Germans first heard details of the allied landing on D-Day on June 6th, 1944 at 4.50 AM on the armed forces radio station Soldatensender Calais. “The enemy is landing with force from the air and from the sea. The Atlantic Wall is penetrated in several places.” To the first-time listener it sounded like a regular Nazi station, mixing speeches by Hitler and Goebbels with news from the front. But there was a reason for its scoop: it was actually a British station masquerading as a Nazi station, and thus knew about the landings early. The Soldatensender was a very popular covert station: some 41% of German soldiers tuned in, and it was one of the top three stations in major German cities, the equivalent of being one of the top cable networks today. As the fighting raged on, the station gave visceral accounts of German soldiers abandoned by Nazi high command: “They lay in the beach in their smashed and slit up dugouts, naked, without cover. Left behind to be overrun and rubbed out. Who did not know they had been written off—written off from the very beginning.”

Such content was clearly designed to demoralise German troops. But here’s where it gets interesting. The German soldiers and civilians listening to the station knew the Soldatensender was a British station masquerading as a German station. And the British who broadcast the station wanted the Germans to know it was the British. Their aim was not to deceive the listener, but to give ‘cover’ to German listeners. “Cover” so that if the Gestapo or commanding officer caught you listening—you could claim they thought it was a real Nazi station. Cover psychologically: it was easier to hear criticism of German leadership when it was presented as coming from “us” and about “our boys.” And cover to do what deep down many Germans wanted: surrender, defect, shirk and disobey the Nazis.

This intricate psychological game was the invention of Sefton Delmer, a largely forgotten genius of propaganda. As Director of Special Operations at the British Political Warfare Executive, he ran dozens of such covert stations across occupied Europe in many languages, working with a troupe of artists, academics, spies, soldiers, psychiatrists, and forgers. Refugees from Berlin’s cabaret scene acted and wrote the scripts of radio shows. Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, enabled Delmer. Many of Delmer’s most important collaborators were Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany pretending to be Nazis in order to subvert Nazi propaganda from inside, dressing up as their own torturers in order to take revenge. Delmer’s experiences has much to teach us—good and ill—about how to win information wars today. But to appreciate how he came up with a form of propaganda that involved both broadcaster and audience playing such a curious masquerade, we need to understand his past, and what it tells us about propaganda in the first place.

Sefton Delmer was born and spent his first thirteen years in Berlin. His father was an Australian-British professor of Literature at Berlin University. During World War I Delmer was bullied in his German school for being British, an enemy school child. But he also found himself enjoying German war propaganda, singing and marching along to patriotic songs with the other boys. This childhood experience left him with the sense that we have many roles we perform in life. Delmer could be both the pro-German schoolboy, and the British one. All around him he observed Germans performing fervent patriotism one moment, and then showing extreme scepticism of the war the next. Propaganda gives people roles they enjoy performing, that can express and legitimise their most violent and cruel feelings. The question is who is directing these roles, and in whose interests are you playing them: yours, or the propagandists?

When Delmer moved to England he was bullied for being too German—and the wound stuck. Though he eventually learnt to play the perfect English schoolboy, after university he went back to Berlin as a reporter for the tabloid Daily Express. Bilingual, he used his talent for impersonation to pioneer a form of journalism that was part TinTin, part Borat. He would act as a socially inept German tourist in provincial English hotels, speaking with a deep German accent and offending guests with his crass references to World War I, in order to test whether the English would take offense, and investigate whether they had forgiven the Germans for the last war. He even impersonated the assistant of the head of the Storm Troopers, Ernst Rohm, in order to attend a closed Nazi rally. He wined and dined the Nazis in the 1920s, and managed to win them over to such an extent they gave him exclusive access to accompany Hitler on his air tours from one hysterical Nazi rally to the next at the 1928 election.

