Someone recently asked me why it was important to protect the Amazon rainforest from oil drilling. The question made me angry. Can you imagine being questioned about the importance of protecting your home from being destroyed in a fire? Or about protecting your home, your extended family’s homes, and all your people’s homes from demolition? Can you imagine being asked: Why is it important to protect your country from nuclear devastation?

Those questions seem absurd only when you take the existence of your home and your people for granted. Western civilization has always taken the destruction of my home and my people for granted. And now, this well-meaning question assumes that I must offer a defense of my existence. It also presents a false innocence about the asker’s complicity in the continued destruction of my home.

As a Waorani leader tasked with communicating beyond our territorial borders to safeguard our land, I often face questions like this. Answering is part of the resistance, and it is not easy. Yet, with Ecuador’s government now pushing to ignore our hard-won ban on oil drilling in one of our most biodiverse forests, it remains an urgent question to answer. What I long for, and what the Amazon and Mother Earth demand, can be summed up in what is missing in the questions and policies so often pointed at me and my people: respect.

Why is it important to protect the Amazon rainforest from oil drilling?

We Waorani like to walk. When we need to think, we head off walking in the forest. When we want to express our emotions, we walk and sing: our songs too are fruits of the forest. Wherever we walk, we are in communication with everything around us. We know the plants and the birds in the way city dwellers know the names of streets and the logos of stores. But streets do not breathe and stores do not take flight.

Read More: These Indigenous Women Are Fighting Big Oil—And Winning

The forest is our grocer, our pharmacy, our hardware store, our theater, our gym, our park. We cultivate our small orchards and walk the forest to hunt and to gather food, medicine, tools, and beauty and art supplies. Politicians and oil executives think that we are idiots, that we plod among the trees picking things up that look yummy. They say that we don’t even know the value of the resources beneath the ground. But that is how they show their own ignorance. The oil deep in the earth is the blood of our ancestors. And we know better than to dig up a grave.

Why pillage a grave when life is all around us? We don’t need oil. The forest is life itself. We know which plants can heal and which songs to sing to ask permission for cutting them and using their cures. We know that the petomo palm fruits in January and February and that its oil is excellent for maintaining long, shiny hair and healthy skin. We know that the monkeys and the tapirs time their reproductive cycles to coincide with fruit abundance. We know that the peach palm makes the best spears. We know not to use more than we need.

The first Europeans to enter the Amazon wanted only gold and power. They brought disease and murder. It is no wonder that all their tales of adventure describe the forest as a site of danger. I have had dreams of great dangers to come. Unrestrained industrialization has poisoned the atmosphere. Burning down the Amazon will accelerate climate change beyond a point of no return. Uncontrolled warming will imperil life on earth.

Mother Earth will not be saved. She does not need you or anyone to save her. She demands respect. And she will punish humanity for failing to give it. And yet, time and again, people in positions of governmental and industrial power refuse to do so; they insist on destruction.

They’ve had so many opportunities to respect us, and they’ve squandered them all. Just in recent years, Ecuador’s political class could have upheld Indigenous peoples’ rights to free, prior, and informed consent—the right to decide what happens in their territories, as enshrined in international law by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. But they didn’t. They made us fight. In 2019, my people achieved a historic legal victory protecting a half-million acres of Waorani territory, and setting a legal precedent to protect millions more. The government could have respected that court victory and complied with the ruling, but instead, it has failed to respect it, and continues to have its eye on drilling oil from our lands.

They could have respected our demands to stop all oil drilling and pumping in Yasuní National Park, one of the most biodiverse places in the world, but they didn’t. Again, they made us fight, this time joined by allies across the country. Just last year, the people of Ecuador again made history by voting in a national referendum to stop and permanently ban all oil exploitation in Yasuní. We won. We should be celebrating and coordinating with people in other regions and other countries to help devise strategies to protect their forests. Instead, we are forced to keep fighting: newly elected Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa has called for an illegitimate “moratorium” on complying with the results of the referendum.

Read More: The Fight to Save Ecuador’s Sacred River

Why can’t they respect us? Why can’t they even respect their own laws? How many times do we have to use the tools of the civilization that wants to destroy us, its courts and elections, to stop their destruction? Where is the rule of law when the rulers change the laws whenever they feel inconvenienced? Is it really so much to ask for respect?

I often feel heartbroken when I travel abroad to speak about our struggle. I see how many possessions and luxuries people have and how they only want more. Their greed fuels the burning of the Amazon. Some people on those trips tell me I’m a hero. No, I’m not. I’m just trying to do something. This is resistance.

