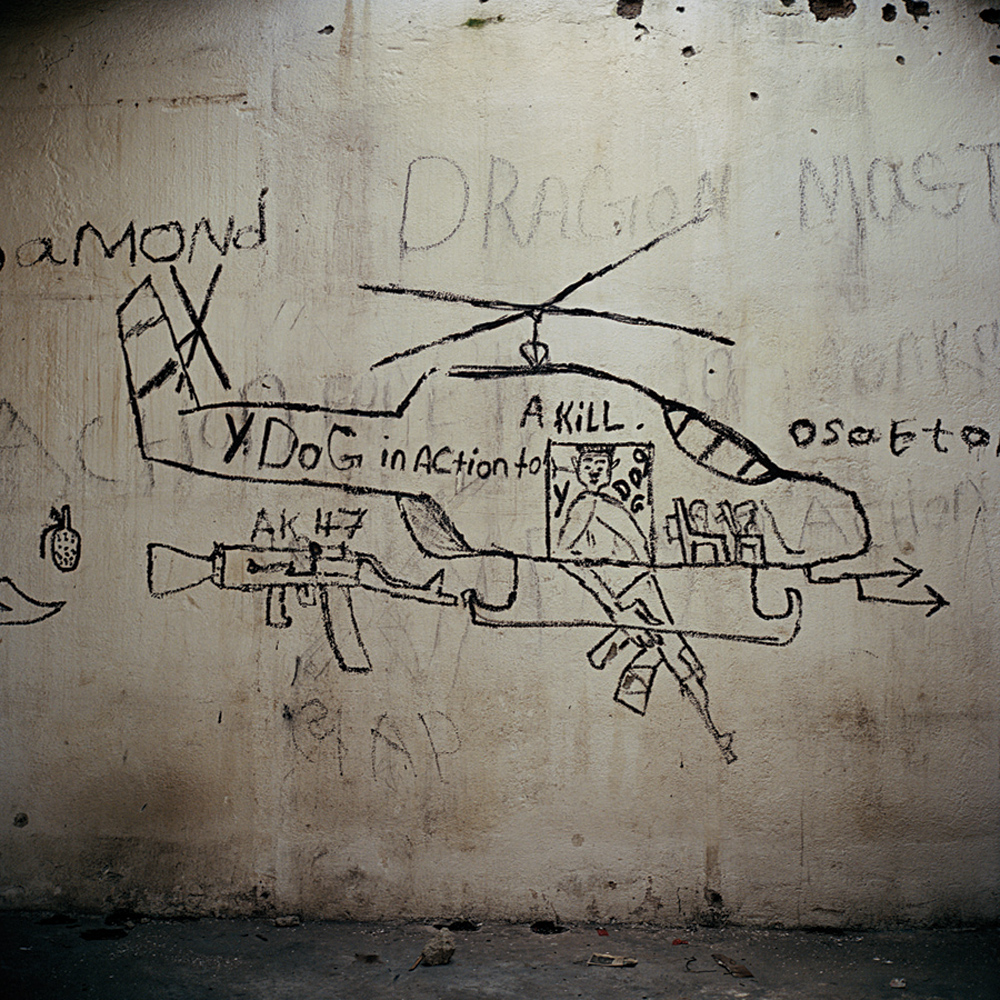

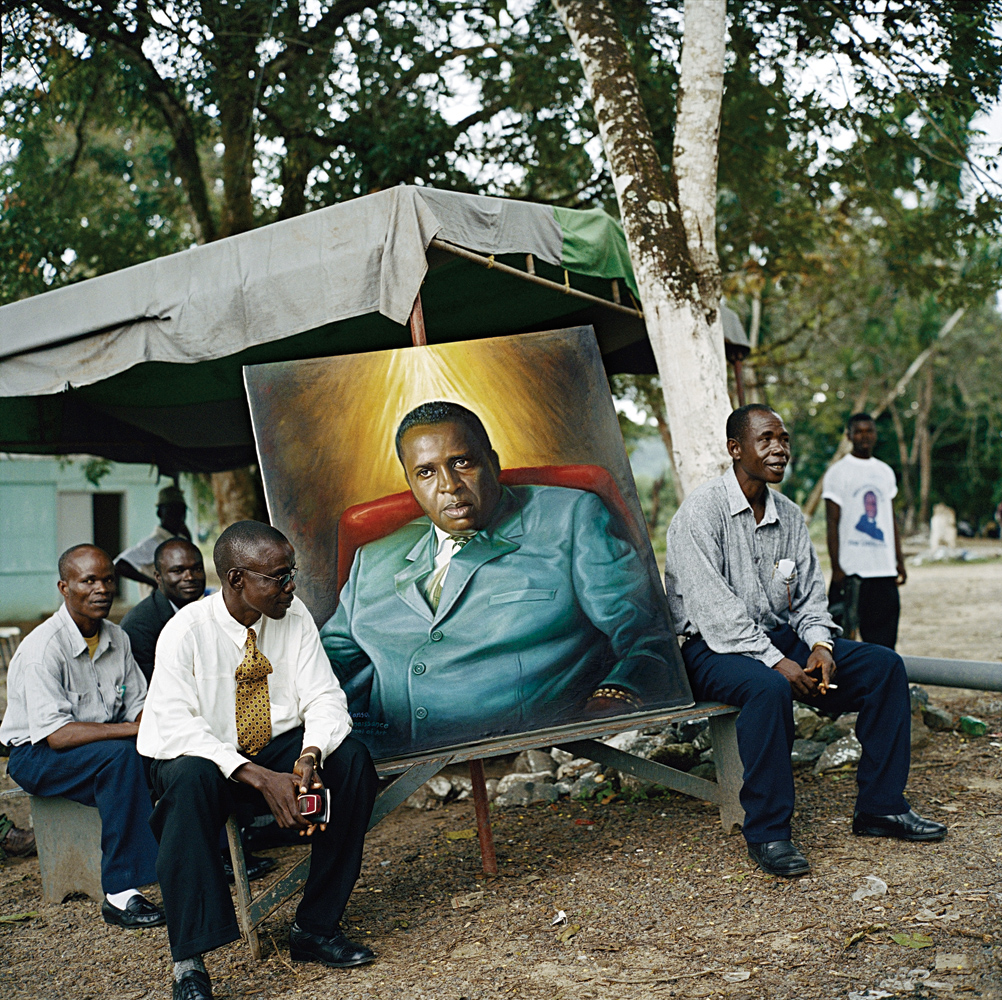

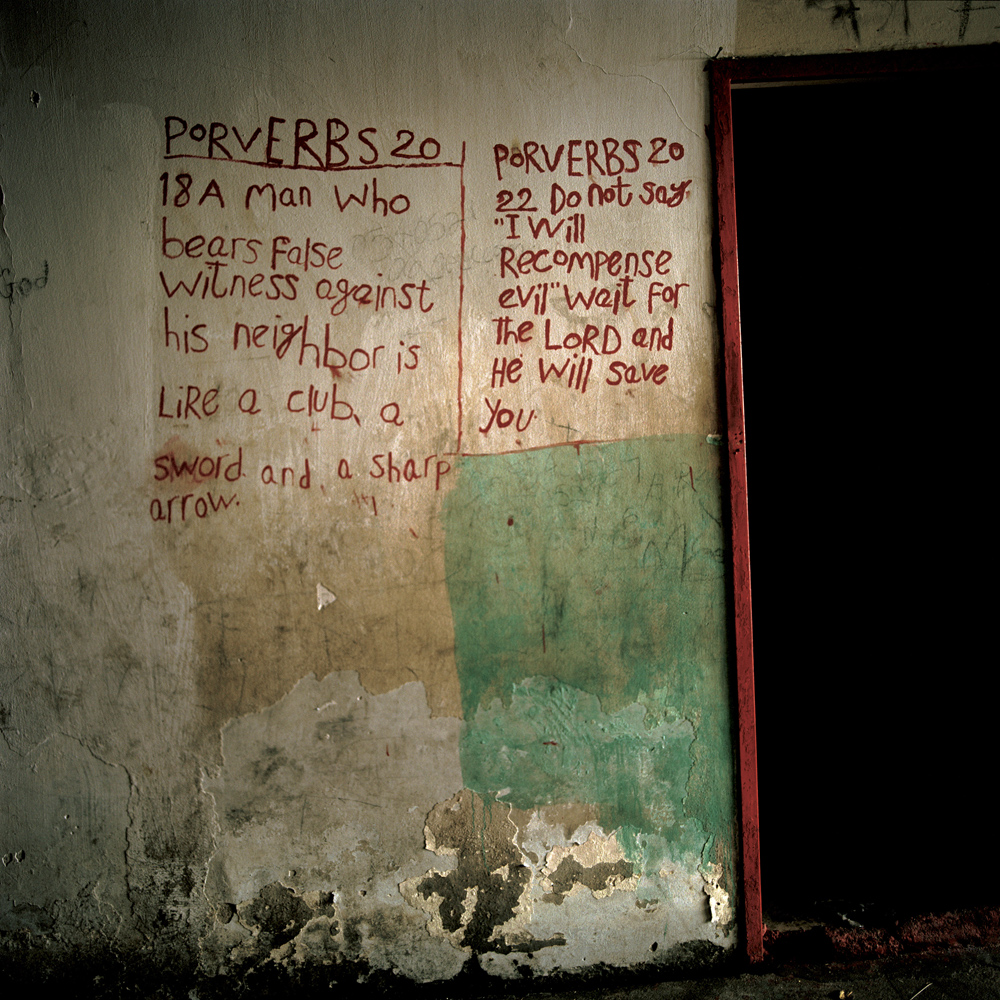

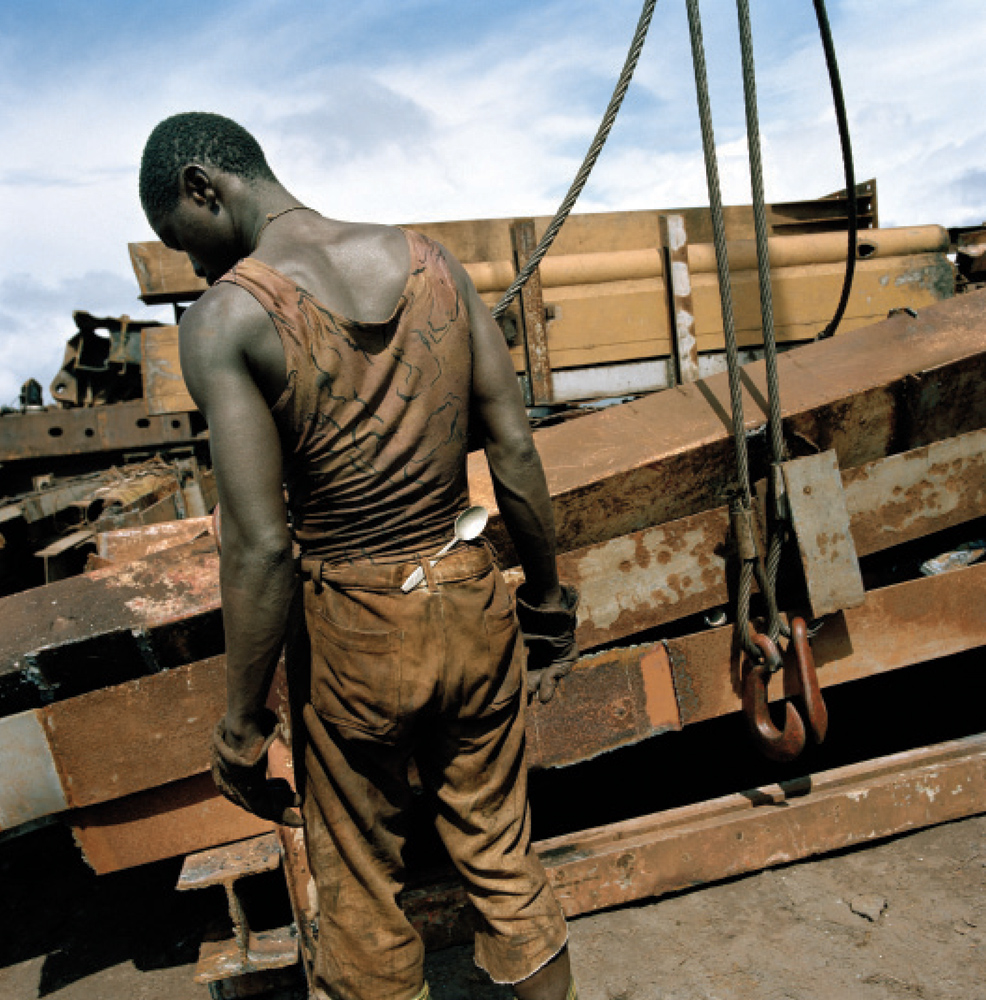

Although Tim Hetherington will best be remembered for his brave, nuanced and sensitive account of the war in Afghanistan, his first book, Long Story Bit By Bit: Liberia Retold, is an overlooked masterpiece. I saw Tim’s work for the first time when I was just discovering photography. I’d been feeding myself with classic frontline imagery — photographs dramatic and powerful, but which often hit me all at once and rarely required further meditation. Tim’s pictures were different. They were taken in the same places, but with a stately sense of quiet and purpose that I initially found confusing. Soon afterward, I moved to South Africa for the year and traveled