This post is in partnership with Consequence of Sound, an online music publication devoted to the ever growing and always thriving worldwide music scene.

Two summers ago, I was dragged on a date that included a trip to Governor’s Island. For the unfamiliar, that’s the small island between Brooklyn and Manhattan where the Governor’s Ball is held. It didn’t look like there was much to the community, with its constant quietness, the lack of commercial centers, and just how far removed it was — or at least felt like — from regular NYC hustle.

I do credit an otherwise fruitless trip to Governor’s for yielding a first for me. When you travel to the island’s coast at sunset and look outward beyond the island’s parameters, you’ll spot a brown structure freckled with yellowish lights emanating from the project windows rising against the sunset. I was looking at Queensbridge.

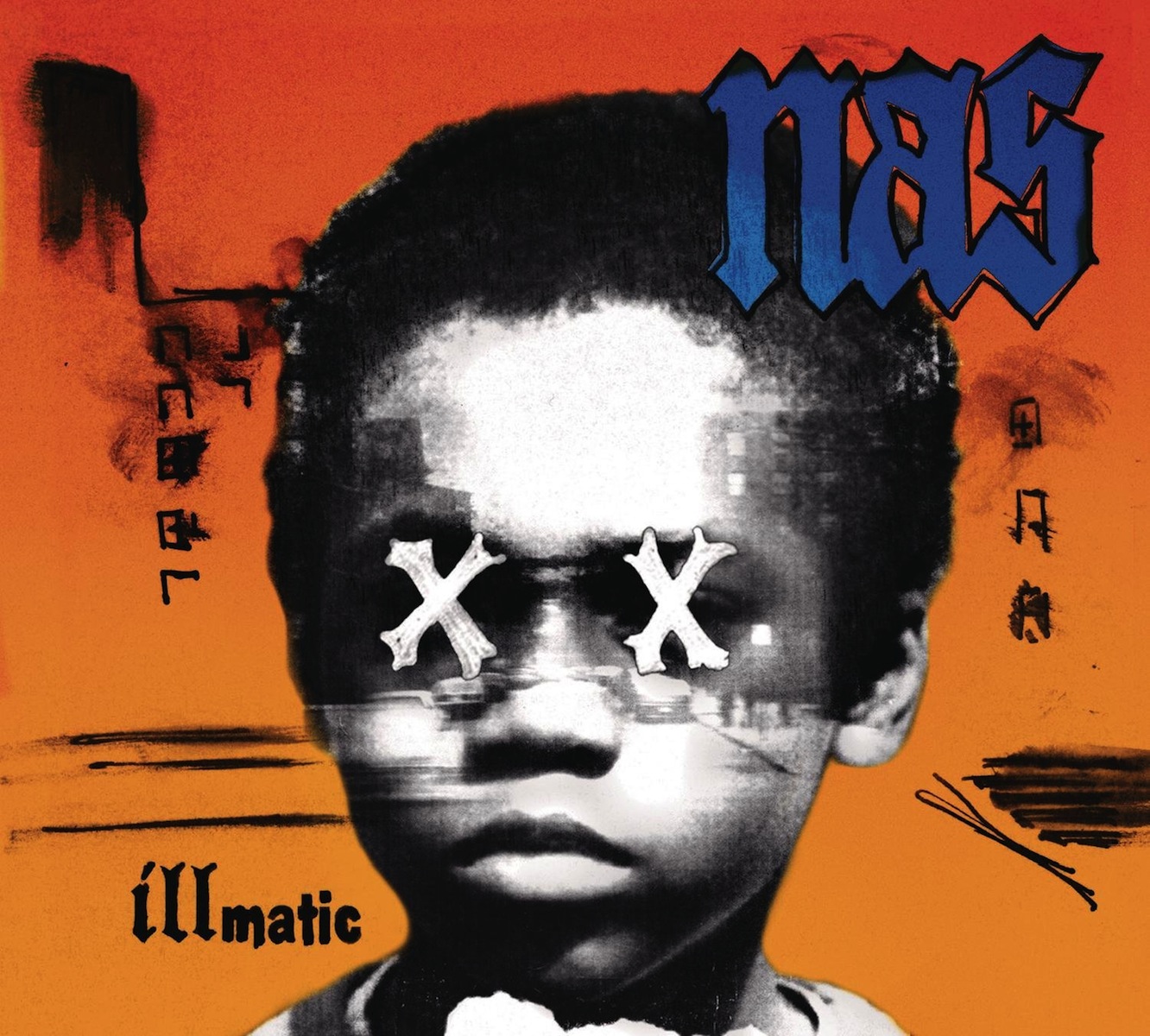

A place of hip-hop reverence was right before my eyes, and the only thing I could think about is how distant it felt. It wasn’t about how I couldn’t quite picture it as the place where Jerome’s niece got popped, Nas once mused at the baseheads, or young men turned into shooters with the dimming hopes of being much of anything beyond the brown labyrinth. Some things never change. Queensbridge Houses is still the largest housing project in North America, where violence is a persistent reality. But at the same time, 2014 New York is very different from 1994. Millennials will never be able to 100 percent relate to Nas’s struggle, but the concept of The Struggle is a very human one that echoes from the Westchester suburbs and Brooklyn’s Flatbush corners. That’s what Nas eloquently and fluidly speaks to throughout Illmatic – a masterpiece that balances self-determinism with the harsh reality of simply staying alive to see a tomorrow whose worth is repeatedly in question.

