Extreme weather can be deadly, and the deadliest of all is extreme heat. Approximately 1,220 Americans die every year due to extreme heat, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And more Americans die from heat than any other weather-related hazards—including floods, tornadoes, hurricanes, and cold—per the National Weather Service.

That’s why the CDC and NWS have teamed up to roll out two experimental tools nationwide that will help public health officials and citizens to better prepare for dangerous heat.

“Heat-related illness and death are preventable,” CDC Director Mandy Cohen said when announcing the new HeatRisk initiative.

HeatRisk, which combines public health and historical temperature data to provide an index forecasting the potential impacts of heat on the human body, was conceptualized in 2013 and piloted in California before being expanded to the western U.S. in 2017. As of this week, it can now be used across the country.

Here’s what to know.

How do you use HeatRisk?

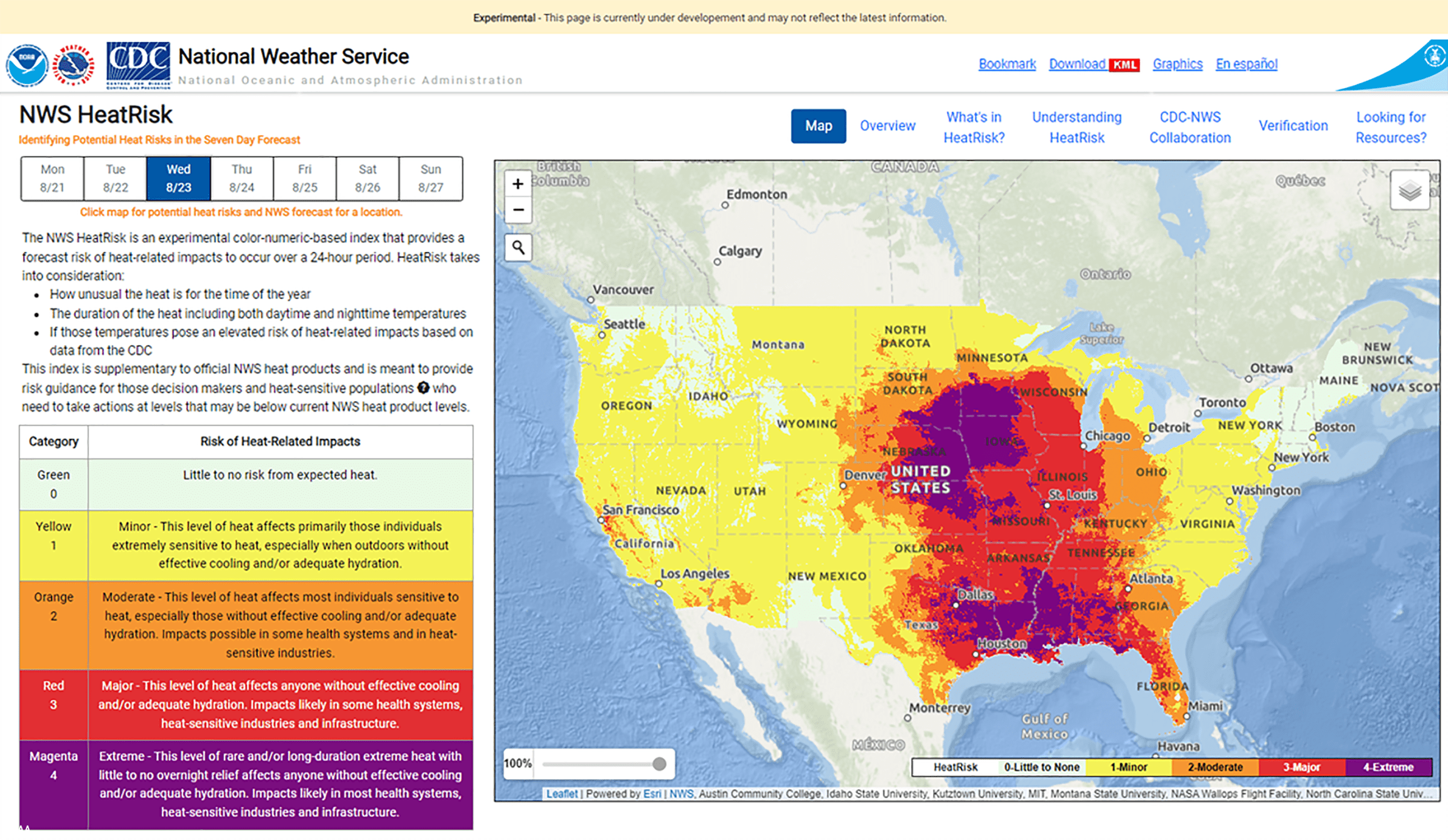

There are two tools to access HeatRisk information: HeatRisk Dashboard and HeatRisk Forecast. The forecast tool is a prototype map hosted by the NWS that provides 7-day heat forecasts to help inform decisionmakers of heat conditions that could be harmful to public health, allowing them to plan responses.