Why is it important to protect the Amazon from oil exploitation? My life, the lives of my family and people, our homes, our culture, our language, the lives of myriad plant and animal species, many of which are endemic to the Amazon, the life of the forest itself, and the lives of millions of people, perhaps even yours, all depend on it. Is that good enough?

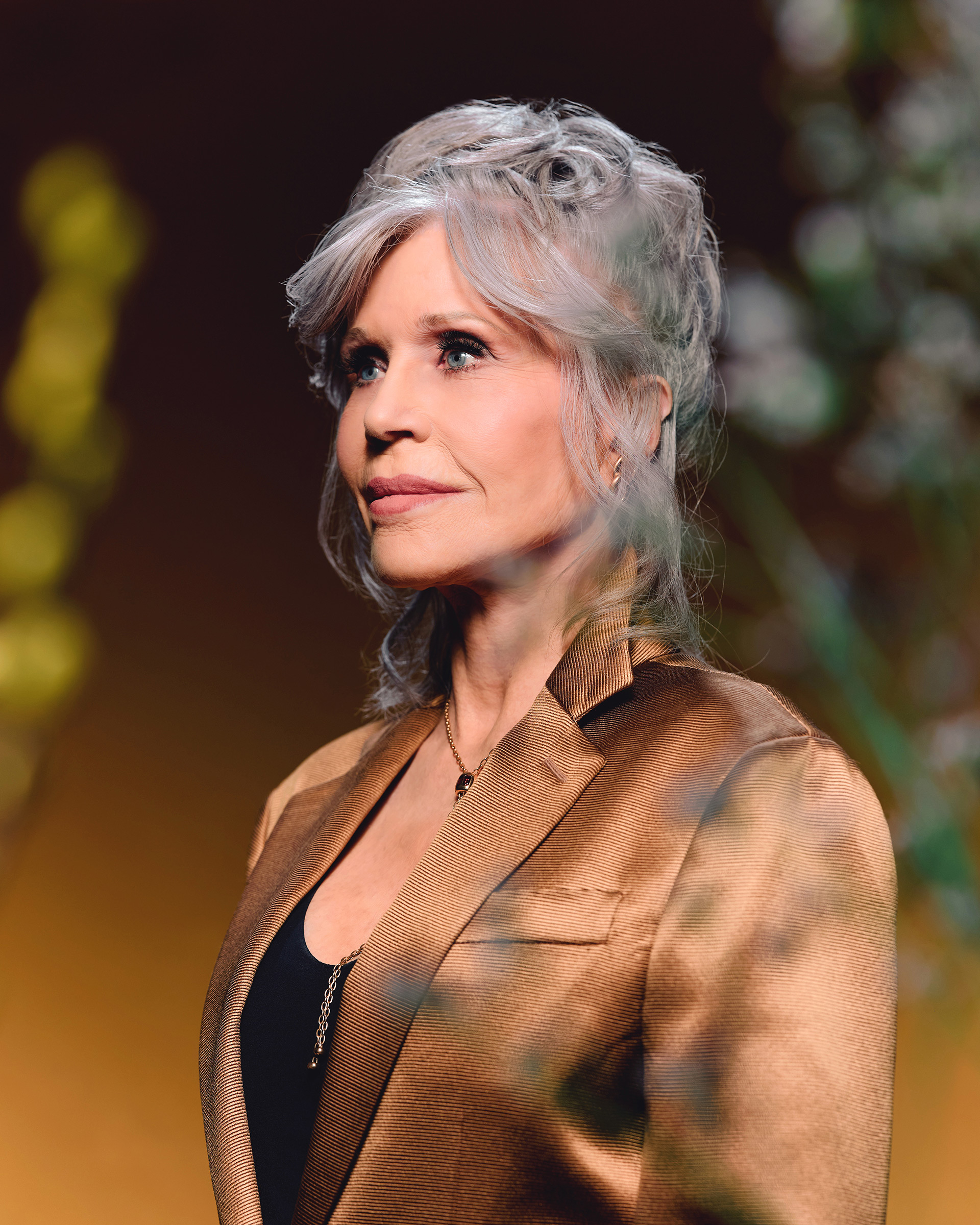

Nenquimo, co-founder of Ceibo Alliance and Amazon Frontlines, is a Waorani leader who has won the Goldman Environmental Prize and a co-author of the upcoming book We Will Be Jaguars with Mitch Anderson

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com