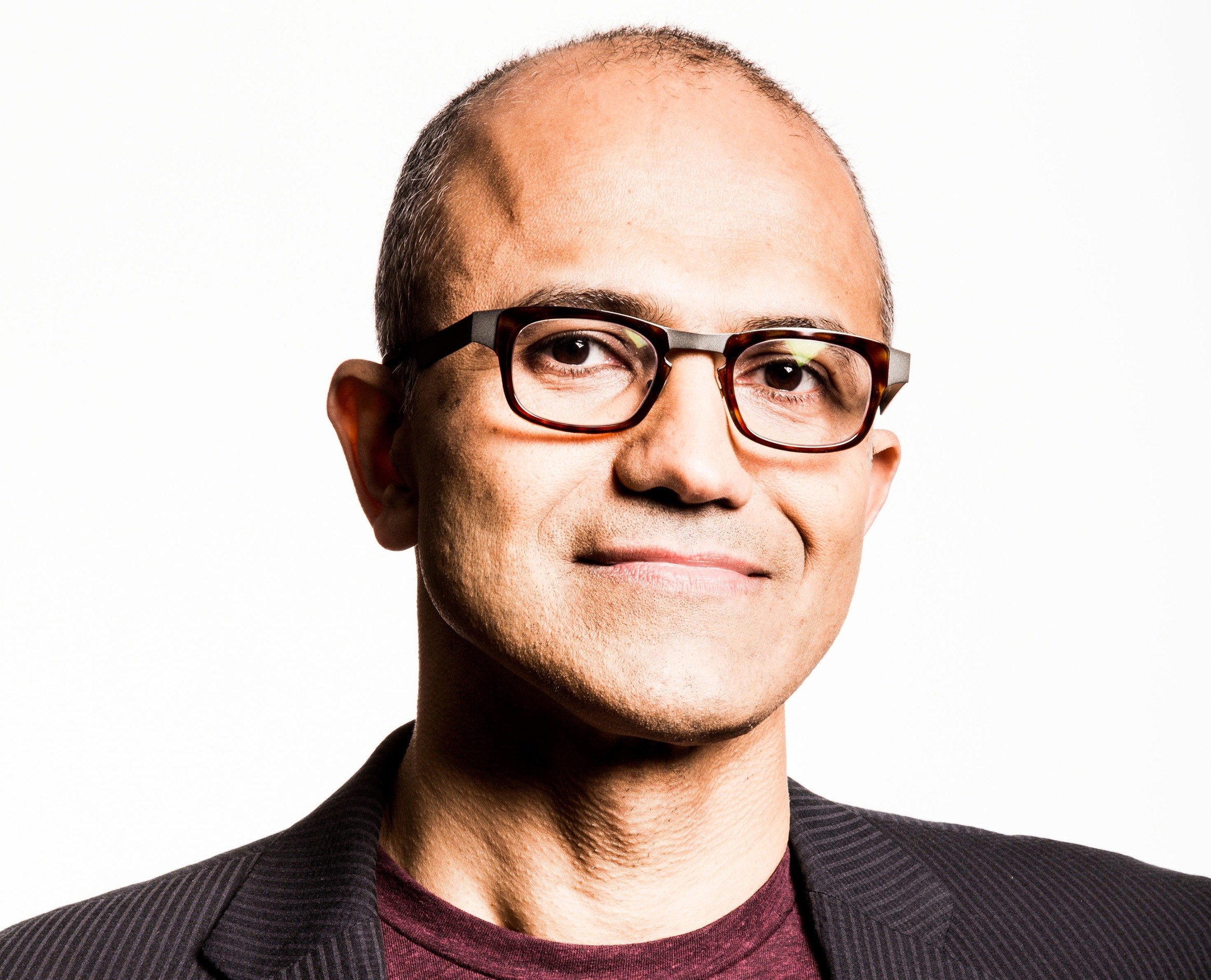

Like many prominent Indians in America today, Satya Nadella, the new chief executive of software giant Microsoft, is one of the “Twice Blessed.” The term was coined by academic Vijay Prashad to describe a generation of Indians who benefited from two of the greatest social movements of the twentieth century: India’s successful fight for Independence from British rule and the civil rights victory in America.