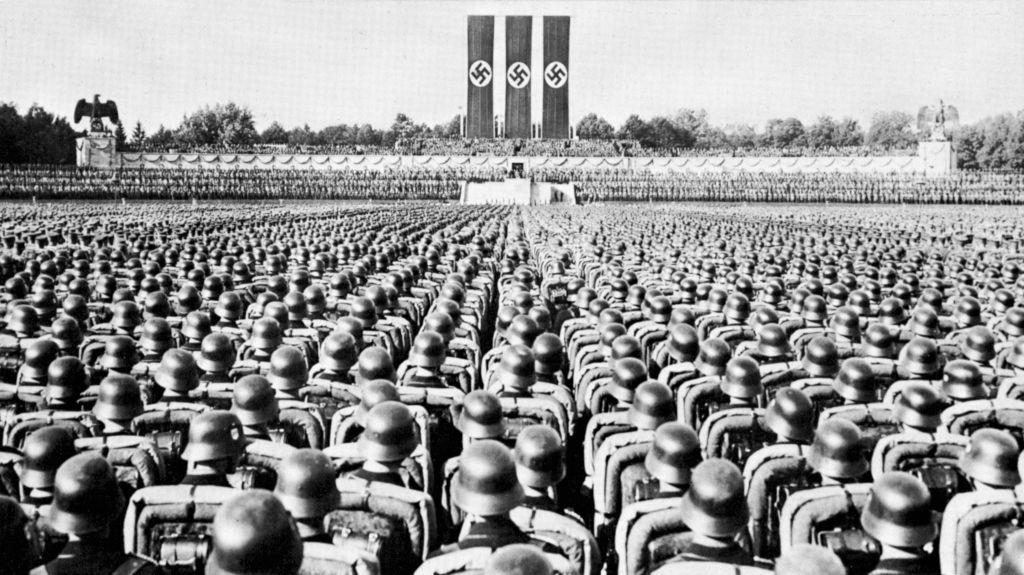

“Sixty thousand Germans are cheering and shouting in hoarse ecstasy while I am telephoning this report from the huge railway station hall here in Nuremberg,” he wrote in a typically breathless report. Delmer saw close up how Hitler, who between mesmeric performances looked like a blank-faced traveling salesman, could rouse the crowd into a near-hypnotic state. The stated aim of Nazi propaganda was for people to abandon their individuality, and meld with the Nazi Volk. ‘Only a mass demonstration can impress upon (a person) the greatness of this community . . . he submits himself to the fascination of what we call mass-suggestion” Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf. “The era of the individual will be replaced by the Community of the People” claimed Goebbels, his propaganda chief.

But at the same time, Delmer observed, Hitler’s followers were also performing their fervour. Delmer described the Nazis as a gruesome cabaret who offered people roles all too many enjoyed playing. In a time of tumultuous social change, where all old identities, including gender ones, were up in the air, the Nazis offered people ways to feel superior and secure in their racial "purity." They offered a role where you could express your hidden sadism, cruelty and anger—all in the name of patriotic "ideals." The figure of the Fuhrer became the vessel through which you could legitimise your most craven urges.

When the Nazis came into power they made Germany into a vast fascist spectacle, with mass marches and endless communal events. The Nazis encouraged people to own cameras, and photo themselves taking part in Nazi celebrations—an early form of selfies. The Nazis built cheap radios, and Germans became the most radio-listening nation in Europe, so now your living room was part of Hitler’s rallies. To counter this propaganda you needed to subvert the emotional bond between the Nazis and the German people, and to undermine the attraction of the roles they cast people to play.

When the war began Delmer gave anti-Nazi talks on the BBC German Service, but he believed the BBC had chosen the wrong strategy. Like many pro-democracy media today the BBC tended to preach to the converted, with noble lectures about liberal values. No Hitler supporter cared about these any more. You can’t win over audiences under the sway of authoritarian propaganda by lecturing them about democracy and decency, or trying to debunk Nazi conspiracy theories. That ignored why people were drawn to the propaganda in the first place. Delmer yearned to try something more subversive and join Britain’s secret propaganda war—but the many roles he had played as a journalist meant he wasn’t immediately trusted by the secret services. Was he a little too German? How close had he got to the Nazis? In 1940, after having finally received security clearance, he got his chance.

In his diary in July 1941, one of Germany’s best known authors, Erich Kästner, noted how many in Berlin were listening to a new pirate radio station on Short Wave: “What it says about the leaders of the Nazi party is mind-blowing.” The station, broadcast by a renegade army officer simply known as ‘Der Chef’, was full of sweary tirades about corruption inside the Nazi party, including graphic porn that depicted the Gestapo and SS indulging in decadent orgies and pestering soldiers’ wives while heir husbands suffered on the front. “The shit Gestapo is sleeping in the day and drinking in excess and fornicating in the night together with the spies and saboteurs,” Der Chef ranted. The broadcasts were full of tirades about Yankee-swine, stink-Japs, Russian pig–Bolsheviks, and Italian lemon-faces. He called Churchill a “dirty, Jew-loving drunk.”

