On a cold January night, I was making dinner while my three boys played in and around the kitchen. I heard my husband Mark’s key in the lock. Jake and Matthew, my two older sons, tore down the long, narrow hall toward the door. “Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!” they cried and flung themselves at Mark before he was all the way inside.

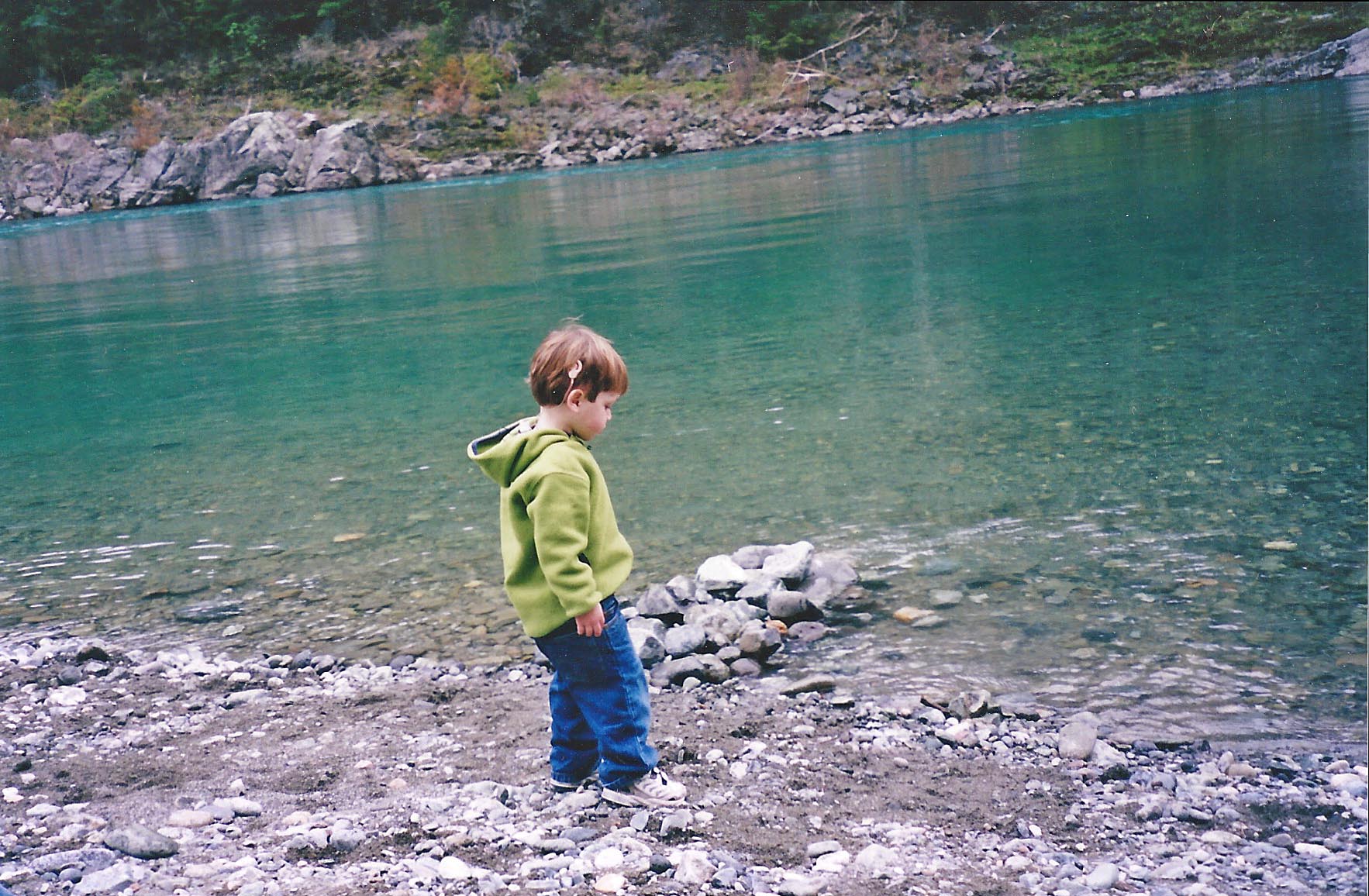

I turned and looked at Alex, my baby, who was 20 months old. He was still sitting on the kitchen floor, his back to the door, fully engaged in rolling a toy truck into a tower of blocks. A raw, sharp ache hit my gut. Taking a deep breath, I bent down, tapped Alex on the shoulder and, when he looked up, pointed at the pandemonium down the hall. His gaze followed my finger. When he spotted Mark, he leapt up and raced into his arms.

