new Cold War with China,” says Mark Thompson, director of the Southeast Asia Research Centre at City University of Hong Kong. “But this is a tricky balancing act because this is increasingly how the U.S.’s traditional allies that he is visiting are viewing things.”

Take Japan. President Obama’s visit to Tokyo came amid ongoing Sino-Japanese territorial disputes. A set of rocks, called the Senkaku in Japanese and the Diaoyu in Mandarin, is administered by Japan but also claimed by China. The U.S. maintains a neutral stance on their ownership. But while in Tokyo, Obama said for the first time that the islets are covered by the security treaty that commits the U.S. to defend Japan should it be attacked — a boon for hawkish Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, but not great news for the Chinese.

It was a similar story in the Philippines, where the signing of a military pact and a speech to soldiers did much to counter the notion that the visit was, as Obama insisted, not about countering China, but rather, deepening long-standing ties. “The Obama strategy is military deterrence and balancing, combined with political and economic engagement,” says Minxin Pei, a China scholar at Claremont McKenna College, in California. “The problem with this strategy is that the Chinese tend to take the engagement part for granted and see the deterrence part as pure containment.”

Even in South Korea, which is not embroiled in a territorial dispute with China, Beijing was, at times, a silent presence. In Seoul, Obama announced that the U.S. and South Korea agreed on a binational defense team that, in the event of war, would put South Korean troops under U.S. control. Citing signs that North Korea plans to conduct another nuke test, Obama warned the U.S. would “will not hesitate to use our military might” to defend its allies. Yet there is a growing sense that to move forward with North Korea, it is China, not the U.S. or South Korea, that holds the key.

And then there’s Malaysia, a country with whom neither the U.S. nor China has particularly strong ties. A recent editorial in Global Times, a Beijing-backed newspaper, claimed the Obama visit — the first by a sitting President since Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966 — was a reward for Malaysia adopting a harder stance toward China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. If that’s the case, Obama certainly isn’t saying. But he certainly stepped lightly in Kuala Lumpur, choosing not to visit opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, who is appealing charges of sodomy that he says are politically motivated. The President also failed to convince Malaysia (or Japan for that matter) to commit further to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-country trade bloc that does not include China.

Still, the host countries gained much: Japan’s Abe got U.S. cover for his rightism; the Philippines and South Korea received some military muscle; and Malaysia’s leaders gained prestige from hobnobbing with Obama. Beijing seems quite content to let all this play out. State media predictably lashed out at Obama’s pledge on the Senkaku/Diaoyu islets and had some stern words on the U.S.-Philippines military agreement. But the official response to Pivot 2.0 was uncharacteristically measured, almost dismissive. When asked about Obama’s visit at a regular press conference Monday, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang said, “Whether it [was] to counter China or not, we will tell based on what the U.S. says and does.” As for China not being on the itinerary, Qin riffed on a saying that traces back to a Qing-era love poem: “You come or you don’t come, I’m right here.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Emily Rauhala / Beijing at emily_rauhala@timeasia.com