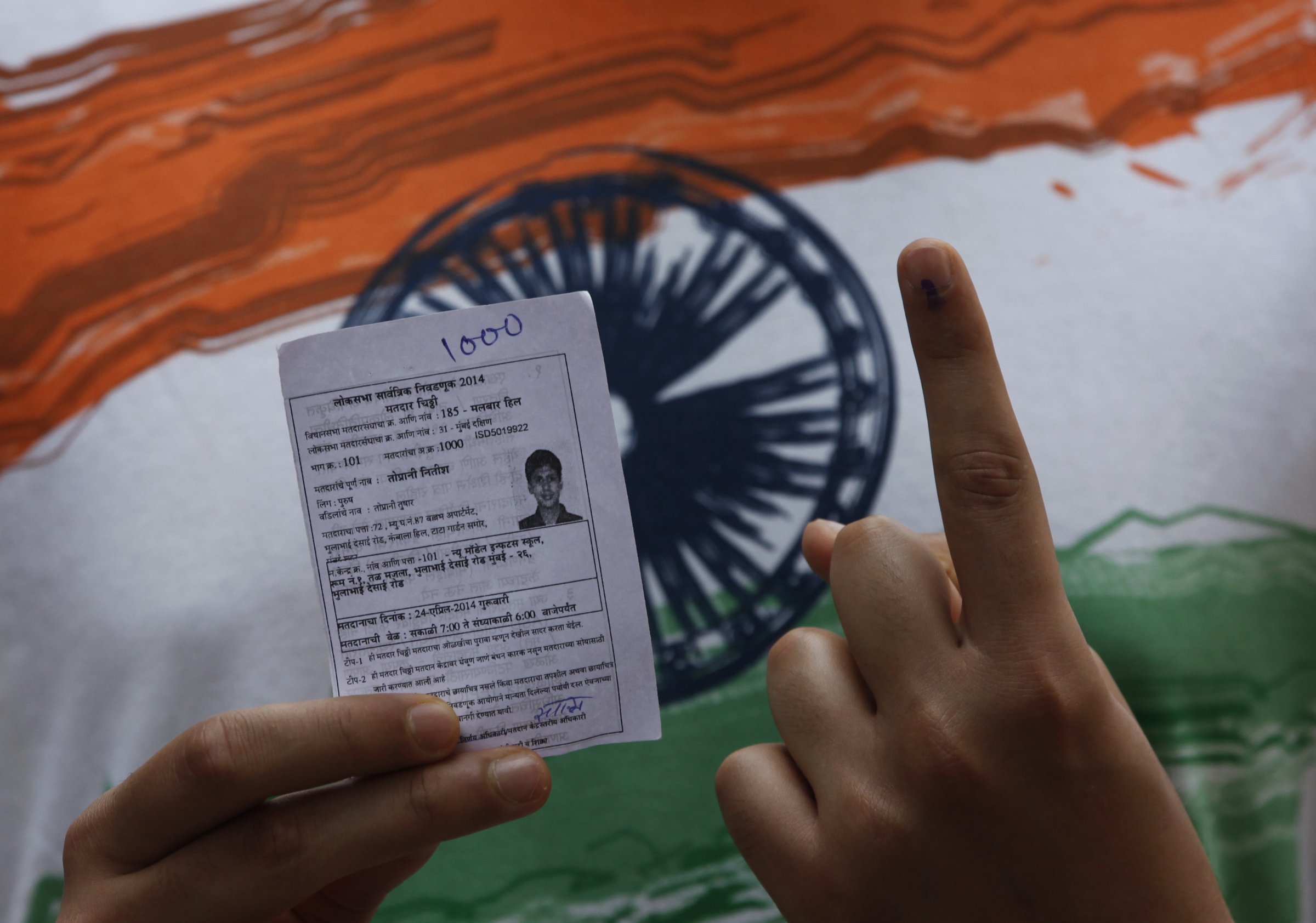

Rachna Kedia knocks on her neighbor’s front door in an apartment building in Malabar Hill, a posh enclave in south Mumbai. A man opens and raises his eyebrows in mock alarm. “I’m going! I’m going!” he says. “What about the rest of the family?” Kedia asks. One by one, family members appear to assure the representative of Volunteer for a Better India (VBI) — an NGO promoting volunteerism — that they will be voting on April 24. “Obviously,” says another woman downstairs. “It’s our right, and we’re going to do it.”

