A total solar eclipse will sweep across North America on Monday, April 8, offering a spectacle for tens of millions of people who live in its path and others who will travel to see it.

A solar eclipse occurs during the new moon phase, when the moon passes between Earth and the sun, casting a shadow on Earth and totally or partially blocking our view of the sun. While an average of two solar eclipses happen every year, a particular spot on Earth is only in the path of totality every 375 years on average, Astronomy reported.

“Eclipses themselves aren't rare, it's just eclipses at your house are pretty rare,” John Gianforte, director of the University of New Hampshire Observatory, tells TIME. If you stay in your hometown, you may never spot one, but if you’re willing to travel, you can witness multiple. Gianforte has seen five eclipses and intends to travel to Texas this year, where the weather prospects are better.

One fun part of experiencing an eclipse can be watching the people around you. “They may yell, they scream, they cry, they hug each other, and that’s because it’s such an amazingly beautiful event,” Gianforte, who also serves as an extension associate professor of space science education, notes. “Everyone should see at least one in their life, because they’re just so spectacular. They are emotion-evoking natural events.”

Here are 10 surprising facts about the science behind the phenomenon, what makes 2024’s solar eclipse unique, and what to expect.

The total eclipse starts in the Pacific Ocean and ends in the Atlantic

The darker, inner shadow the moon casts is called the umbra, in which you can see a rarer total eclipse. The outer, lighter second shadow is called the penumbra, under which you will see a partial eclipse visible in more locations.

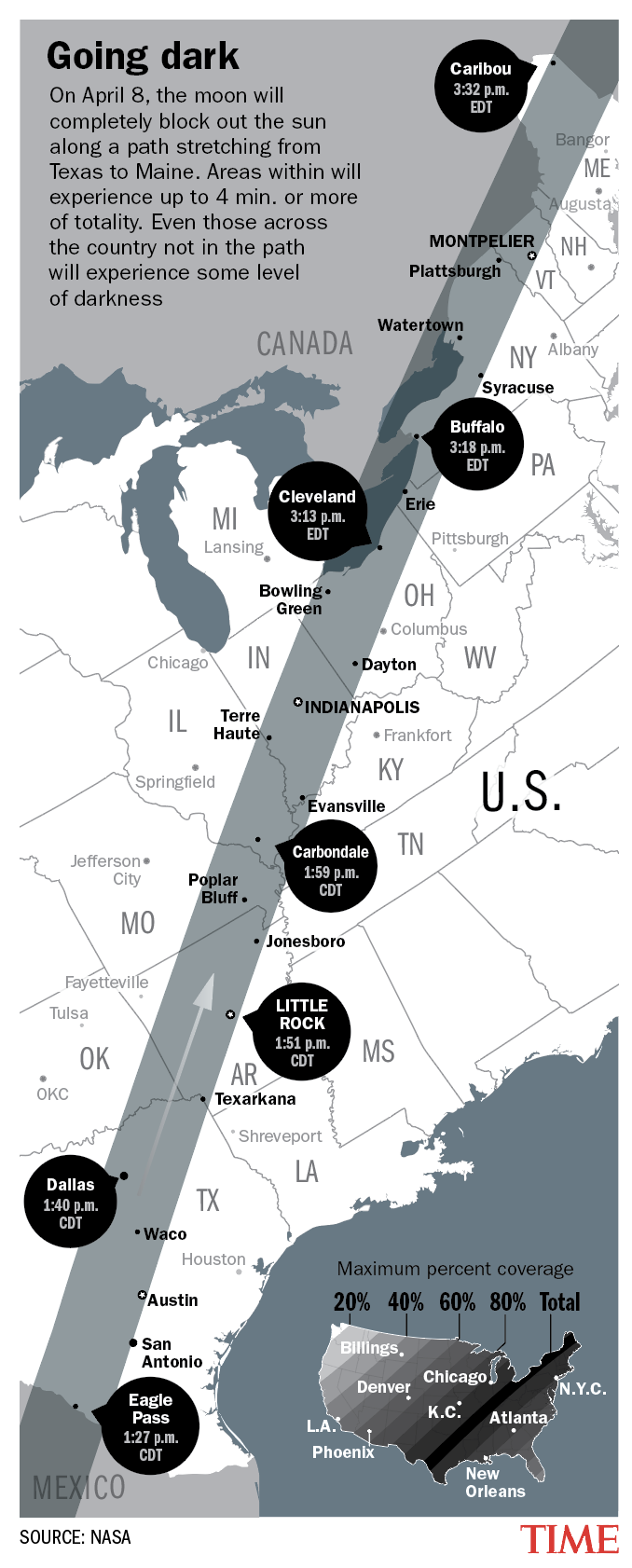

The total eclipse starts at 12:39 p.m. Eastern Time, a bit more than 620 miles south of the Republic of Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean, according to Astronomy. The umbra remains in contact with Earth’s surface for three hours and 16 minutes until 3:55 p.m. when it ends in the Atlantic Ocean, roughly 340 miles southwest of Ireland.