The sex and swearing were strategic. Der Chef used the cliches of Nazi propaganda—but turned them against the Nazis. He accused Nazi officials of being secret Bolsheviks, of plotting against the German people, of being too weak. A British intelligence source in Sweden reported that the station “destroys in the German people their confidence in the Party apparatus... The organiser of the station must be in touch with the German army and in touch with oppositional Army circles. One must say confidently this station is the most listened to in the whole of Germany.” A source inside the German propaganda Ministry advised the British intelligence to recruit ‘Der Chef’—unaware he was a British creation all along.

Der Chef was Delmer’s first show in his cabaret of counter-propaganda. No soldier, he was actually played by a mild-mannered, exiled German-Jewish novelist. He was as far from the prim moralism of the BBC as could be imagined. The aim of the shows, Delmer explained when presenting his programs to the King of England was to “push Nazi propaganda into the ridiculous.” This wasn’t the same as satire—in these early shows Delmer still wanted Germans to think this was a genuine soldier. Instead Delmer took the foul, racist language of Nazism, exaggerated it and turned it against the Nazis. By accusing the Nazis themselves of being secret Bolsheviks, for example, Delmer was pushing Nazi propaganda lines to the point where they undermined themselves.

Moreover, by distorting and flipping the propaganda, he was making people conscious of how fabricated this language, and the roles it bequeathed people. The Nazis wanted people to fully inhabit the roles they invented for people—that of Aryans or Volksgenosse. Delmer wanted to drive a psychological wedge between them.

What Delmer seems to have been looking to provoke is that strange moment of alienation from oneself when you become suddenly aware of how full of artifice and performance your own behaviour is. We saw another, accidental, variation of this effect in the talk by Alabama Senator Katie Britt when rebutting President Biden’s State of the Union address. Britt wasn’t trying to be satirical, but by slightly overacting her speech, she made even people loyal to the MAGA movement aware of just how full of cliché and forced poses this propaganda is.

Delmer then further undermined the pleasures of the Nazi performance. The Nazis portrayed Germans as strong and clean—people were meant to enjoy associating themselves with this image of ‘pure’ Germans. Meanwhile the Nazis shoved all imagery of disease onto their victims, depicting Jews as vermin and maggots. Delmer wanted to cover the Nazis “with a layer of filth as thick as they had spread onto jews.” Der Chef depicted Germans ravaged by disease, lice and malnutrition—all brought on by the Nazis, thus associating them as a source of sickness.

Delmer’s aim was for people to stop reveling in the roles Nazis bequeathed them—and instead start acting in their own self-interest instead. The stories of corruption among officials, of how they took the best food and shirked military service, were to give people the excuse they needed to do these things themselves. Delmer didn’t think propaganda so much persuaded as legitimised what people wanted to do deep down. Nazi propaganda legitimised cruelty, gave people an escape from personal responsibility, and allowed a strongman leader to solve things for them. The catch was you ended up acting in their interests. What if you could act in your own instead?

These early shows had one big problem because Der Chef was hiding his provenance, he was swiftly unmasked. In less than a year the Nazis worked out the British were behind Der Chef, and embarrassed the British on the topic in their own media. This was ironic as the Nazis were also trying something similar themselves.

Goebbels had created a series of stations that pretended to be British and all advocating to capitulate to Germany. One, for example, aimed at British workers and claimed, “The so-called bosses of ours are all swine who’ve taken a Yid bribe. This movement is British. Come out into the streets and put it into action! Workers of Britain unite—you have nothing to lose but your chains!” These shows, which were nothing as popular as Delmer’s in Germany, were also quickly caught out by the British.

So Delmer decided on a new strategy. Instead of a pirate station on Short Wave like Der Chef, he broadcast his biggest media, the Soldatensender, on Medium Wave, where only states had the power to broadcast: the equivalent of having a network in your cable package rather than watching a YouTube show. This way Germans would know the station was really British, but would have the cover necessary to stay physically and psychologically safe. Delmer was creating a masquerade where it was safe to reveal the truth. His shows were full of incredible detail about life on the front provided by partisan groups in occupied Europe; interrogations of POWs; opening the letters of Nazi officials and many more sources. Not only did this drive up audience figures, it also gave even more of an excuse to act against Nazi orders. If the British knew so much about their conditions anyway, what was the point of resisting?