He was nearly two and he could say only 'Mama,' 'Dada,' 'hello,' and 'up.'

We had been worried about Alex for months. The day after he was born, four weeks early, in April 2003, a nurse appeared at my hospital bedside. I remember her blue scrubs and her bun and that, when she came in, I was watching the news reports from Baghdad, where Iraqis were throwing shoes at a statue of Saddam Hussein and people thought we had already won the war. The nurse told me Alex had failed a routine hearing test.

“His ears are full of mucus because he was early,” the nurse explained, “that’s probably all it is.” A few weeks later, when I took Alex back to the audiologist as instructed, he passed a test designed to uncover anything worse than mild hearing loss. Relieved, I put hearing out of my mind.

It wasn’t until that January night in the kitchen that Alex was totally and obviously unresponsive to sound. Within weeks, tests revealed a moderate to profound sensorineural hearing loss in both of Alex’s ears. That meant that the intricate and finely tuned cochleas in Alex’s ears weren’t conveying sound the way they should.

Nonetheless, he still had usable hearing. With hearing aids, there was every reason to think Alex could learn to speak and listen. We decided to make that our goal. He had a lot of catching up to do. He was nearly two and he could say only “Mama,” “Dada,” “hello,” and “up.”

A few months later we got a further unwelcome surprise: All of the hearing in Alex’s right ear was gone. He was now profoundly deaf in that ear. We had discovered in the intervening months that in addition to a congenital deformity of the inner ear called Mondini dysplasia, he had a progressive condition called Enlarged Vestibular Aqueduct (EVA). That meant a bang on the head or even a sudden change in pressure could cause further loss of hearing. It seemed likely to be only a matter of time before the left ear followed the right.

Suddenly Alex was a candidate for a cochlear implant. When we consulted a surgeon, he clipped several CT scan images of our son’s head up on the light board and tapped a file containing reports of Alex’s latest hearing tests and speech/language evaluations, which still put him very near the bottom compared to other children his age: He was in the sixth percentile for what he could understand and the eighth for what he could say.

“He is not getting what he needs from the hearing aids. His language is not developing the way we’d like,” the doctor said. Then he turned and looked directly at us. “We should implant him before he turns three.”

The Cochlear Countdown

A deadline? So there was now a countdown clock to spoken language ticking away in Alex’s head? What would happen when it reached zero? Alex’s third birthday was only a few months away.

As the doctor explained that the age of three marked a critical juncture in the development of language, I began to truly understand that we were not just talking about Alex’s ears. We were talking about his brain.

'Hot damn, I want to take this one home with me,' the patient exclaimed.

