The International Monetary Fund issued a most unusual rebuttal this month. Its spokeswoman Julie Kozack told reporters in Washington that executive director Krishnamurthy Subramanian’s growth forecast of 8% for India did not represent the views of the IMF, which still maintained a projection of 6.5% for the country.

Subramanian’s views—expressed at an event in New Delhi a few days earlier—were in his role as India’s representative at the IMF, she said. The “executive director” is actually one of the 24 such directors elected by member countries to the IMF’s “executive board,” which, confusingly enough, is “distinct from the work of the IMF staff.” Just how distinct became clear when Subramanian trashed IMF staff on X in response, saying the institution’s GDP forecasts for India are “consistently INACCURATE.”

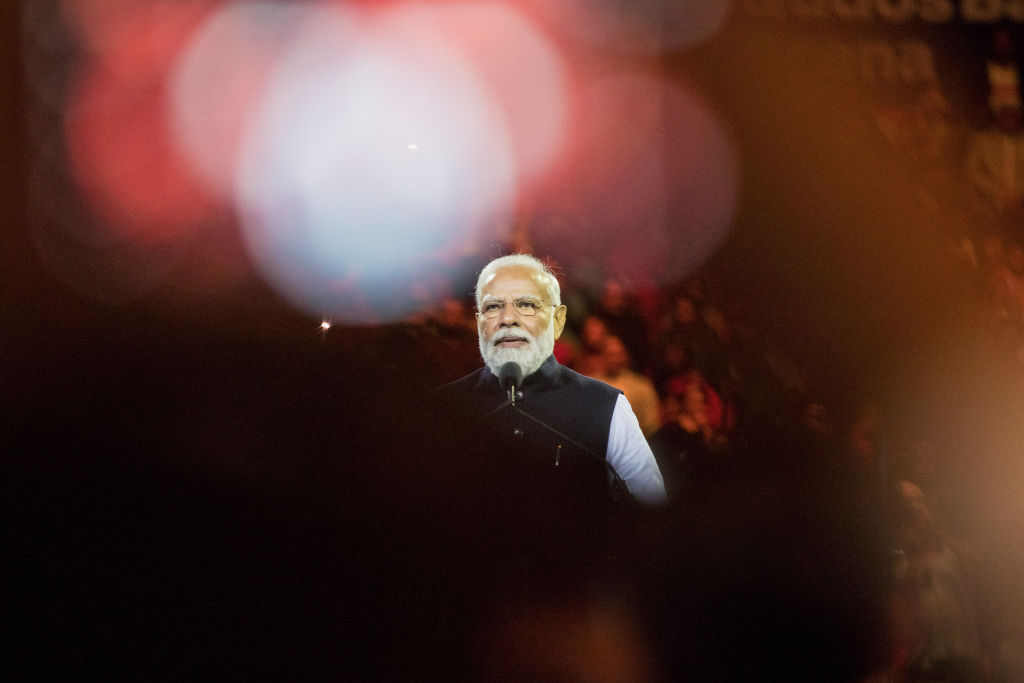

As a former chief economic adviser to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and delegated to the IMF by the Modi government, Subramanian has good reason to take umbrage at the slightest suggestion that India’s economy may not be as robust as thought. The narrative of India as the new economic miracle is foundational to both the personality cult of Modi and the legitimacy of his government at home and abroad.

Modi rode to power in 2014 on the promise of mending a faltering economy. As chief minister of the western state of Gujarat, he had built up a formidable reputation as an efficient business-friendly administrator, which he successfully leveraged in his bid for the nation’s top job. “Achhe din,” or “good times,” was his promise.

Looking at the economic news coming out of India these days, it would seem he has delivered. As the fastest growing major economy, India is considered “the shining star of the global economy,” as the S&P Global Ratings chief economist calls it. It has already surpassed the U.K. to become the world’s fifth largest economy and is expected to overtake Japan and Germany to become the third-largest in five years. The Indian stock market, now the world’s fourth largest, is at an all-time high.

As India goes to polls, data points like these help megaphone Modi’s narrative of the country’s makeover into an economic powerhouse on his watch. At home, they amplify his image as a steady hand on the tiller taking India to ever greater heights. Abroad, they help mute criticism of his Hindu supremacist dispensation’s systematic attacks on India’s secular democracy and its Muslim and Christian minorities.

