Photographer Bill Henson has always been obsessed with the physical process of making art. Growing up in suburban Melbourne, Australia, Henson began his career as a painter inspired by etchings of Rembrandt. His first solo exhibition of photography, when he was 19, was held at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1975.

“I love making objects and they just so happen to be photographs,” Henson says. “The starting point for me is the primal reaction that our bodies have to the things around us” — in this case, the photographic object. Henson meticulously prints all of his own work and still mostly shoots on film for the endless depth of tone he finds in it.

In this week’s issue of TIME, Henson collaborated with actress Cate Blanchett for a story about her role in Blue Jasmine, the latest film by Woody Allen. She plays a troubled woman who—forced by financial crisis—leaves her lofty New York home to live with her sister in San Francisco. Henson’s portrait captures a vulnerable and introspective Blanchette.

When asked about photographing her for the first time, Henson aimed for the unfamiliar. “With Cate, I’m almost making an anti-portrait. I want to retain the distinct qualities of the person but I also want to universalize the portrayal. I’m interested in producing something which is intensely intimate rather than something that is merely familiar.”

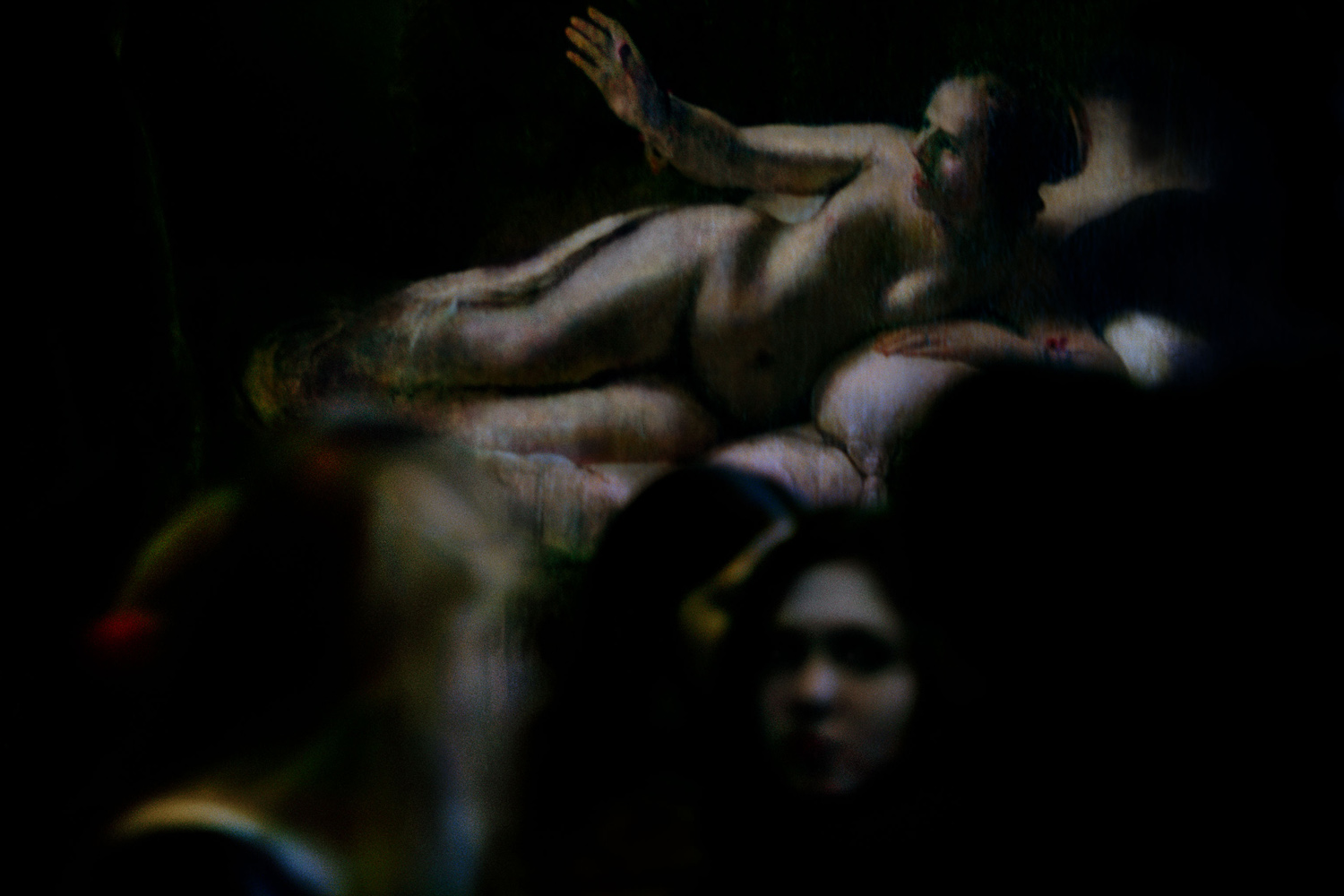

Henson’s work continually refines a narrative on the fleeting transience of youth and nature. In his series Paris Opera (1990-1991), he focused on young girls on the cusp of adulthood, lighting them subtlety by the glow of the stage. And in his now rare book Lux et Nox (Scalo 2002 and 2009), his subjects are adrift in blackness—floating and perpetually longing on the outskirts of what feels like suburban wasteland. The work is suggestive of a classically romantic ideal of youth and is filled with a sense of endless potential and longing.

Says Henson: “New images grow out of old images. It’s cumulative and really I can’t tell you where it’s going.”

He uses darkness to isolate his subjects, building on a narrative that runs throughout his work since his earliest days as an artist. “What can be most important”, Henson explains to TIME, “is what goes missing in the shadows rather than what’s clearly defined. For example, I can take a picture of a road winding off into the darkness, but when the image really absorbs your attention it becomes your road.”

In his recent Untitled series, figure studies are set against total blackness and juxtaposed with landscapes of mountains and water, evoking encounters with the sublime.

A turned head or the slightest twist of a body in the darkness can look like classical sculpture and feel even more monumental. “I’m trying to produce an image when the figure has all this potentiality,” he says. “When you’re photographing a kid and they turn their head, you almost want it to feel like the great pyramids. You’re looking for an intensely intimate, breezing, proximate presence but, at the same time, something that is millennially distant.”

Henson’s sessions with his subjects is a process that unfolds over many hours. “You want to slow everything down until it becomes almost mesmeric.” The intense concentration over such a long period immerses his subjects in the process. “You don’t want people to act,” he says. “You just want them to be.”

Bill Henson is represented by the Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne, Australia and by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney. You can see more of his work here.

Paul Moakley is the Deputy Photo Editor at TIME. You can follow him on Twitter at @paulmoakley.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com