(MORE: Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella Marks Another Victory for Indian Americans)

In many ways, Nadella is a poster child of the Twice Blessed. He was born in 1967, just two years after the passing of the now largely forgotten Hart-Celler Act into law. The Act, which came on the heels of the Civil Rights Act victory, did away with hostile and discriminatory policies toward Asian immigration. Before Hart-Celler, only 100 Indians were allowed into the United States each year and getting Permanent Residency — the coveted Green Card, which is no longer green but remains a rite of passage for every immigrant today — was next to impossible.

My own father discovered just that when he came in 1958 to study for a graduate degree in botany at Princeton University. After doing his post-doctoral work at Harvard, he left for Malaysia because he couldn’t see a clear path to living permanently in America. All that changed with the landmark immigration legislation of 1965. Going forward, immigrants would be allowed into America based on their skills and not just their countries of origin, race and ancestry. In 1970, my father returned to United States with me and my mother in tow.

(MORE: 10 Things to Know About Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s New CEO)

Around the same time, a number of Indians who would play starring roles in American society over the next several decades started washing up on U.S. shores. One was Rajat Kumar Gupta, who until his recent conviction on insider trading charges, was among the most revered Indians in the United States. Gupta came in 1971 on a scholarship to study at Harvard Business School. It was his first step in an astonishing climb up the ladder of white-shoe consulting firm McKinsey & Co., which he headed for an unprecedented three terms.

Several years later, Vikram Pandit, who would one day go on to head banking giant Citigroup, arrived to study in the United States. So did Indra Nooyi, who would eventually head up drinks company PepsiCo, becoming arguably the most powerful female executive in America today.

Other Indians — not so well known — also came to the U.S. at about this time. While their own success would largely be overlooked, the achievements of their sons and daughters would propel the Indian diaspora to new peaks, making them stars not just in business but in fields such as law and politics.

Preetinder Singh Bharara, the U.S. Attorney for the southern district of New York (whose office prosecuted Gupta in 2012) is the son of Indian immigrant parents, too. He likes to tell the story of his dad’s journey to America. His father left India in 1970 with only “a few dollars in his pocket and a hope in his heart that we would have a better life in this country and that his children might, one day, amount to something in America,” Preet Bharara said at the reception for his swearing in as Manhattan U.S. Attorney in 2009. Jagdish Bharara toiled for decades in obscurity as a doctor but his sons — Preet’s younger brother Vinit sold his online diaper business to Amazon.com for more than half a billion dollars two years ago — would more than make up for his life of anonymity.

Their remarkable rise was common among the scions of Indian immigrants. Sri Srinivasan’s parents moved to the United States shortly after he was born in Chandigarh, India in 1967. Last year, Srinivasan was named a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals, District of Columbia circuit, long considered the most important court in the country. Likewise the Jindals migrated to America from the Indian state of Punjab six months before their son Bobby, whose given name is Piyush, was born in 1971. Today Bobby Jindal is the Republican governor of Louisiana and talked about as a potential presidential candidate for the GOP in 2016.

Some of the Indian diaspora that would make a mark in later years in America — men like Gupta and Nadella — would be Twice Blessed, benefiting from both the relaxation of U.S. immigration laws and the enormous investment that India made in education following Independence. Gupta’s story is familiar; he went to the renowned Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi which was one of a handful of IITs set up by the Indian government in the wake of Independence.

Nadella’s road is less traveled. He went to Mangalore University, a public university in the Indian state of Karnataka set up decades after Independence, where he studied electrical engineering. Computer science, a discipline he wanted to pursue, was not available at the time but, just as was the case for many Indians of his generation, engineering gave him a gateway to pursue his dream in America.

Anita Raghavan is the author of The Billionaire’s Apprentice: The Rise of the Indian-American Elite and the Fall of the Galleon Hedge Fund.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com