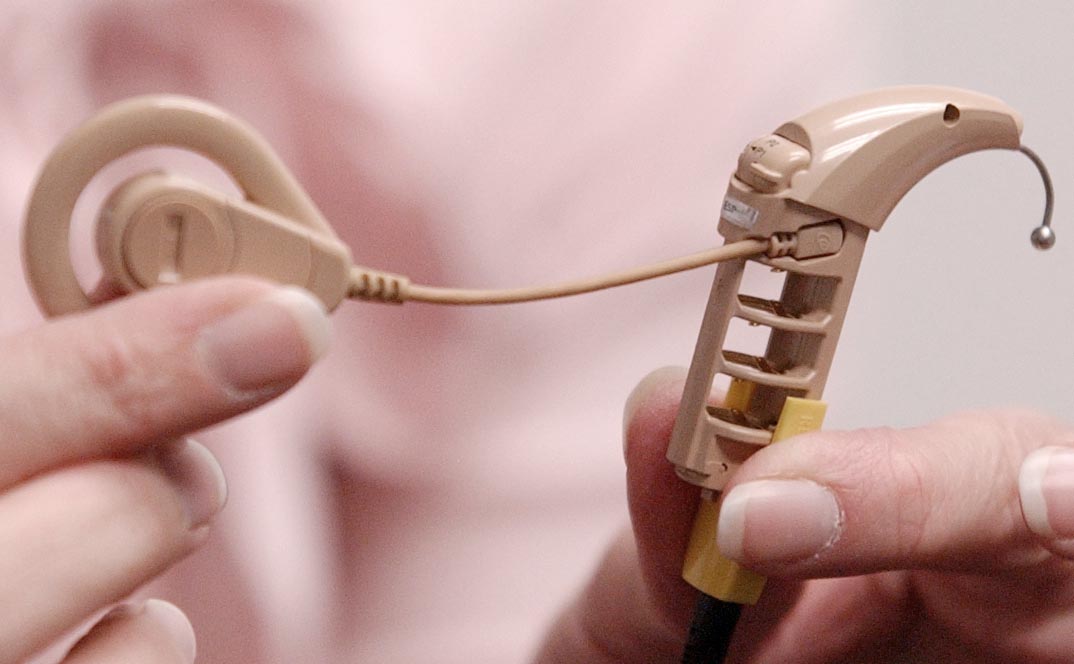

When they were approved for adults in 1984 and children six years later, cochlear implants were the first device to partially restore a missing sense. How could it be possible to hear without a functioning cochlea? The cochlea is the hub, the O’Hare Airport, of normal hearing, where sound arrives, changes form, and travels out again. When acoustic energy is naturally translated into electrical signals, it produces patterns of activity in the 30,000 fibers of the auditory nerve that the brain ultimately interprets as sound. The more complex the sound, the more complex the pattern of activity. Hearing aids depend on the cochlea. They amplify sound and carry it through the ear to the brain, but only if enough functioning hair cells in the cochlea can transmit the sound to the auditory nerve. Most people with profound deafness have lost that capability. The big idea behind a cochlear implant is to fly direct, to bypass a damaged cochlea and deliver sound — in the form of an electrical signal — to the auditory nerve itself.

To do that is like bolting a makeshift cochlea to the head and somehow extending its reach deep inside. A device that replicates the work done by the inner ear and creates electrical hearing instead of acoustic hearing requires three basic elements: a microphone to collect sounds; a package of electronics to process those sounds into electrical signals (a “processor”); and an array of electrodes to conduct the signal to the auditory nerve. The processor has to encode the sound it receives into an electrical message the brain can understand; it has to send instructions. For a long time, no one knew what those instructions should say. They could, frankly, have been in Morse code — an idea some researchers considered, since dots and dashes would be straightforward to program and constituted a language people had proven they could learn. By comparison, capturing the nuance and complexity of spoken language in an artificial set of instructions was like leaping straight from the telegraph to the Internet era.

It was such a daunting task that most of the leading auditory neurophysiologists in the 1960s and 1970s, when the idea was first explored in the United States, were convinced cochlear implants would never work. It took decades of work by teams of determined (even stubborn) researchers in the United States, Australia and Europe to solve the considerable engineering problems involved as well as the thorniest challenge: designing a processing program that worked well enough to allow users to discriminate speech. When they finally succeeded on that front, the difference was plain from the start.

“There are only a few times in a career in science when you get goose bumps,” Michael Dorman, a cochlear implant researcher at Arizona State University, once wrote. That’s what happened to him when, as part of a clinical trial, his patient Max Kennedy tried out the new program, which alternated electrodes and sent signals at a relatively high rate. Kennedy was being run through the usual set of word and sentence recognition tests. “Max’s responses [kept] coming up correct,” remembered Dorman. “Near the end of the test, everyone in the room was staring at the monitor, wondering if Max was going to get 100 percent correct on a difficult test of consonant identification. He came close, and at the end of the test, Max sat back, slapped the table in front of him, and said loudly, “Hot damn, I want to take this one home with me.”

A Cure or a Genocide?

So did I. The device sounded momentous and amazing to me — a common reaction for a hearing person. As Steve Parton, the father of one of the first children to receive an implant once put it, the fact that technology had been invented that could help the deaf hear seemed “a miracle of biblical proportions.”