Read More: India’s Ayodhya Temple Is a Huge Monument to Hindu Supremacy

To be sure, the Indian economy’s size today and the scope of development makes it one of the most interesting growth stories. And, Big Business has much to be thankful for Modi’s reign. There’s less red tape and more administrative focus and push for industry. The government’s policy of incentivizing businesses with subsidies and tax breaks, and helping major homegrown firms to become “national champions” works well for them.

Yet the perception of India’s supposed economic miracle is also a product of a tightly controlled information ecosystem in which data is managed in keeping with the government’s narrative, ably assisted by a regime-friendly media. The simplest statistical fact is that Modi’s second term has actually seen the lowest period of GDP growth since India liberalized its markets in the early 1990s. Per capita income over the past 10 years grew half as fast as the decade under Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh of the opposition Congress Party, while stock market returns are lower than in the previous decade.

Much of the positive changes attributed to Modi, such as digitization of the economy and improved tax collection are a continuation of past trends, policies, and technological advancement. And much of the hype over the overall state of the economy does not wash when you drill down the numbers.

More From TIME

Even Modi’s former economic aides find the recent growth rates of 8% announced by the government “mystifying.” Major discrepancies in the way GDP is being calculated make the data hugely problematic. One of Modi’s former chief economists holds that if correctly measured, India’s economy would actually be found to be decelerating.

Meanwhile, foreign direct investment is plunging. FDI levels are now the lowest in nearly two decades. Even local investors are shying away from opening their wallets. Private capital expenditure remains low. Private sector investment has in fact been falling as a proportion of GDP since 2012 and the economy is now largely driven by huge government investment.

The consumer goods market continues to be sluggish, with people cutting down on staples—emblematic of economic stress. Private consumption growth is the slowest in 20 years, setting aside the pandemic low. Tractor sales, a proxy for the economic health of villages (where 70% of Indians live), have fallen steeply. Banks are battling the worst deposit crunch in two decades as household savings are at a 47-year low while household debt levels are at a record high. Not exactly the signs of a booming economy. In the last financial year, India’s goods exports fell 3% and its crude imports, 14%.

Unemployment is also endemic. The share of young people with secondary or higher education among unemployed youth has almost doubled in 20 years; a third of graduates are unemployed. Jobless Indian youth now pursue opportunities in conflict zones in Israel and Ukraine, and try to smuggle themselves into the West. Indians are currently the third-largest group of undocumented immigrants in the U.S., their numbers having surged faster than those from any other country.

Despite all of Modi’s drumbeating on boosting India’s manufacturing sector with his much-trumpeted “Make in India” campaign, manufacturing’s share of the GDP has fallen. Far from increasing manufacturing jobs, India is losing them in millions. The ranks of farmworkers, meanwhile, have risen by 60 million in the past four years. Agriculture now actually employs a greater share of workers than it did five years ago, a reversal that points to deindustrialization.

There are also concerns about data manipulation. Before the last parliamentary election in 2019, the government buried its own employment data before the election as it showed the unemployment rate to be at a 45-year-high, leading to resignations of members of the National Statistical Commission. A key five-yearly consumer survey result was withheld that year because of “data quality issues.” When it was finally released this February, it showed poverty and inequality has fallen, and consumer spending had tripled in a decade. That contradicts the government’s own findings and data found elsewhere.

By some estimates, around 1 million people referred to as the “octopus class” now control 80% of the country’s wealth and are creating an illusion of national prosperity. The latest “World Inequality Report” calls India a “Billionaire Raj” where income inequality is now worse than under British rule. As the number of India’s ultra-rich has grown 11 times in the last decade, the country has fallen in the Global Hunger Index, and now sits below North Korea and war-torn Sudan. Acknowledging the issue, Modi’s government is giving free grains to 60% of the population.

None of these facts speak to the El Dorado that Modi is claiming to be creating. India needs much more than headline management and upward mobility for a tiny segment to fundamentally transform its economy. Apart from heavy investment in physical infrastructure—which Modi can be duly credited for—his government isn’t doing much else for that transformation.

All Asian economies that have sparkled in the past half-century have seen heavy synchronization between their trade, industrial, and social policies. Land reforms, enormous state intervention in education and health, and other redistributive policies created the bedrock of domestic demand and higher productivity that spurred Asia’s “miracle” countries. These are the reasons why Vietnam, seen as the new Asian miracle, exports more than India with less than a tenth of India’s population. Modi has done little to suggest he has the inclination or the ability for such deep reforms to make India shine. A false gold rush is all he can offer.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com