It’s also, at least for now, available to the public while the NWS solicits feedback on the tool. “The NWS HeatRisk forecast is something that can be adapted to your particular needs and heat sensitivity, allowing you to track the forecast and take the actions that you need to take, when you need to take them,” the tool reads.

The HeatRisk Dashboard, which is hosted by the CDC, caters to the general public and pulls data from the forecast map. Users can enter their zip code for easily-digestible and location-specific HeatRisk information. It also provides guidelines and actions individuals can take to respond to the heat.

Who should use HeatRisk tools?

HeatRisk has been used by California schools to decide on the appropriateness of outdoor activity for children, but the new tools can be used by everyone. There are, however, several particularly vulnerable groups to heat—such as the elderly, very young children, people experiencing homelessness, low-income households, those whose jobs are mainly outdoors, and those doing strenuous activities at the height of high temperatures—for which the HeatRisk Dashboard tailors specific clinical guidance.

What exactly does the HeatRisk tool tell you?

HeatRisk has a five-tiered, color-coded index. A tier corresponds to a 24-hour forecast, which considers how unusual the high temperature is, how long the heat would run for, and if those temperatures are associated with elevated risks.

What makes HeatRisk distinct from the other methods of measuring heat is its focus on unusual heat—defined as the warmest 5% of temperatures—specifically for a particular date and location.

There are five heat categories in HeatRisk running from 0-4—the higher the number, the greater the level of heat concern. Magenta (4) is at the extreme high end, which symbolizes the highest risk of heat effects, followed in descending order by red (3), orange (2), yellow (1), and green (0), which represents little or no risk from expected heat. Here’s what each category means and how the HeatRisk tool recommends you act accordingly.

Green (0)

The heat poses no risk, and no preventative measures are necessary.

Yellow (1)

This heat could be tolerated by most, with little risk to groups with heat sensitivity.

Recommendation: Opening windows at night and using fans to cool air inside buildings could mitigate the effects.

Orange (2)

This heat could be tolerated by many, but at risk are visitors to the area who may not have acclimatized to the temperature. Long exposure to the sun could aggravate the effects.

Recommendation: The HeatRisk tool suggests reducing time under the sun. Indoors, those without air-conditioning are advised to use fans and open windows to keep the air moving.

Red (3)

This heat puts most of the population at risk, particularly those who are active under the sun or those who belong to heat-sensitive groups. While largely uncommon across the U.S., it is fairly common in the southern region.

Recommendation: The HeatRisk tool says you should reschedule activities to cooler times of the day, keep hydrated, and use air-conditioning when possible.

Magenta (4)

This is “a rare level of heat” that would persist for days and put the entire population in that area at risk. This level of heat has historically been detected up to a few times a year in southern regions of the country, especially the Desert Southwest. Heat-sensitive groups and those without cooling mechanisms are at risk of dying, and power outages are likely.

Recommendation: The index advises strongly considering canceling outdoor activities, using air-conditioning or gaining access to it, staying in a cool place overnight, and keeping hydrated.

What should you do if you are impacted by heat?

Extreme heat-related illnesses include heat stroke, heat exhaustion, and heat cramps. The CDC’s general advice is to be aware of the warning signs, and to monitor those who are at high risk. Workers out in the heat are also advised to have a buddy with them to monitor their condition, as heat-induced illnesses can impair cognitive abilities. Here’s what to know about the most common illnesses and how to respond to them.

Heat stroke

A heatstroke is a medical emergency that can cause death or permanent disability. Signs of a heatstroke include body temperature that is 106°F or higher, hot or red skin, a fast or strong pulse, headache, dizziness, nausea, loss of consciousness, and confusion. The CDC advises to call 911 right away, to move the person to a cooler place, and to help cool the person’s body temperature as fast as possible. Patients must not be given alcoholic drinks to cool down.

Heat exhaustion

Heat exhaustion can develop over days after continuous exposure to heat. Signs and symptoms include heavy sweating, cold and clammy skin, a fast and weak pulse, nausea or vomiting, muscle cramps, tiredness or weakness, dizziness, headache, or fainting. The CDC advises those with these symptoms to move to a cool place, to change into lighter wear, to cool the body through wet cloth or a bath, and to drink cool non-alcoholic beverages. Urgent medical help is needed for those who are throwing up or those who have prolonged and worsening symptoms, according to the CDC.

Heat cramps

Signs of heat cramps include heavy sweating during exercise and muscle pain or spasms. The CDC advises to stop physical activity immediately, to drink water or a sports drink, and to wait until the cramps go away. Medical help is needed if the cramps last longer than an hour, and if the person has heart problems or is on a low-sodium diet.

Read More: Air Quality Is Bad Pretty Much Everywhere, New World Pollution Report Finds

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com