Many in Deaf culture didn’t agree. As I began to investigate what a cochlear implant would mean for Alex, I spent a lot of time searching the Internet, and reading books and articles. I was disturbed by the depth of the divide I perceived in the deaf and hard of hearing community. There seemed to be a long history of disagreement over spoken versus visual language, and between those who saw deafness as a medical condition and those who saw it as an identity. The harshest words and the bitterest battles had come in the 1990s with the advent of the cochlear implant.

I found cochlear implantation of children described as child abuse.

By the time I was thinking about this, in 2005, children had been receiving cochlear implants in the United States for 15 years. Though the worst of the enmity had died down, I felt as if I’d entered a city under ceasefire, where the inhabitants had put down their weapons but the unease was still palpable. A few years earlier, the National Association of the Deaf, for instance, had adjusted its official position on cochlear implants to very qualified support of the device as one choice among many. It wasn’t hard, however, to find the earlier version, in which they “deplored” the decision of hearing parents to implant their children. In other reports about the controversy, I found cochlear implantation of children described as “child abuse.”

No doubt those quotes had made it into the press coverage precisely because they were extreme and, therefore, attention-getting. But child abuse?! I just wanted to help my son. What charged waters were we wading into?

Cochlear implants arrived in the world just as the Deaf Civil Rights movement was flourishing. Like many minorities, the deaf had long found comfort in each other. They knew they had a “way of doing things” and that there was what they called a “deaf world.” Largely invisible to hearing people, it was a place where many average deaf people lived contented, fulfilling lives. No one had ever tried to name that world.

Beginning in the 1980s, however, deaf people, particularly in academia and the arts, “became more self-conscious, more deliberate, and more animated, in order to take their place on a larger, more public stage,” wrote Carol Padden and Tom Humphries, professors of communication at the University of California, San Diego, who are both deaf. They called that world Deaf culture in their influential 1988 book Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture. The capital “D” distinguished those who were culturally deaf from those who were audiologically deaf. “The traditional way of writing about Deaf people is to focus on the fact of their condition — that they do not hear — and to interpret all other aspects of their lives as consequences of this fact,” Padden and Humphries wrote. “Our goal . . is to write about Deaf people in a new and different way. . . Thinking about the linguistic richness uncovered in [work on sign language] has made us realize that the language has developed through the generations as part of an equally rich cultural heritage. It is this heritage — the culture of Deaf people — that we want to begin to portray.”

In this new way of thinking, deafness was not a disability but a difference. With new pride and confidence, and new respect for their own language, American Sign Language, the deaf community began to make itself heard. At Gallaudet University in 1988, students rose up to protest the appointment of a hearing president — and won. In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act ushered in new accommodations that made operating in the hearing world far easier. And technological revolutions like the spread of computers and the use of e-mail meant that a deaf person who once might have had to drive an hour to deliver a message to a friend in person (not knowing before setting out if the friend was even home), could now send that message in seconds from a keyboard.

In 1994, Greg Hlibok, one of the student leaders of the Gallaudet protests a few years earlier, declared in a speech: “From the time God made earth until today, this is probably the best time to be Deaf.”

Into the turbulence of nascent deaf civil rights dropped the cochlear implant.

The Food and Drug Administration’s 1990 decision to approve cochlear implants for children as young as two galvanized Deaf culture advocates. They saw the prostheses as just another in a long line of medical fixes for deafness. None of the previous ideas had worked, and it wasn’t hard to find doctors and scientists who maintained that this wouldn’t work either — at least not well. Beyond the complaint that the potential benefits of implants were dubious and unproven, the Deaf community objected to the very premise that deaf people needed to be fixed at all. “I was upset,” Ted Supalla, a linguist who studies ASL at Georgetown University Medical Center, told me. “I never saw myself as deficient ever. The medical community was not able to see that we could possibly see ourselves as perfectly fine and normal just living our lives. To go so far as to put something technical in our brains, at the beginning, was a serious affront.”

The Deaf view was that late-deafened adults were old enough to understand their choice, had not grown up in Deaf culture, and already had spoken language. Young children who had been born deaf were different. The assumption was that cochlear implants would remove children from the Deaf world, thereby threatening the survival of that world. That led to complaints about “genocide” and the eradication of a minority group. The Deaf community felt ignored by the medical and scientific supporters of cochlear implants; many believed deaf children should have the opportunity to make the choice for themselves once they were old enough; still others felt the implant should be outlawed entirely. Tellingly, the ASL sign developed for “cochlear implant” was two fingers stabbed into the neck, vampire-style.