The umbra enters the U.S. at the Mexican border just south of Eagle Pass, Texas, and leaves just north of Houlton, Maine, with one hour and eight minutes between entry and exit, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) tells TIME in an email.

Mexico will see the longest totality during the eclipse

The longest totality will extend for four minutes and 28 seconds on a 350-mile-long swath near the centerline of the eclipse, including west of Torreón, Mexico, according to NASA.

In the U.S., some areas of Texas will catch nearly equally long total eclipses. For example, in Fredericksburg, totality will last four minutes and 23 seconds—and that gets slightly longer if you travel west, the agency tells TIME. Most places along the centerline will see totality lasting between three and a half minutes and four minutes.

More people currently live in the path of totality compared to the last eclipse

An estimated 31.6 million people live in the path of totality for 2024’s solar eclipse, compared to 12 million during the last solar eclipse that crossed the U.S. in 2017, per NASA.

The path of totality is much wider than in 2017, and this year’s eclipse is also passing over more cities and densely populated areas than last time.

A part of the sun which is typically hidden will reveal itself

Solar eclipses allow for a glimpse of the sun’s corona—the outermost atmosphere of the star that is normally not visible to humans because of the sun’s brightness.

The corona consists of wispy, white streamers of plasma—charged gas—that radiate from the sun. The corona is much hotter than the sun's surface—about 1 million degrees Celsius (1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit) compared to 5,500 degrees Celsius (9,940 degrees Fahrenheit).

The sun will be near its more dramatic solar maximum

During the 2024 eclipse, the sun will be near “solar maximum.” This is the most active phase of a roughly 11-year solar cycle, which might lead to more prominent and evident sun activity, Gianforte tells TIME.

“We're in a very active state of the sun, which makes eclipses more exciting, and [means there is] more to look forward to during the total phase of the eclipse,” he explains.

People should look for an extended, active corona with more spikes and maybe some curls in it, keeping an eye out for prominences, pink explosions of plasma that leap off the sun’s surface and are pulled back by the sun’s magnetic field, and streamers coming off the sun.

Streamers “are a beautiful, beautiful shade of pink, and silhouetted against the black, new moon that's passing across the disk of the sun, it makes them stand out very well. So it's really just a beautiful sight to look up at the totally eclipsed sun,” Gianforte says.

Two planets—and maybe a comet—could also be spotted

Venus will be visible 15 degrees west-southwest of the sun 10 minutes before totality, according to Astronomy. Jupiter will also appear 30 degrees to the east-northeast of the sun during totality, or perhaps a few minutes before. Venus is expected to shine more than five times as bright as Jupiter.

Another celestial object that may be visible is Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, about six degrees to the right of Jupiter. Gianforte says the comet, with its distinctive circular cloud of gas and a long tail, has been “really putting on a great show in the sky” ahead of the eclipse.

The eclipse can cause a “360-degree sunset”

A solar eclipse can cause a sunset-like glow in every direction—called a “360-degree sunset”—which you might notice during the 2024 eclipse, NASA said. The effect is caused by light from the sun in areas outside of the path of totality and only lasts as long as totality.

The temperature will drop

When the sun is blocked out, the temperature drops noticeably. During the last total solar eclipse in the U.S. in 2017, the National Weather Service recorded that temperature dropped as much as 10 degrees Fahrenheit. In Carbondale, Ill. for example, the temperature dropped from a peak of 90 degrees Fahrenheit just before totality to 84 degrees during totality.

Wildlife may act differently

When the sky suddenly becomes black as though nighttime, confused “animals, dogs, cats, birds do act very differently,” Gianforte says.

In the 2017 eclipse, scientists tracked that many flying creatures began returning to the ground or other perches up to 50 minutes before totality. Seeking shelter is a natural response to a storm or weather conditions that can prove deadly for small flying creatures, the report said. Then right before totality, a group of flying creatures changed their behavior again—suddenly taking flight before quickly settling back into their perches again.

There will be a long wait for the next total eclipse in the U.S.

The next total eclipse in the U.S. won’t happen until March 30, 2033, when totality will reportedly only cross parts of Alaska. The next eclipse in the 48 contiguous states is expected to occur on Aug. 12, 2044, with parts of Montana and North Dakota experiencing totality.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com