extensively around the continent documenting similar subjects as Tim. When I returned home, I was frustrated with my photos. Experiences that had been very personal and intimate were visualized as foreign, exotic, clichéd. I revisited Tim’s pictures, and the depth of his vision crystallized. The simple portrait of a thoughtful-looking young man with a still life of a grenade. Two women at the front lines, one carrying a baby on her back and an ammunition canister on her head. A worker loading scrap metal onto a ship, a spoon stuck into his waistband and somehow dominating the frame.

When Tim released Long Story Bit by Bit several years later, I bought it immediately. There are many great books of photography on Africa, but Tim’s is one of the most important. It builds a narrative in pictures and words that discards easy melodramatics in favor of personal stories, a deep knowledge of history, a firm context, emotional honesty and nuance and an overriding sense of compassion. The collective weight of those images comes closest to that most elusive ideal of photography: the other becomes ourselves, a distant and abstract conflict becomes personal and relatable, and the great complexity of our troubled species is laid bare without judgment or pretense.

I last saw Tim a few weeks ago at my birthday party. He was surrounded by friends, Idil clutched close. He had just returned from Libya and was planning to go back. I asked why, and he said he’d “know what to do with it” this time. Important words, coming from him. At the end of the night, I hugged him goodbye and said the usual clichés. “Stay safe, man. Good luck.” We all know the risks, but they simultaneously seemed abstract. Now he’s gone, his ghostly voice floating out of video clips and interviews posted on Facebook by friends mourning his passing. He leaves us his work, a great gift to the historical understanding of some of the critical events of our time. For me, his work also contributes to that more abstract hope: that photographs, words, the collective weight of testimony changes us, makes us better people, gives hope that one distant day, there can be peace. My friend James Pomerantz put it best in describing the passing of Chris Hondros and Tim: “If everyone lived as they lived, nobody would die as they died.”

— Peter Van Agtmael

Peter Van Agtmael is a regular contributor to TIME. He is represented by Magnum Photos and author of 2nd Tour, Hope I Don’t Die.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com