The medical community agreed that the stakes were different for children. “For kids, of course, what really counts is their language development,” says Richard Dowell, who today heads the University of Melbourne’s Department of Audiology and Speech Pathology but in the 1970s was part of an Australian team led by Graeme Clark that played a critical role in developing the modern-day cochlear implant. “You’re trying to give them good enough hearing to actually then use that to assist their language development as close to normal as possible. So the emphasis changes very, very much when you’re talking about kids.”

Implanted and improving

By the time Alex was born, children were succeeding in developing language with cochlear implants in ever greater numbers. The devices didn’t work perfectly and they didn’t work for everyone, but the benefits could be profound. The access to sound afforded by cochlear implants could serve as a gateway to communication, to spoken language and then to literacy. For hearing children, the ability to break the sound of speech into its components parts — a skill known as phonological awareness — is the foundation for learning to read.

I picked Alex up and hugged him tight. 'You did it,' I said.

We wanted to give Alex a chance to use sound. In December 2005, four months before he turned three, he received a cochlear implant in his right ear and we dug into the hard work of practicing speaking and listening.

One year later, it was time to measure his progress. We went through the now familiar barrage of tests: flip charts of pictures to check his vocabulary (“point to the horse”), games in which Alex had to follow instructions (“put the purple arms on Mr. Potato Head”), exercises in which he had to repeat sentences or describe pictures. The speech pathologist would assess his understanding, his intelligibility, his general language development.

To avoid prolonging the suspense, the therapist who did the testing calculated his scores for me before we left the office and scribbled them on a yellow Post-It note. First, she wrote the raw scores, which didn’t mean anything to me. Underneath, she put the percentiles: where Alex fell compared to his same-aged peers. These were the scores that had been so stubbornly dismal the year before when Alex seemed stuck in single-digit percentiles.

Now, after 12 months of using the cochlear implant, the change was almost unbelievable. His expressive language had risen to the 63rd percentile and his receptive language to the 88th percentile. He was actually above age level on some measures. And that was compared to hearing children.

I stared at the Post-It note and then at the therapist.

“Oh my god!” was all I could say. I picked Alex up and hugged him tight.

“You did it,” I said.

Listening to Each Other

I was thrilled with his progress and with the cochlear implant. But I still wanted to reconcile my view of this technology with that of Deaf culture. Since those nights early on when I was trolling the Internet for information on hearing loss, Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., had loomed large as the center of Deaf culture, with what I presumed would be a correspondingly large number of cochlear implant haters. By the time I visited the campus in 2012, I no longer imagined I would be turned back at the front gates, but just the year before a survey had shown that only one-third of the student body believed hearing parents should be permitted to choose cochlear implants for their deaf children.

“About fifteen years ago, during a panel discussion on cochlear implants, I raised this idea that in ten to fifteen years, Gallaudet is going to look different,” says Stephen Weiner, the university’s provost. “There was a lot of resistance. Now, especially the new generation, they don’t care anymore.” ASL is still the language of campus and presumably always will be, but Gallaudet does look different. The number of students with cochlear implants stands at 10 percent of undergraduates and 7 percent overall. In addition to more cochlear implants, there are more hearing students, mostly enrolled in graduate programs for interpreting and audiology.

Only one-third of the student body believed hearing parents should be permitted to choose cochlear implants for their deaf children.

“I want deaf students here to see everyone as their peers, whether they have a cochlear implant or are hard of hearing, can talk or can’t talk. I have friends who are oral. I have one rule: We’re not going to try to convert one another. We’re going to work together to improve the life of our people. The word ‘our’ is important. That’s what this place will be and must be. Otherwise, why bother?” Not everyone agrees with him, but Weiner enjoys the diversity of opinions.

At the end of our visit, he hopped up to shake my hand.

“I really want to thank you again for taking time to meet with me and making me feel so welcome,” I said.

“There are people here who were nervous about me talking to you,” he admitted. “I think it’s important to talk.”

So I made a confession of my own. “I was nervous about coming to Gallaudet as the parent of a child with a cochlear implant,” I said. “I didn’t know how I’d be treated.”

