Turn-based science fiction games are scarce in gaming’s history, much less ones with insight into the history of the genre. There’s Julian Gollop’s X-COM (or Jake Solomon’s XCOM, the recent reboot), Brad Wardell’s Galactic Civilizations, Steve Barcia’s Master of Orion and the odd Civilization mod, but the one I’d wager most remember the fondest is Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri from 1999.

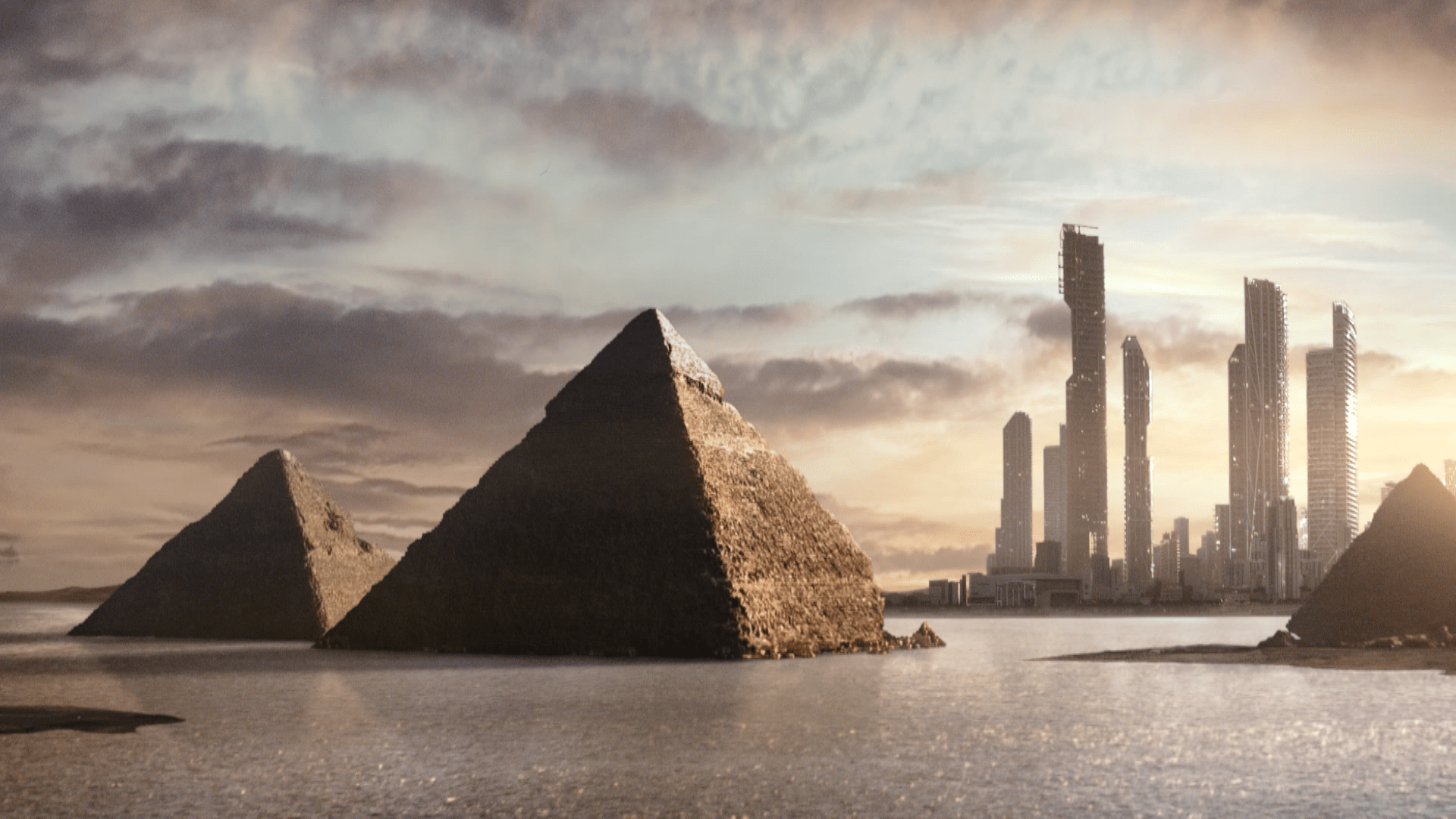

Sid Meier’s Civilization: Beyond Earth is a spiritual sequel to the latter, a 4x (eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, and eXterminate) game that trades its namesake’s traditional obsession with things that’ve already happened for things that have yet to. It’s a game whose design team sounds as intrigued by the ramifications of our post-human future as they are obsessed with folding such heady concepts into a compulsive piece-pusher — something worthy both of the “one more turn” cliche and sci-fi’s legacy of stirring, often subversive fiction.

Firaxis unveiled the game at PAX East on April 12 — it’s due later this year. You can watch the PAX East panel’s announcement here:

This is the second part of a two-part interview, here with the game’s lead designer David McDonough and lead producer Lena Brenk. The first part — with gameplay designer Anton Strenger, Sid Meier’s Civilization series senior producer Dennis Shirk and associate producer Pete Murray — is here.

In Beyond Earth, you lead different factions with contrasting cultures. One of the critiques of Civilization V‘s take on culture was that it felt like a second tech tree instead of a feature unto itself. How does culture work in Beyond Earth?

David McDonough: There’s a system called virtues, which is an expression of what your civilization cares about, so who they grow up to be, what their priorities are and so forth. It’s been totally redesigned for this game, meaning it’s different from any previous Civilization. Culture drives the acquisition of items within a virtue table, and those items have a lot of cross-linking benefits in and out of other systems in the game — everything from city progression to tile improvement to military strategies to territorial acquisition and diplomacy and so on.

Lena Brenk: The way Anton designed it, the trees are a lot deeper, so you have a tree that you can follow down, the whole column through, and the more points you spend in one tree, you get kickers — additional bonuses that you rack up. If you go very wide and select virtues from different branches of different trees, you get kickers as well, but they’re different in that they give you bonuses for going in very different directions and not focusing on one tree. So the system is quite different from prior Civilization games.

