The outcry in India’s literary and media circles grew louder this week as the news sank in that Penguin India will recall and pulp all copies of U.S. scholar Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus in India. The publishing giant’s decision — an out-of-court settlement with a group that says the book is offensive to Hindus and therefore in violation of a law criminalizing “malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings” — has raised questions over freedom of expression in India. It’s also highlighted the polarized politics of the world’s largest democracy as it gets ready to stage national elections this spring.

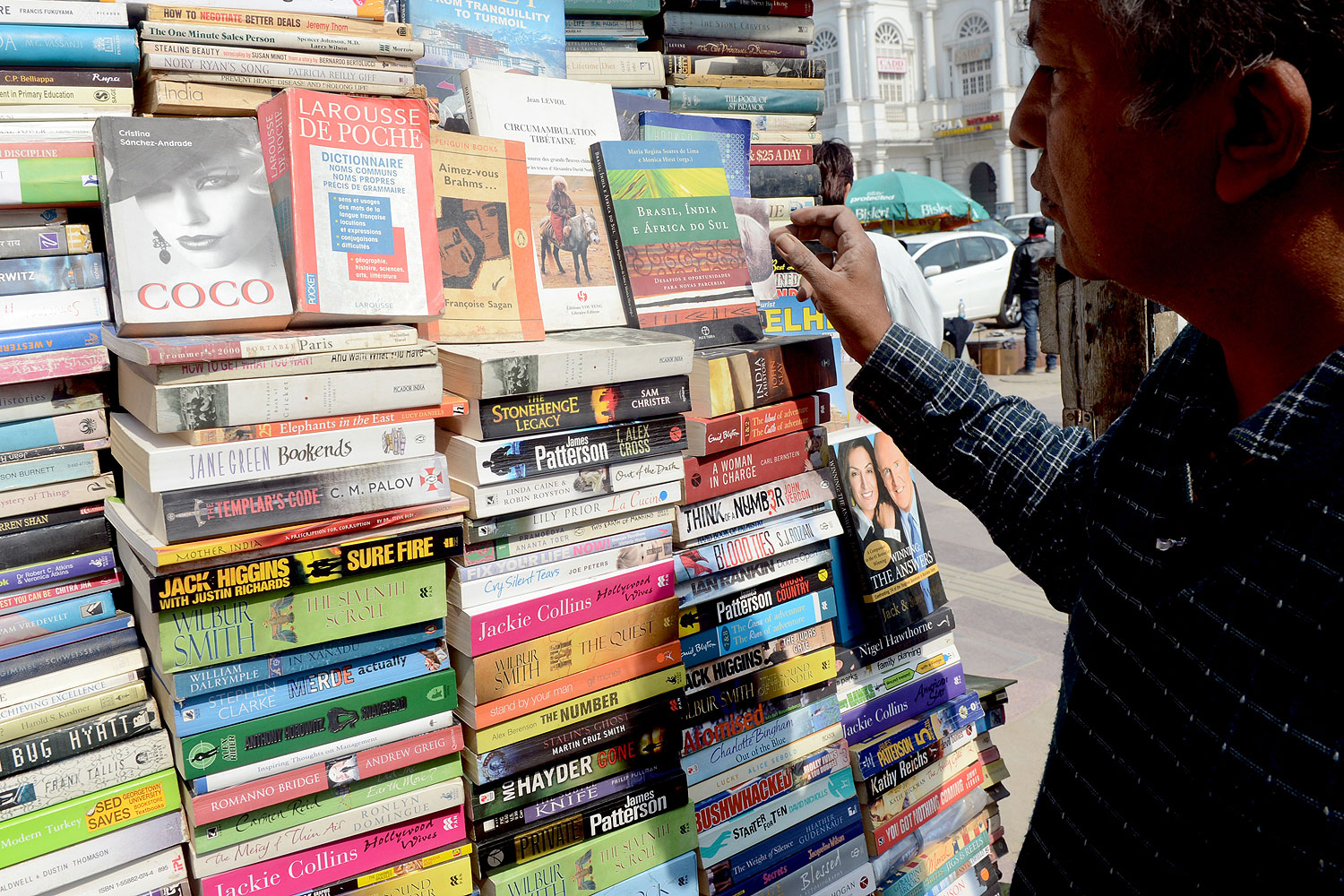

Though New Delhi’s booksellers may have had a banner day on Wednesday as copies of The Hindus: An Alternative History flew off their shelves, the specter of the tome’s disappearance in India has observers concerned. Last month, Bloomsbury India also withdrew copies of the recently published The Descent of Air India by Jitender Bhargava, after a government minister named in the book filed a defamation case against the author and publisher in a Mumbai court.

In a Feb. 12 statement, PEN Delhi listed that and other examples of legal action facing publishers in India. And while the group lamented Penguin India’s decision “to settle the matter out of court, instead of challenging an adverse judgment,” it also acknowledged that the industry is under fire, and said the recall “comes at a time when Indian publishers have faced waves of threats from litigants, vigilante groups and politicians.” (Penguin has not yet released a statement, but Doniger’s can be read here.)

Nikhil Pahwa, a PEN Delhi member and editor of digital-media tracker MediaNama, says the threat of costly litigation has increasingly become an effective way for interest groups to influence publishers in recent years. “Libel chill is the quietest form of attacking freedom of expression, and often the least noticed,” says Pahwa. Ultimately, he says, it leads to self-censorship when editors choose what books to commission, impacting access to knowledge and preventing healthy debate. “I think we should counter words with words,” he says.

(MORE: Sex, Lies and Hinduism: Why a Hindu Activist Targeted Wendy Doniger’s Book)

But the fate of The Hindus also reflects what many say is a deeper problem: the increasing ability of vocal interest groups to take control of the national conversation. Dinanath Batra, president of the Hindu group Shiksha Bachao Andolan that filed lawsuits against Penguin India over Doniger’s book, told TIME that his demands weren’t unusual in a global context. “If someone makes a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad, Muslims are outraged around the world,” Batra said. “So why should anyone write anything against Hinduism and get away with it? It matters because this book is hurting the sentiments of Hindus all over the world.”

Certainly, many agree with Batra. (Some less articulate — and less polite — sentiments against Doniger’s book are being aired under the Twitter hashtag #WendyDoniger.) Batra and other critics of the book have said it is inaccurate and gratuitously oversexualizes aspects of Hinduism. But many also disagree and say activist groups like his are, by exercising their legal right not to be offended, impinging on other Indians’ freedoms. Doniger’s book has not been banned, but other bodies of work have, and the very laws meant to protect India’s religious diversity have had the opposite effect. “Religious extremists have more in common than they’d like to believe,” Indian poet and novelist Jeet Thayil wrote in an email to TIME. “They live to take offense, to intimidate, to threaten. Capitulation is an error. You are asking for more trouble.”

Does The Hindus incident offer any insight into the mood of the country ahead of this spring’s polls? Author Chetan Bhagat cautions against casting the sensitivities expressed by Batra as part of a strengthening Hindu nationalist sentiment, even if it takes place at the same time as the political rise of opposition leader Narendra Modi and his Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. What is happening, he says, is that the country is becoming more polarized as the vote draws near. “There is less respect for fundamental rights. Anybody with a little support group can gang up,” Bhagat says. As a result, a certain liberal sensibility — for people to vociferously object to a book and accept its right to exist — is in retreat. And that makes India look like an intolerant place. “People don’t realize they are harming the image of the country,” Bhagat says, “and the religion they are protecting.”

— With reporting by Nilanjana Bhowmick / New Delhi

MORE: Penguin India to Recall and Destroy Renowned American Scholar’s Book on Hinduism

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com