He smiled, reached up above his right ear, and flipped the coil of a cochlear implant off his head. I hadn’t realized it was there, hidden in his brown hair. Our entire conversation had been through an interpreter. He seemed pleased that he had managed to surprise me.

“I was one of the first culturally Deaf people to get one.”

Perhaps it’s not surprising that most of the people who talked to me at Gallaudet turned out to have a relatively favorable view of cochlear implants. When I met Irene Leigh, she was about to retire as chair of the psychology department after more than 20 years there. She doesn’t have an implant, but is among the Gallaudet professors who have devoted the most time to thinking about them.

She and sociology professor John Christiansen teamed up in the late 1990s to (gingerly) write a book about parent perspectives on cochlear implants for children; it was published in 2002. At that time, she says, “A good number of the parents labeled the Deaf community as being misinformed about the merits of cochlear implants and not understanding or respecting the parents’ perspective.” For their part, the Deaf community at Gallaudet was beginning to get used to the idea by then, but true supporters were few and far between.

In 2011, Leigh served as an editor with Raylene Paludneviciene of a follow-up book examining how perspectives had evolved. Culturally Deaf adults who had received implants were no longer viewed as automatic traitors, they wrote. Opposition to pediatric implants was “gradually giving way to a more nuanced view.” The new emphasis on bilingualism and biculturalism, says Leigh, is not so much a change as a continuing fight for validation. The goal of most in the community is to establish a path that allows implant users to still enjoy a Deaf identity. Leigh echoes the inclusive view of Steve Weiner when she says, “There are many ways of being deaf.”

Ted Supalla, the ASL scholar who was so upset by cochlear implants, had deaf parents and deaf brothers, a background that makes him “deaf of deaf” and accords him elite status in Deaf culture. Yet when we met, he had recently left the University of Rochester after many years there to move to Washington D.C. with his wife, the neuroscientist Elissa Newport. They were setting up a new lab not at Gallaudet but at Georgetown University Medical Center. Waving his hand out the window at the hospital buildings, Supalla acknowledged the unexpectedness of his new surroundings. “It’s odd that I find myself working in a medical community . . . It’s a real indication that times are different now.”

‘Deaf like me’

Alex will never experience deafness in quite the same way Ted Supalla does. And neither do the many deaf adults and children — some 320,000 of them worldwide — who have embraced cochlear implants gratefully.

But they are all still deaf. Alex operated more and more fluently in the hearing world as he got older, yet when he took off his processor and hearing aid, he could no longer hear me unless I spoke loudly within inches of his left ear.

I never wanted us not to be able to communicate. Even if Alex might never need ASL, he might like to know it. And he might someday feel a need to know more deaf people. In the beginning, we had said that Alex would learn ASL, as a second language. And we’d meant it — in a vague, well-intentioned way.

We had said that Alex would still learn ASL — and we’d meant it, in a vague way.

Though I used a handful of signs with him in the first few months, those had fallen away once he started to talk. I regretted letting sign language lapse. The year Alex was in kindergarten, an ASL tutor named Roni began coming to the house. She, too, was deaf and communicated only in ASL.

Through no fault of Roni’s, those lessons didn’t go so well. It was striking just how difficult it was for my three boys, who were then five, seven and 10, to pay visual attention, to adjust to the way of interacting that was required in order to sign. (Rule number one is to make eye contact.) Even Alex behaved like a thoroughly hearing child. It didn’t help that our lessons were at seven o’clock at night and the boys were tired. I spent more time each session reining them in than learning to sign. The low point came one night when Alex persisted in hanging upside down and backward off an armchair.

“I can see her,” he insisted.

And yet he was curious about the language. I could tell from the way he played with it between lessons. He decided to create his own version, which seemed to consist of opposite signs: YES was NO and so forth. After trying and failing to steer him right, I concluded that maybe experimenting with signs was a step in the right direction.

Even though we didn’t get all that far that spring, there were other benefits. At the last session, after I had resolved that one big group lesson in the evening was not the way to go, Alex did his usual clowning around and refusing to pay attention. But when it was time for Roni to leave, he gave her a powerful hug that surprised all of us.

“She’s deaf like me,” he announced.

Lydia Denworth is the author or I Can Hear You Whisper: An Intimate Journey through the Science of Sound and Language (Dutton), from which this piece is adapted.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com