Recognizing that realism’s subordinate to gameplay, how hard-science-minded have you been able to keep Beyond Earth, for those who relished that aspect of Reynolds’ Alpha Centauri?

DM: We care deeply about exactly that thing. When we set out to design the game, we were already huge fans of not just science fiction, but actual science, and one of the first things we did, and you can find this on Wikipedia, is that we pulled together the original reading list that the designers of Alpha Centauri assembled. I think between us on the Beyond Earth team, we’d read about half of that list before we got started, so we read the other half, and then some.

Every part of the game’s been designed with a very careful eye toward achieving the sweet spot Alpha Centauri did, with finding a plausible link between science that everybody knows and that’s real, and science fiction that makes sense and comes from it. I think one of the best expressions of this in the game is the technology web. The future is treading technological ground that we don’t know yet, and we get to invent it. So we start you in the center of a web surrounded by technologies that are more or less recognizable, that are based on present-day Earth technologies plus a few hundred years. But then it radiates outward to any of a dozen very different technological places, and they all end up in a very interesting sci-fi place that is definitely sci-fi, but also definitely plausible, and you can see the thread all the way through from today to then and how humankind could have gotten to that technology, and why they would have, and what they’d do with it.

So as you play the game, you get to make these really interesting choices along the way, like what kind of technology is important to me, what fits my needs on the ground, what’s going to help me achieve victory, what do I just find the most attractive, and by the time the game is over, you have a collection that represents your priorities as the human race. Your neighbors on the planet will have made a different set of choices, of course, and you’ll clash because your technologies don’t line up.

LB: I can attest to the enthusiasm with which the design team went at it, and the art team as well. We love history here at Firaxis, we love Civilization of course, but going into the future — far into the future — was really cool. It was a challenge, but such an opportunity for the art team to stretch their legs. The designers came up with the technologies and said this is what we’re going for, and then the art team came in and had to imagine what that would mean for units and leaders and the alien environment, how that would look and be represented in the game. The enthusiasm was incredible, and still is incredible, since we’re only pre-alpha at this point.