And there is something in the very act of listening to such a station that stimulates people to think and act more independently. If the Nazis wanted you to give up your individuality, become a limb in the great fascist show—here the opposite process was happening. Here was a media that just by the process of tuning in required you to make a series of autonomous, conscious steps to engage with it. You put on a series of disguises to listen to the Sender, but in that very process you were both active and self-aware. The contorted mental gymnastics that people went through when tuning in to the Sender had them bend their minds out of the passive mental state that Goebbels wanted.

Delmer was always fascinated by how we perform ourselves. The choice we have is to play the roles defined by the propagandists, and in their interests, or to take control and be actor-directors of ourselves.

Did it work? Delmer tended to avoid answering directly. He would say that propaganda can only help the more important military and economic policies, and his aim was to generally corrode Nazi morale and cohesion. It is true that soldiers and civilians were far more ready to surrender on the Western front, the target of Delmer’s media, than on the Eastern—but there were many reasons for that, not least the fear of Soviet atrocities. We do know from British surveys of German POWs that almost half listened to the Sender—a remarkable figure—and many said they were grateful for the ‘cover’ the stations gave them. Imagine we could get 41% of Russian soldiers to tune into something Ukraine and its allies created today! And in a time when we lament how hard it is to break through polarisation and ‘echo chambers’ in democracies, Delmer showed you could get engagement, and trust, from audiences who were on the other side of a real, and not just a culture, war.

There are also cases in the British and other archives of German soldiers surrendering after listening to shows on the Sender. One submarine commander, according to a memoir by an OSS agent, gave up his boat after Delmer’s Sender had broadcast a song to congratulate him on having a child when he hadn't been home for two years. More reliably, interviews with POWs from original archives show them telling the British that the Sender did indeed give them cover, and encouraged them to surrender as the British seemed to know so much about the details of their every manoeuvre.

An even more niche evidence of success was related to Delmer by Otto John, one of the few survivors of the Valkyrie plot by members of the German military to assassinate Hitler and stage a coup. The leaders of the coup, John said, thought that if the British were creating stations that encouraged a split between the Nazi party and the military, London would support their plot. Hans Fritszhe, the head of Nazi radio, also told Delmer at Nuremberg that Hitler’s closest confidantes were so alarmed at the level of detail about German politics in the Soldatensender, they were convinced one of their own was leaking secrets to Delmer. This lead to officials being herded in for interrogations. And finally there is the evidence of Goebbels and his propaganda minions, who were often complaining of Delmer, and tried to debunk his shows in their media. The head of the SS in Munich lamented how the Soldatensender was one of the top three stations in the city. But when censors tried to jam it, they ended up drowning out official Nazi stations too and had to stop.

The lessons from Delmer today are positive, negative—and urgent. His disinformation had parlous effects. After the war Delmer worried that fostering the image of ‘anti-Nazi soldiers’ allowed real Nazis sympathisers from the miliary top brass to re-integrate into positions of power. But it was the truths that Delmer penetrated beneath the lies that are still valuable. His ability to engage audiences that seemed lost. His understanding of the power of propaganda as legitimising the nastiest feelings, and about giving people pleasurable roles to perform in a confusing world, are apposite in an age of social media. Online we are all constantly presenting versions of ourselves.

Today you don’t need to go to a physical rally to join a communal performance—online algorithms encourage people to pile into a loud angry crowd, all sharing the same phrases, emoticons and spinning into a seething snowball of superiority and fury. While the Nazis were uniquely nasty, underlying patterns in propaganda persist. Propagandists across the world play on the same emotional notes like well-worn scales. They legitimize people’s secret desires to be the horrible people we wouldn’t usually dare to be. They give a sense of false community to those left feeling deracinated by rapid change; peddle a sense of pure identity through which to project our worst feelings about ourselves on others; foster the same sense that you are surrounded by hidden enemies that want to take something from you, something that’s yours and only yours and only you deserve; and play into the yearning for a strong father figure to protect you. At their most effective they can construct whole alternative realities, conspiratorial worlds where you have no responsibility. And many people can be eager to play along with this.

Our world is full of Goebbelses great and small. Do we have any Delmers to compete?

Adapted from Peter Pomerantsev's How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler, just published by Public Affairs

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com