It’s not something most of us think about, but Amy Kirby has turned the waste that we flush down the toilet into a powerful scientific tool. Human feces and urine contain a plethora of valuable information about the infectious agents we might be harboring, even if they aren’t making us sick.

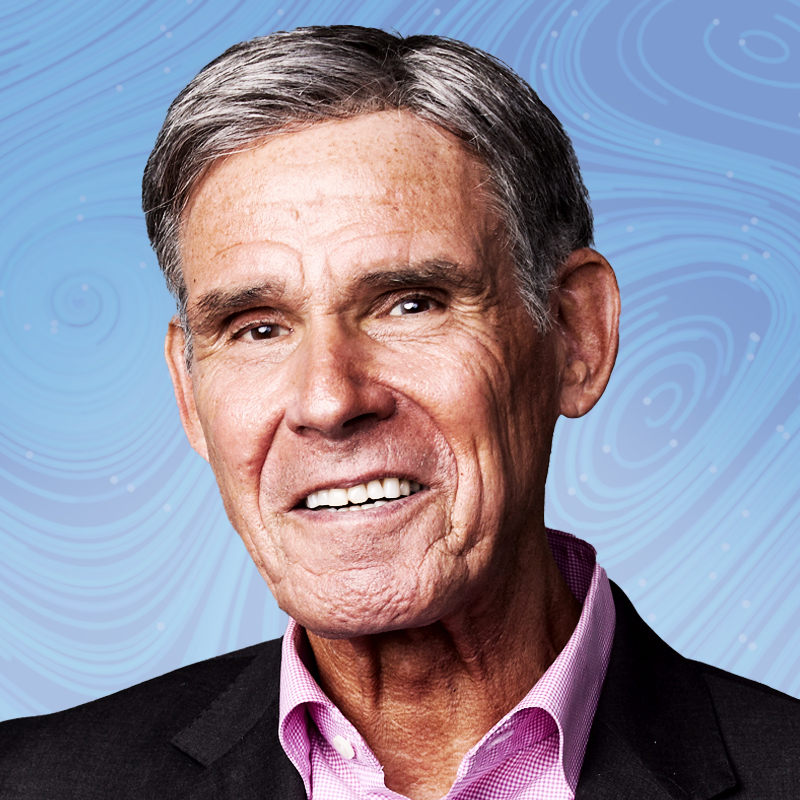

As an environmental microbiologist, Kirby already knew that waste was an untapped research resource, but it wasn’t until COVID-19 hit that her conviction was finally justified. With a grant she received in 2018, Kirby—who now leads the National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWWSS) at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—had been looking for signs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in wastewater and studying whether these bacteria could be transmitted to waste-treatment plant workers. In early 2020 she proposed creating a pilot program at eight sites that would look for SARS-CoV-2. “We didn’t really have a lot of evidence that wastewater surveillance would work broadly,” she says. “And there was nothing at the [CDC] that was routinely collecting and testing wastewater, so we had to build it from scratch.” But by Memorial Day of that year, when people began traveling, congregating, and taking advantage of the warmer weather, “we started to see spikes in every [one of those] communities. That provided great evidence that it was working.”

NWWSS has since grown to include 1,500 sites across the country, and become the early warning system on which the CDC relies to track the ebb and flow of COVID-19 cases. As people moved away from getting COVID-19 testing at doctors’ offices and hospitals to testing themselves at home, wastewater has become the most reliable way of monitoring changes in COVID-19 infections, even as new variants of the virus have emerged. Several studies have confirmed that wastewater can detect increases in COVID-19 days before lab tests at hospitals can. That’s why NWWSS has already expanded to detect influenza, RSV, and mpox. Kirby believes that wastewater can, and should, be a way to not only detect infectious diseases, but help health experts to respond to them as well, by giving health authorities an early warning about where cases are rising so they can better dedicate the proper resources to containing outbreaks.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com