What’s the timeframe in the game? How many years are we talking, from launching your colony ship to an average game’s conclusion?

DM: That’s a good question, because we don’t say specifically in the game. And we do that on purpose so the player can enjoy imagining the answers to the questions they’re asking. We hypothesize that it’s roughly 200 to 300 years from today, that that’s when the seeding occurs, and once you land on the planet, you play forward by somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 years.

The reason I ask is that Alpha Centauri managed to sneak in some pretty out-there futurist notions, and if you follow guys like Ray Kurzweil today, you know he thinks this notion that Star Trek‘s going to happen in another century or two misses the point — that we’re going to be clouds of foglets or whatever long before we’d ever get to Roddenberry’s naval-metaphor view of humans sailing through space and yet somehow remain human as we define human today.

DM: Yeah, that was really the first kernel of the design, the first question we asked: What is the human race going to look like in 500 years, let alone 1,500 years? What kind of post-human weirdness is going to happen? There’s no shortage of interesting ideas in sci-fi, ideas that range from plausible to at the same time sort of terrifying.

We sculpted the game around three impressions of that, which we call affinity, and each one represents a concept somewhere between an ideology and a religion — it’s more just a philosophy of what humankind is going to be like by the time you reach the next great turning point in our history.

One of them, supremacy, is very focused on technology as the savior of humanity, that by embracing the machines and eventually integrating them to the point of replacing yourself, the future of humanity is forever assured — that these machines can survive any environment, we will never be displaced from our home again and we’re saved by the machines. Living as a nano-cloud is reflected in the ultimate extent of those technologies in the web and in some of the things you’re able to build, some of the wonders and so on. We go right up to that threshold and hint at it, then suggest to the player, “Look at this crazy place humanity’s arrived at, and just imagine what’ll happen next.”

It sounds like you’re hoping to use the new quest system as your primary storytelling mechanism.

LB: That’s right. In Civilization we’ve generally been able to assume that players know what the history of humanity has been, more or less, to date. You don’t need to be a historian to know who Genghis Khan was, or the Maya. That lets players tell their own story because they have a historical framework to do so.

When we’re going into the future, that framework’s obviously unclear. We still want the player to tell their own story, but giving them that framework was important, and so one of the ways we found to do this was the quest system. We use it to give snippets of information, little insights into the alien planet and the wildlife there, to give the player a feel for where they’ve landed.

You’ve also added a second strategic angle that’s an actual layer physically superimposed above the traditional one. How does the new orbital system relate to the planetary one?

DM: The core experience still transpires on the planet, so think of the orbital layer which exists above it as an augmentation: It’s a different way to play with the same pieces. You build orbital units in your cities, then launch them into orbit, which exists on a camera level above the planet’s surface. All of the orbital units are designed based on their effects on things on the ground (or water, as the case may be). And so everything from terraforming the ground, augmenting your improvements in your cities, buffing your military units or making military tactics possible to the point of outright bombarding holdings on the ground. And then the other way around, with things on the ground being able to shoot down orbital units. That’s how orbital play is done. Whatever your aims and ambitions and problems are on the surface of the planet, the orbital layer is an extension and complication of them.

Sid Meier was one of the lead designers on Alpha Centauri, and Beyond Earth carries his name in the full title. To what extent is that branding? Or put another way, how hands-on is he with Beyond Earth?

DM: Sid is really the benevolent uncle-godfather of all the designers at the studio. Every Civilization game bears his imprint and has his involvement in it. This is no exception. We never questioned that the game would be called Sid Meier’s Civilization. It belongs in the Civilization franchise and we want it to stand along with that incredible legacy.

That said, it’s a brand new experience, and it takes place literally beyond Earth. The title expresses exactly what the game is — that it belongs in the Civilization legacy, but that it’s a new idea within it. And as a designer I can tell you that Sid’s influence, his insight and his participation are extremely important. He’s always present, always willing to play the game and lend his thoughts and perspectives. I think no Civilization game would be made without Sid. He’s the guy.

MORE: The History of Video Game Consoles – Full

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com