It’s been written about time and time again. About how Nas was touted as the most prodigious MC New York had to offer and met that large amount of hype. About how Nas evoked Queensbridge’s voicelessness through poetry that was vivid and lurid, thrilling yet introspective, and dark with glimmers of hope. Beyond-his-years self-awareness aside, he may have not been too different from the youths around the way. He and his crew are an inch away from knocking heads in DJ Premier-produced highlight “Represent”, and he talks his shit masterfully on the Michael Jackson-sampling closer, “It Ain’t Hard to Tell”. Nas is a rebel on a street corner, and he’s still in a way trapped by youthful raucousness.

But it is what it is for the most part. A child with the same hardened, deep black eyes spoke on the circumstances of the projects in one Illmatic promo video: “Everybody make money out here. Everybody getting arrested, shot at, beat up. I’m just doing my own thing.”

You never know who that kid comes up to be — if he’s one of the many voiceless youths Nas represents. It’s been said that one of the worst entrapments of the world is being unable to articulate one’s thoughts, and what haunts Illmatic is the sense that Nas could’ve been just a face lost amongst the thousands in the city’s housing projects — maybe even just a memory by now.

It’s an idea that explains some of the pure intensity of the details. The urgency of not knowing how to start this shit on “NY State of Mind” only puts Nas on a higher plane. He takes us through a helter-skelter journey that includes a shootout, heart-stopping threats (“Give me a Smith & Wesson/ I have niggas undressin’”), and self-compliments (“The smooth criminal on beat breaks/ Never put me in your box if your shit eats tapes”). Combined with the nefarious bass line, “NY State of Mind” is epochal even without the context.

Whether it’s kismet or the producers were just really on point during the sessions, Nas even sounds good on the beats on a purely musical level. He sounds just as fluent when he’s happy to be alive at 20 over the R&B grooves on “Life’s a Bitch” (which features a sorrowful trumpet solo from Nas’s father, Olu Dara, on the outro), giving some inspiration on “The World Is Yours”, or floating over that Michael Jackson sample on “It Ain’t Hard to Tell”. It’s as if there’s a conscious attempt at placing Illmatic as canon in the narrative of struggle in black art forms. The almost hymnal chants at the core of “The World Is Yours” and “One Love” give the tracks a sense of mysticism — reaching to form some sort of kinship through what’s unknown outside the Queensbridge streets. It’s both wondrous and heartbreaking, especially in “One Love”. Near the end of his letter to his incarcerated comrades, Nas recounts a meeting with a hardened 12-year-old at a park bench. The kid is already paranoid about killers: “Shorty’s laugh was cold-blooded as he spoke so foul.” Brutal, but kinship is a broken concept in this reality.

As perfect as Illmatic is, there are plenty of crevices that can be explored and different musical avenues to test Nas’s verses/scriptures. Illmatic XX isn’t too special when compared to previous reissues, sans the inclusion of “I’m a Villain” (which features lyrics that are reused throughout the album) and Nas and crew’s 1993 appearance on “The Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito Show”.

As you’d expect, the remixes here don’t add to the original versions as much as they merely provide an alternate vision of them. Part of the reason is how the original cuts have etched themselves into the hip-hop ethos; fans will naturally have a Pavlovian preference toward them. Another reason is that they contort the scope of the original material. The mid-tempo “LG Main Mix” of “One Love” uses what sounds like a chorus of vocals instead of Q-Tip’s nasally croon, and as a result, the highlight becomes a more “Kumbaya”, all-encompassing affair rather than a personal heart-to-heart. Listeners would understandably be more inclined to return to Q-Tip’s version because of how deeply personal Nas feels on the track. The “One L Main Mix” adds a bass line and jangly keys for extra menace, which is unnecessary for a song about reaching through walls for human connection. Getting guitars instead of the “Human Nature” coos on the two “It Ain’t Hard to Tell” mixes are jarring changes, too.

They’re not bad remixes on their own, but they’re ultimately supplemental and inessential. That said, it may be hypocritical to completely dismiss them in the reissue of an album whose acclaim is based off its stunning perspective. A hip-hop perspective that incorporates hard knock realities with that much brutality and beauty hasn’t been seen since. No, not even in the glimpse from Governor’s.

Essential Tracks: “One Love”, “NY State of Mind”, and “It Ain’t Hard to Tell”

More from Consequence of Sound: Here are St. Vincent’s Favorite Songs

More from Consequence of Sound: OutKast’s Top 10 Songs

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com