As it turned out, only a slim majority of residents of India’s frenetic and charismatic financial capital broke out of their normally apathetic shell on Thursday and turned up to vote on a sweltering day. Early estimates of voter turnout across the city was about 52%, according to local reports.

That’s over 11% higher than the last national elections in 2009, but it still means that almost half of the voters in this city of 12 million shunned the polling booths. In recent months, volunteers like Kedia have been fanning out around town to try to turn Mumbai’s voting numbers around. “A lot of awareness has happened, but a lot still needs to happen,” she says. In the run-up to the vote, organizations like VBI (an offshoot of the Art of Living Foundation), India First, a local grassroots group, and the IndiaVoting Coalition focused on getting out the vote of corporate workers nationally. They also joined up with political parties to help register voters and encouraged them to show up at the polls.

Companies like Reliance and ICICI bank participated in drives to get their employees to the polls too. Hitesh Barot, who heads the IndiaVoting Coalition, says that with parties focused on courting votes in traditional vote banks like slums, legions of corporate employees in cities like Mumbai were left out of the registration drive. “White collar Indians have not been viewed as a voting block and are left to fend for themselves.”

Even if Mumbai’s turnout was low compared with other parts of the country, the intense national interest in this election helped beat 2009’s anemic numbers. The closely watched showdown between the incumbent Congress Party and the main opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which in Mumbai is partnered with the powerful local party Shiv Sena, has captivated people around the country.

It’s too soon to say what that means for the candidates duking it out for the city’s six seats in Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of Parliament. (Results are expected on May 16.) In 2009, riding the wave of high economic growth at the time, the incumbent Congress Party swept the polls. This year the verdict is less certain. Muslims, who make up some 20% of eligible voters, according to the State Minorities Commission, may be galvanized to defeat the BJP’s prime-ministerial candidate Narendra Modi, who was chief minister of the western state of Gujarat during a 2002 wave of religious riots in which over 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed.

In Dharavi, a slum in south Mumbai, Ansar Khan, a Muslim tailor, says that recent anti-Muslim comments from the BJP’s associates have made him freshly apprehensive about a BJP-led government in New Delhi. “The Muslim community does not vote in a block, but when you hear these speeches, what am I supposed to think?” asks Khan, 52, referring to alleged comments by Hindu-nationalist leader Pravin Togadia on driving Muslims out of Hindu neighborhoods. “Aren’t we supposed to be worried?”

BJP–Shiv Sena supporters meanwhile say a bigger turnout in Mumbai is a clear demonstration of people’s weariness of Congress, which has been in power nationally since 2004. In Banganga, a narrow, winding neighborhood on Malabar Hill, Mihika Ronish and her brother have just voted for the first time because, she says, they are fed up. “I think Congress has literally made India hit rock bottom,” Ronish, 27, said on voting day. She cast her vote with the BJP-Sena alliance, as has her brother, mother and father, who all came to vote together. “I know so many people who are going and voting for the first time today,” she says.

Yesterday’s vote was not without incident. Local media reported that thousands of voters were left off the voter lists at polling stations, unable to vote. In the past four years, election officials’ efforts to clean up the rosters have led to the deletion of hundreds of thousands of voters who were identified as dead, relocated or otherwise wrongly listed in their polling district. Despite officials ongoing efforts to inform voters about the deletions by radio and newspaper, many were caught off guard. “Nobody bothered to see whether their name was deleted,” says Maya Patole, an election official in south Mumbai. “Now suddenly they’re saying, ‘My name is not there.’”

But millions more have simply slipped through the cracks. Yesterday’s turnout was still low compared with other parts of the country, where turnout has been over 70%. On a busy side street in east Bandra, where hundreds of day laborers gather and wait to get picked up for work, Rupesh Srivas said he was registered but wouldn’t vote. “There is no sense in it,” says the 24-year-old mason. “If someone was thinking about our future, it would make sense for me to vote. But nobody is thinking about us, so what’s the point?”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com